Bots, Lies, and DeepFakes — Online Misinformation and AI's Role in it

Information warfare online is serious. AI is just one part of the problem — and solution

Image credit: Unbabel

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Misinformation (misinfo) is “incorrect or misleading information,” and disinformation (disinfo) is a subset of that which is “deliberately and often covertly spread… in order to influence public opinion or obscure the truth.”

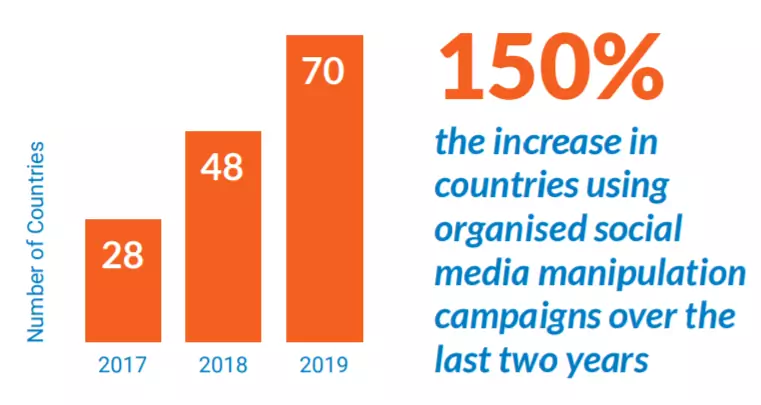

- Because it’s optimized to catch people’s attention, misinfo spreads more quickly than true information; the Internet allows this process to speed up even further. As misinfo spreads, it erodes trust in communications, media, and society, thus posing great dangers to democracies. Every year, more countries are found running disinfo campaigns online, with 70 countries found doing so in 2019.

- Though many people fear sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI)’s potential role in exacerbating misinfo, bad actors are not using cutting-edge technologies to spread misinfo. Instead, they prefer paying people to write false content and exploiting the recommendation systems of social media in order to reach their target audience, relying on readers’ knee-jerk reactions to spread their messages further.

- Dozens of organizations are already taking various approaches to fight the spread of misinfo and actively building a stronger information ecosystem. On an individual level, it’s best to develop stronger critical thinking and mindful media consumption habits to avoid worsening the spread of misinfo online.

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, the term “fake news” has lost its bite through overuse since the 2016 presidential election. Though misinformation is not a new phenomenon, its impact and spread has been particularly severe in the last decade as trolls, malicious actors, and state-sponsored media groups exploit the new affordances of social media and the Internet. Everyone — authority figures, journalists, everyday citizens — is a potential target. In its 2020 Doomsday Clock Statement, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists states that the greatest dangers to humanity “are compounded by a threat multiplier, cyber-enabled information warfare, that undercuts society’s ability to respond.”

Artificial intelligence (AI) can — and does — play a nontrivial role in the spread of misinformation. When Pew Research canvassed 979 scientific experts on artificial intelligence in 2018, one common theme was that AI could allow increased “mayhem” or “further erosion of traditional sociopolitical structures and the possibility of great loss of lives,” partially due to “the use of weaponized information, lies and propaganda to dangerously destabilize human groups.”

Despite global consequences, online misinformation continues to live in a cloud of relative obscurity, and AI’s role in exacerbating the problem is particularly misunderstood. With this article, I hope to help readers consider the state and severity of online misinformation, as well as understand AI’s role in this.

DEFINITIONS

To talk about AI’s potential role in the spread of misinfo online, we need a solid understanding of what “misinformation” and its child “disinformation” mean.

Misinformation (misinfo) is “incorrect or misleading information.” Misinfo is not necessarily misleading on purpose; it could be the result of improper communication, incomplete information on the source’s part, or any number of reasons.

Disinformation (disinfo) is a subset of misinfo. It is “false information deliberately and often covertly spread (as by the planting of rumors) in order to influence public opinion or obscure the truth.” False means “not genuine; intentionally untrue; adjusted or made so as to deceive; intended or tending to mislead”; in other words, disinfo can be any mix of fabricated information and true information taken out of context.

WHY WE SHOULD CARE

News outlets or your friends and family may have informed you that “fake news” is vaguely dangerous. But why, exactly, is it important to learn about disinfo campaigns and the spread of misinfo online? And to what extent is it affecting you?

EXPOSURE TO MISINFO IS UP; PROTECTIONS AGAINST IT ARE DOWN

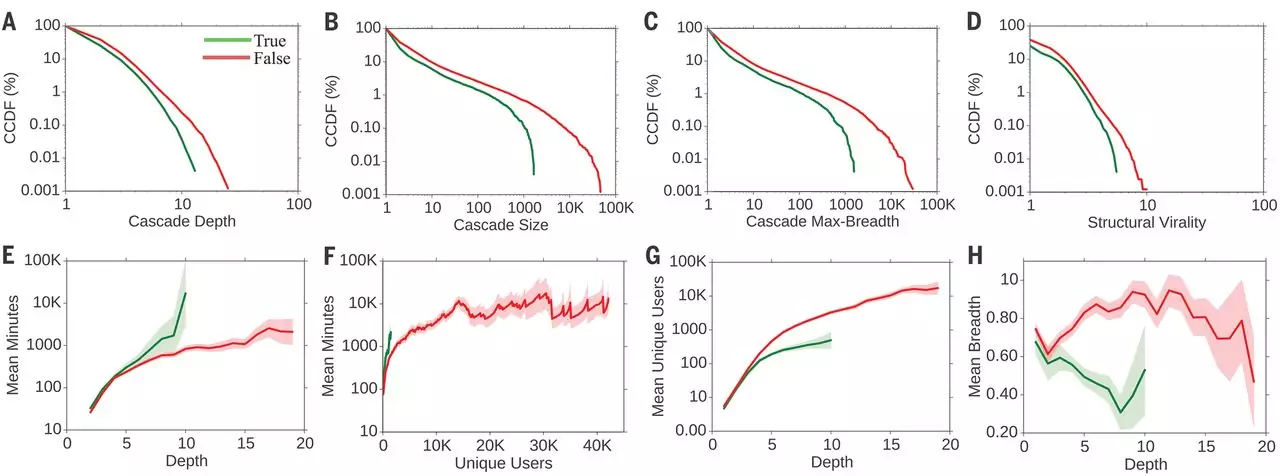

As of November 2018, television is still the most popular source of news for most Americans — but a nearly equal number of Americans now get news online. And at least on social media, misinformation spreads further and deeper than true information.

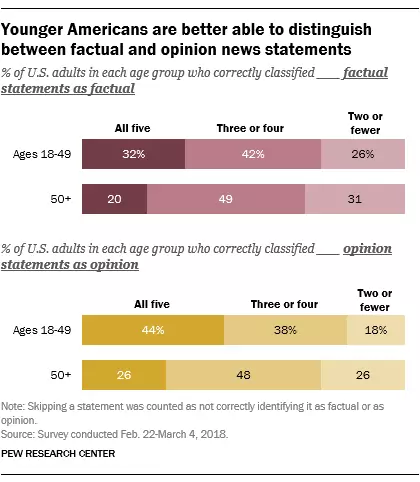

Some groups of people may be more susceptible to online fake news than others. Seniors (age 65+) don’t go online as much as younger folks, but ”[once they] join the online world, digital technology often becomes an integral part of their daily lives” and they’re not prepared to navigate the online infosphere. 1

However, people raised in the digital era are not experts at navigating the online infosphere either: most students in middle school, high school, and college do not have the ability to identify and be skeptical of sponsored content, uncited images, or advocacy-organization-backed tweets. Furthermore, many young Americans (ages 18-29) get their news online, so they are more likely to be exposed to content by unknown and unvetted sources. 2

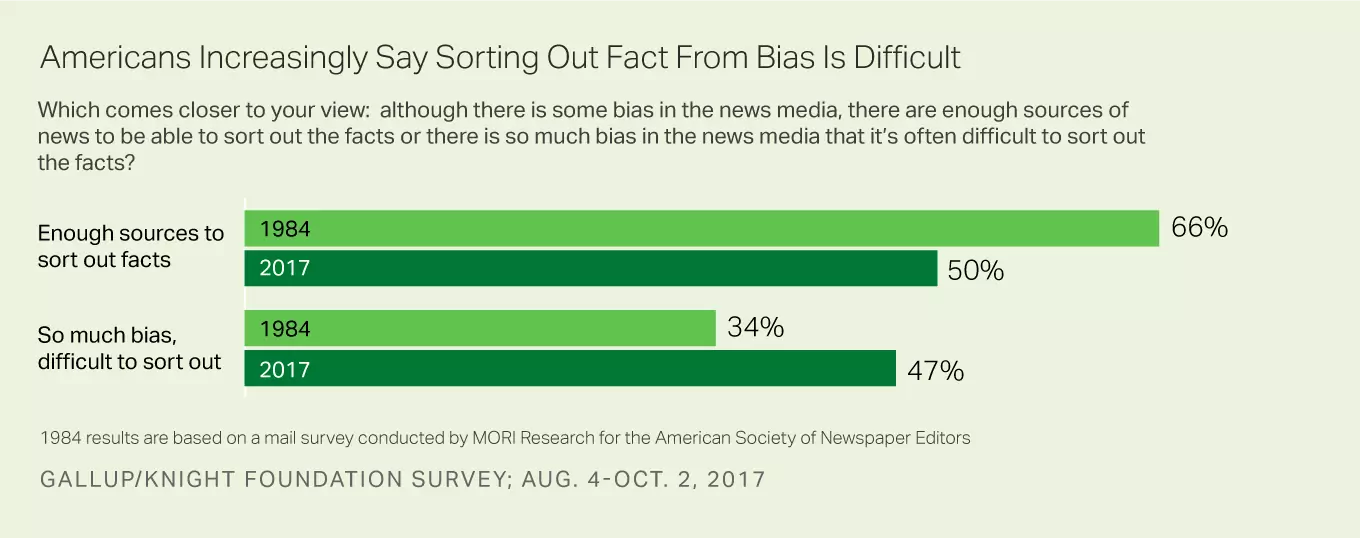

Even people primed to be skeptical of varying news sources are having a difficult time figuring out the truth. In a 2017 Gallup poll, though Americans are more skeptical of news sources than ever, 58% found it “harder to be well-informed,” and less Americans believed that there were “enough sources to sort out facts.”

MISINFO LOWERS OVERALL TRUST IN NEWS

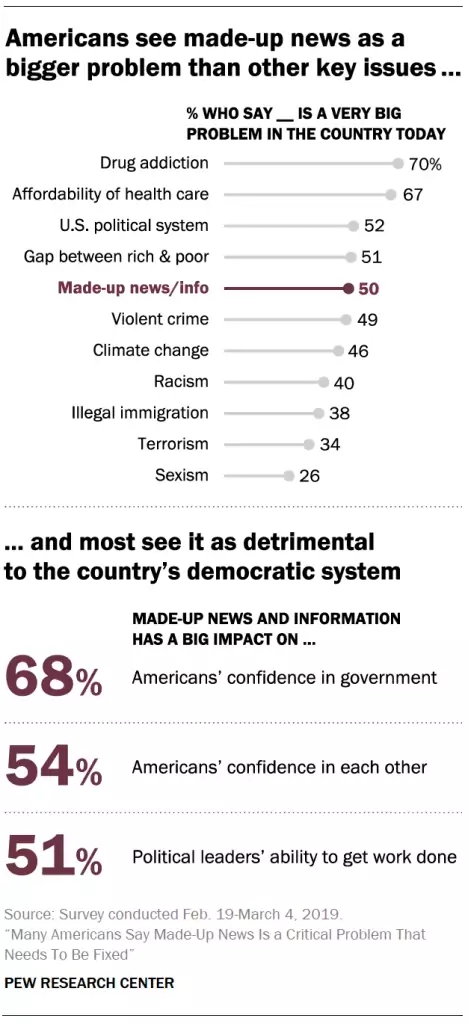

Misinfo not only impacts how people approach something, but (if uncovered) fundamentally shakes people’s faith in the news (Wired). According to Pew Research, “nearly seven-in-ten U.S. adults (68%) say made-up news and information greatly impacts Americans’ confidence in government institutions, and roughly half (54%) say it is having a major impact on our confidence in each other.”

MISINFO IS AFFECTING PEOPLE GLOBALLY

Looking globally, the effects of misinformation may be amplified in places that are newer to the digital infosphere or are highly nationalist. India is both: BBC reports that at least 24 people in India were killed during 2018 “in incidents involving rumours spread on social media or messaging apps,” primarily WhatsApp, where many “false rumours warn[ed] people that there [were] child abductors in their towns, driving locals to target innocent men [unknown] to the community.” 3

On a larger scale, University of Oxford researchers report that in “26 countries, computational propaganda is being used as a tool of information control in three distinct ways: to suppress fundamental human rights, discredit political opponents, and drown out dissenting opinions.” Furthermore, there is evidence of “organized social media manipulation campaigns which have taken place in 70 countries.”

MISINFO HAS MEASURABLE CONSEQUENCES ACROSS FIELDS

The Internet makes it easier to spread and access information. This characteristic means misinformation online has an amplified impact on many things, which I’ve provided examples for below.

Natural Disasters

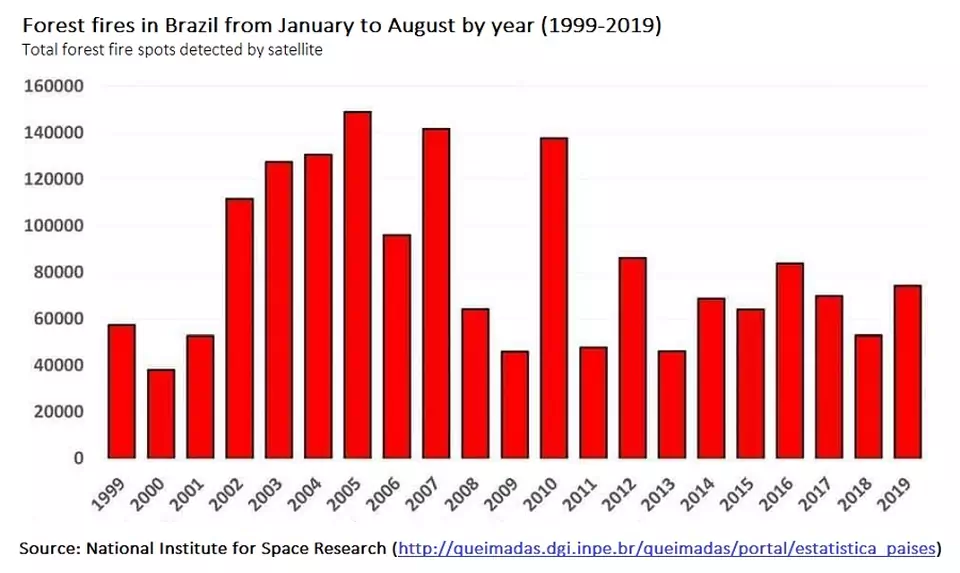

Citizen information and misinfo both helped and harmed in significant ways during Hurricane Sandy, the ebola outbreaks panic, and the Japan tsunami of 2011. In recent events, celebrities and folks drumming up support for the 2019 Amazon fires accidentally shared calls to action on social media alongside pictures of Californian wildfires, and furthermore exaggerated the severity of the situation with regards to its forecasted impact on the environment.

Human Rights

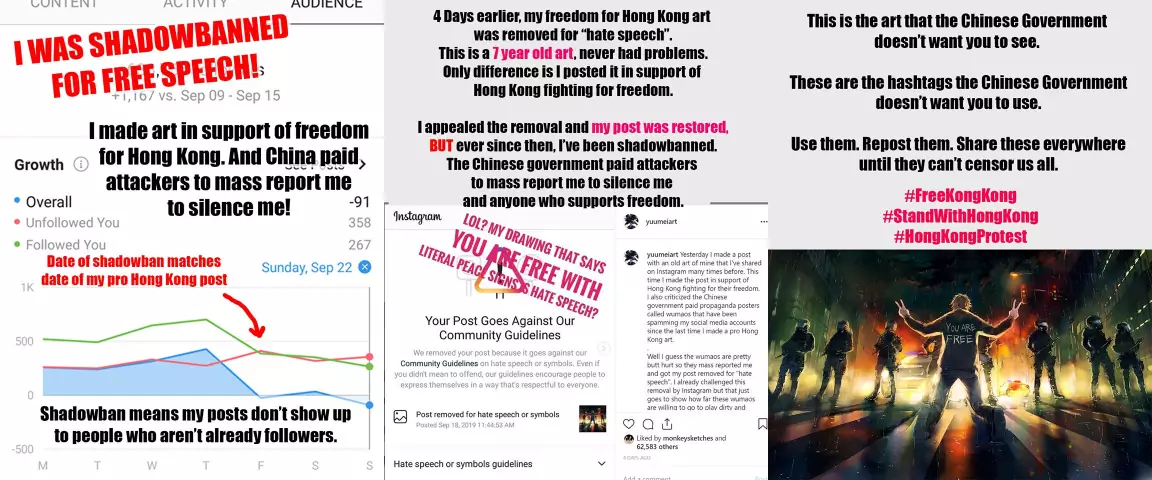

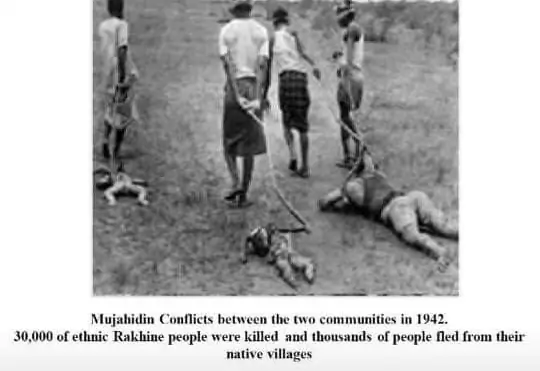

Misinfo “has the potential to trigger new violence and abuses in fragile communities and exaggerate existing tensions” (Koettl). Take the 2019 Hong Kong protests, which were escalated by China’s state-run disinformation campaign. Or the long-going and painful Israeli-Palestinian conflict, where UN members stated in 2018 “that the media can be a part of the solution as much as the problem,” and that “journalism [at least around this conflict] appears at times locked into irreconcilable narratives, hurting its own credibility.”

Politics

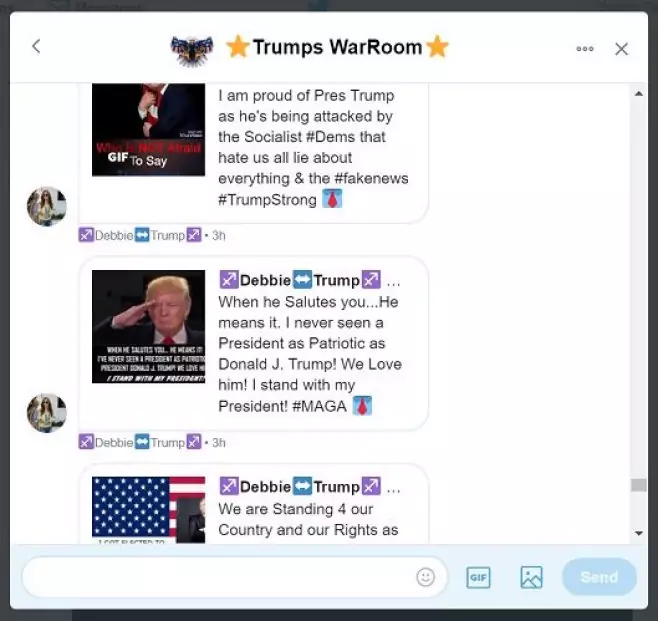

Just pre-2016, clickbait websites based in Macedonia and San Francisco were created to mislead people about the 2016 U.S. presidential elections. Regular citizens learned how to gain ideological traction online by coordinating with like-minded individuals to make digital political movements take up more attention online. The Institute for the Future released eight case studies on social and issue-oriented groups in the U.S. conducted during the 2018 midterm elections, which illustrated how disinfo campaigns attempt to shift public policy by targeting and splintering vulnerable groups. When the Alabama and Georgia abortion laws were hotly debated online mid-2019, liberals and conservatives alike misinterpreted the laws in context and responded with either panic or misinformed support.

As these machinations play out, American youth’s trust in institutions are significantly lower than their parents’ and grandparents’ (Pew).

Science, Technology, + Development

Funnily enough, there is plenty of misinformation about technologies which are capable of propagating misinfo, and people who are afraid of the consequences of new tech lobby to shut down tech development. Anti-vaccine sentiments spread as concerned citizens continue to believe the (already retracted) single work purportedly showing a tie between “autism and the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine,” which has served to bring measles back from the brink of extinction and line the pockets of the original author. People continue to fight against basic scientific consensuses, partially because thinkers from the George C Marshall Institute (a major conservative think tank, now integrated into the CO2 Coalition) back in the 1980’s launched a concentrated, economically-motivated campaign against “cigarettes being harmful to humans” and “climate change being real.” 4 And these only scrape the surface of what’s out there.

HOW IT WORKS

The state of misinformation affects outcomes in the real world. So how does it work, and how is it exploited?

MISINFO APPEARS IN MANY FORMS

There are a few different kinds of form factors that misinformation can appear in. Paraphrasing this article by the Columbia Journalism Review (2016), we have the following type breakdown (ordered loosely by increasing intent to mislead):

- Parody content, created for the purpose of satire but can mislead people if they do not understand the creator’s intent.

- Authentic material used in the wrong context, which could’ve been put in the wrong context for any number of reasons, but ends up misinforming people.

- Fake information,” which could’ve been a result of the creator’s misunderstanding of the information they accessed and reporting it improperly, the creator themselves having been exposed to misinformation and reporting it in good faith, or the creator deliberately making false information (see example tweet below).

- Manipulated photos, videos, or audio, which is used as an artifact to support an otherwise baseless argument.

- Imposter news sites, designed to look like brands we already know, usually tries to take advantage of brand recognition to get more traffic.

- Fake news sites, which are committed to creating news that supports a particular agenda, though they often post real content on non-divisive issues to increase credibility (ex. RT, previously Russia Today, and Sputnik, the propaganda wing of the Russian government).

Certainly, types of disinformation are not easy to distinguish from each other—to its own benefit. As a Myanmar disinformation veteran notes, there is “a golden rule for false news: If one quarter of the content is true, that helps make the rest of it believable.”

MISINFO IS CREATED AND SPREAD FOR VARIOUS REASONS

Misinformation can be created and spread accidentally or purposefully. When purposeful, it can either be for auxiliary gains or for directly manipulating people via the infosphere. 5

One notable case of disinformation for financial gain is referenced in this evaluation of anti-vaxxer misinformation, noting “the canonical example… the 1998 publication by infamous former physician Andrew Wakefield purporting to show a link between autism and the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine.” Wakefield’s work on the autism-MMR link has been long discredited by the research community. Originally, one might think that he and his co-authors clunkily misinterpreted the information they had and reported their results without due diligence, but later findings report that Wakefield stood to profit significantly from fighting against the MMR vaccine. Still, the study’s damage was done: parents today continue to fear vaccinating their children, which allowed measles to reappear in the U.S..

Other disinformation can be created for political gain. Mid-2019, the New York Times reported on one of President Trump’s top media-creators, Patrick Mauldin, who created a quartet of look-alike political campaign sites for the top four Democratic candidates for the 2020 presidential race. Each website portrayed the candidates as racists, hypocrites, or ruthless, and labelled themselves as “a political parody built and paid for ‘BY AN American citizen FOR American citizens,’ and not the work of any campaign or political action committee.” These sites successfully deceived many citizens into believing they were the original campaign sites, distorting their opinions on the candidates. When asked for his motivations, Mr. Mauldin said he was “only trying to deliver hard truths. ‘I mean, [Democrats] could [see their candidates for who they were] themselves… But they’re not. That’s the problem.’”

Disinformation can also be carried out for ideological purposes. One educational and timely example of this can be found in the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA)’s tactics to sow polarization in the United States. The official report by the then-Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III of the U.S. Department of Justice goes into specific details on how the Russian strategy has played out since 2014 in order to “further a broader Kremlin objective: sowing discord in the U.S. by inflaming passions on a range of divisive issues… by weaving together fake accounts, pages, and communities to push politicized content and videos, and to mobilize real Americans to sign online petitions and join rallies and protests.” The effects of these initiatives can be seen by the numbers: on Facebook alone, there were “more than 11.4 million American users exposed to [Russian-sponsored] advertisements; 470 IRA-created Facebook pages; 80,000 pieces of organic content created by those pages; and [e]xposure of organic content to more than 126 million Americans.” Politico predicts that the 2020 U.S. presidential elections will see similar disinformation campaigns from within America.

MISINFO SPREADS VIA MANUFACTURED SOCIAL MEDIA ACCOUNTS

Disinformation is most easily amplified via fake social media accounts. These come in two forms:

- Bot accounts, which are made to share links, or other blog posts. 6

- Human-managed fake social media accounts, often organized into troll farms. 7

A few big roles that fake accounts play in disinfo campaigns online are:

Twitter has found accounts from countries all over the world pushing state agendas over the last three years, including Iran, Bangladesh, Venezuela, Catalonia, China, Saudi Arabia, Ecuador, the United Arab Emirates, and Spain. The Myanmar military spread anti-Rohingya messages on Facebook, using “its rich history of psychological warfare that it developed during the decades when Myanmar was controlled by a military junta… to discredit radio broadcasts from the BBC and Voice of America.” 10

Some methods used by disinfo campaigns, which are similar to those used by trolls online, are:

-

Ruining the opposing side’s reputation and community by purposefully pretending to be an extremist on that side. 11

-

Wasting opponents’ time or trying to ruin their image “by pretending to ask sincere questions, but… feigning ignorance and repeating ‘polite’ follow ups until someone gets fed up [in order to] cast their opponents as attacking them and being unreasonable”, commonly known as sealioning. 12

Disinformation serves to introduce mayhem and erode trust in communications, media, and society. As such, it is a particularly dangerous weapon against democracies.

AI + TECH’S POTENTIAL ROLE IN MISINFO

Readers may have noted that most of the techniques mentioned in HOW IT WORKS require significant human management and involvement. Thus, despite plenty of fear and noise blurring the dialogue, it’s important to remember that the technologies used in creating and spreading misinfo should not be as much a focus as the people and organizations using them.

Still, there’s no denying that AI & tech have enabled these behaviors on an unprecedented scale. In hopes of demystifying the technologies present in creating and spreading misinfo, we present a survey of technologies that are, or can be, used for misinfo.

TECH + AI WORSENING DISINFO CAMPAIGNS

For this section, we’ve broken our technologies into those which have already been used for disinformation and those which could feasibly be exploited in upcoming years.

NOW

In practice, most disinformation campaigns use groups of people to write and share biased and false content to manipulate public opinion. Oxford researchers found that 87% of countries use fake human accounts, 80% of countries use bot accounts (“highly automated accounts designed to mimic human behaviour online”) and 11% use cyborg accounts (“which blend automation with human curation”) to spread disinformation.

There’s still a lot of human interference in generating misinfo. 13 However, it is already possible for exploiters to use AI to generate misinformative content; there are informational step-by-step articles that break down how to create your own AI-populated troll farms and make deepfake videos. A polical campaign in India has used deepfakes to make campaign videos in languages the candidate does not speak. While the deepfake was produced under the direction of the political candidate, it is easy to see how this might be exploited by malicious parties. The resources and knowledge necessary for small scale campaigning is easy to obtain, and a great number of disinfo campaigns could not have occurred without bot farms or AI-generated content.

Targeting individuals

People used deepfakes to make fake sex videos of Rana Ayyub, a journalist in India who covers sensitive topics such as human rights violations, to ruin her reputation, distract her from her work, and spur the local community to harass her. 14

Targeting communities

Twitter has found accounts linked to governments and their campaigns, such as China’s tweets pushing back against the Hong Kong protests. By using their supporters and offering enticing wages, governments can gather large groups who are willing to write misleading articles, posts, and comments online under various pseudonyms. Other than supporting their own group’s ideals, bot farms also aim to irritate opponents to negatively affect the opponents’ reputations online.

Many groups use bot farms to generate hate against one another, like when these Turkish accounts popularized the hashtag #BabyKillerPKK to mobilize people against the Kurdish people. 15

Media Platforms

Bot farms have also been used to sow discord around anti-misinfo efforts, such as the information panel that YouTube introduced in late 2018 to combat misinformation around conspiracy-theory hot topics. Most of the users in this thread discussing how to remove the info panel are low-effort bot accounts; if you click the usernames and look at their activity histories, you find that most use generated usernames a la “User <number here>” or “<name><number>”, or that they have only been used once or twice to respond to this thread.

FUTURE

There are many potential technologies that could be used for misinfo/disinfo in the future: deepfake apps, article generators, and so on. Most sophisticated tech is usually not worth the intellectual investment for bad actors, but it doesn’t hurt to know what to look out for. We’ll go into what those are and how they work below.

Deepfakes

FakeApp.org appears to have been the primary source for personal deepfake generation, but currently it seems to be down (albeit possible to find with targeted searches). Now, it seems that people recommend DeepFaceLab for making deepfakes; there are tutorials for using both on YouTube. These and similar technologies are the most accessible for non-academics, since they require the least amount of tuning and technological savvy. Most advanced technologies require a significant amount of domain knowledge and resources to set up and train properly, which creates a steep wall for entry.

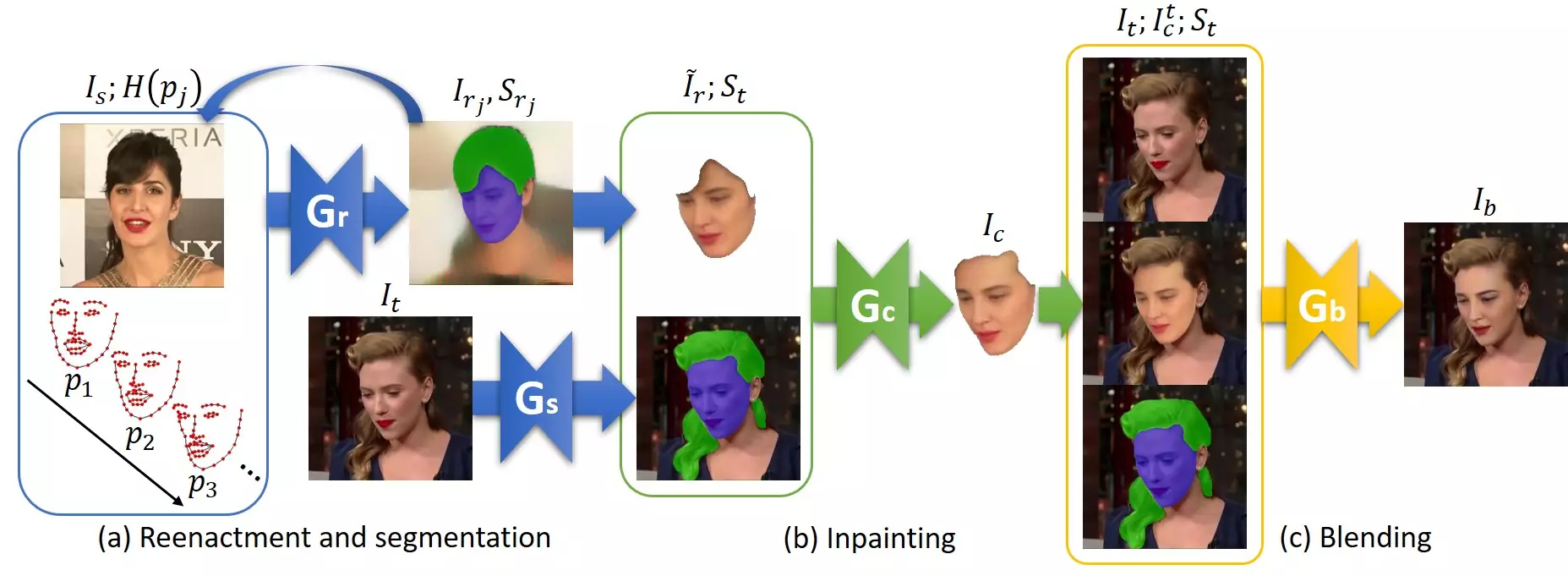

However, this barrier of entry is being lowered by the day. Off-the-shelf tools enabled a tech journalist to create his own deepfake video in two weeks with about $500. Dating apps are looking to use AI-generated faces to make their user base appear more diverse. Facebook recently announced how they shut down a disinformation campaign network of over “610 Facebook accounts, 89 Facebook Pages, 156 Groups and 72 Instagram accounts” that used AI-generated faces as profile pictures. The Face Swapping GAN (FSGAN) creates deepfakes without extensive training on the particular faces/actions the user wants to blend. Technology is making it easier for deep-fakers to create better results.

Text generation

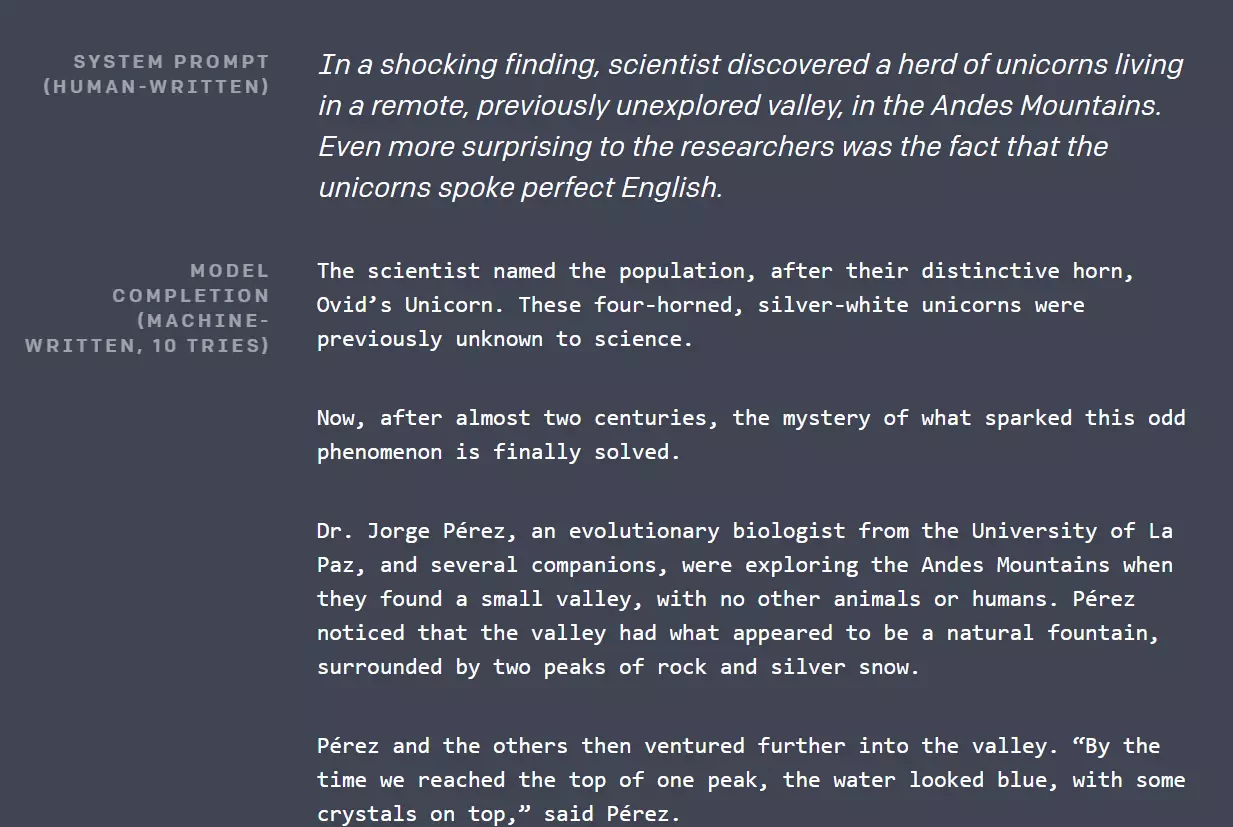

In the academic sphere, OpenAI’s language model GPT-2 was said to have potential misuses such as being used to “Generate misleading news articles”, “Impersonate others online”, and “Automate the production of abusive or faked content to post on social media.” After a period of releasing successively more advanced versions of GPT-2, OpenAI recently released the most advanced version which you can demo online here, and reported that they’ve “seen no strong evidence of misuse so far.”

Another cutting-edge model for generating misinfo is GROVER, which, given any headline, can generate a full article. In testing, “humans find these generations to be more trustworthy than human-written disinformation.” Thankfully, content-generation technologies are far from perfect. Most reviews of GPT-2 generated text say it doesn’t hold up well to critical inspection.

One of WIRED’s AI & tech policy staff writers, Gregory Barber, rightly points our attention to the fact that most generated fakes are still relatively easy to identify. Still, Barber reminds us experts like law professor Robert Chesney say that “political disruption doesn’t require cutting-edge technology: it can result from lower-quality stuff, intended to sow discord, but not necessarily to fool.” Since many people just read headlines and skim the rest of the article, GPT-2’s level of sophistication is sufficient for general-purpose deception. If readers don’t consume content critically — which they often don’t — imperfectly generated content could still easily influence their minds on important issues. 16

That said, though fancy new technologies and AI may seem foreboding, they don’t really bring anything new to the table other than allowing scammers and bad actors to streamline their processes and reach a wider audience — and even then, said scammers rarely use them.

TECH + AI WORSENING THE EFFECTS OF UNINTENTIONAL MISINFORMATION

Bad actors simply don’t need to invest in sophisticated technologies to deceive their intended audience. All they need to do is take advantage of everyday technologies. For this section, we look only at previously or currently available tech and AI.

Social media optimizations

Algorithms such as multi-arm bandits and various machine learning models play a key role in optimizing user engagement and keeping us returning to social media and scrolling mindlessly. The biggest social media platforms are all the products of companies, whose survival depends on ad-generated revenue.17

Often times, the recommended content are either mindlessly entertaining or highly polarizing which elicits strong reactions, which can be easily created by bad actors. Both types of content can lower people’s vigilance and allow them to fall prey to misinformation.

Active exploitations of seemingly neutral technologies

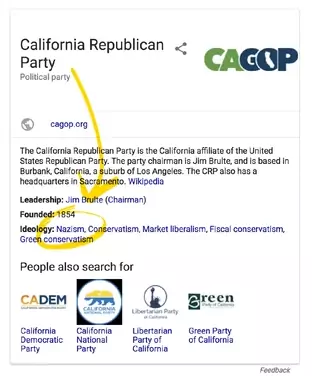

Google’s search engine is widely viewed as neutral, but even their services have been exploited to spread disinformation. Google has contextual knowledge panels, which serve as “a collection of definitive-seeming information… that appears when you Google someone or something famous,” which appear next to their query results. While these knowledge panels are monitored, they are populated automatically from partner sites, which bad actors can exploit to amplify false information.

Another way to take advantage of Google search is through search engine optimization (SEO), or the “process of maximizing the number of visitors to a particular website by ensuring that the site appears high on the list of results returned by a search engine.” This is done by many companies for marketing purposes, but it has become a co-opted troll tactic. One such example of troll SEO is when thousands of Reddit users upvoted a picture of President Trump which was captioned with the word “idiot” until Google’s query results for “idiot” returned his image first. Another major vulnerability to ill-intentioned SEO is the data void, which consists of “search engine queries that turn up little to no results” which can be easily taken over and populated primarily “by manipulators eager to expose people to problematic content.”

Old news-consumption methods in a new world

Social media usage is increasing around the world, and many communities new to the infosphere do not have the digital literacy infrastructure or social norms in place to prevent them from believing much of what they see online. BBC’s 2018 study on the spread of misinformation in India, Kenya, and Nigeria found that participants:

made little attempt to query the original source of fake news messages, looking instead to alternative signs that the information was reliable. These included the number of comments on a Facebook post, the kinds of images on the posts, or the sender, with people assuming WhatsApp messages from family and friends could be trusted and sent on without checking.”

Technology has been a great equalizer in terms of lowering the barrier to entry for people to easily create and spread information, but that has also shifted the information landscape in ways that consumers haven’t adjusted to.

MITIGATING THE EFFECTS OF MISINFO

Thankfully, organizations of all types and sizes are aware of and working to counter misinfo’s effects. This is an active area of research, but we’ll provide a sweeping survey of these efforts — including non-technological initiatives. Many of the cited organizations provide their own pros and cons for their efforts, or those discussions can be easily found online, so we won’t go into them here.

COMPANIES

The creators of some of the biggest technologies which have amplified misinfo online, such as Facebook (which also owns WhatsApp), Twitter, and Google (which also owns YouTube), are taking various steps to combat “coordinated inauthentic behavior” on their platforms. 18

Preemptively identifying and informing users of problematic content

Existing fact-check and content-moderation pipelines such as those used at Facebook rely primarily on human workers, but companies are expanding automated fact-checking and content moderation using machine learning models. Tattle is a startup that connects WhatsApp users to special fact-checking channels, in which ML can “automatically categorize those tips and distribute relevant fact checks.” Facebook has made efforts to use ML to moderate content in various ways, such as by flagging videos that contain violent, mayhem-inducing content. Google introduced information panels mid-2018 on YouTube videos covering “a small number of well-established historical and scientific topics that have often been subject to misinformation,” automatically linking to sources that strive to give users further context on those videos.

Combating false amplification of ideas on their platforms

One thing social media companies can do to combat misinfo is removing harmful and misleading content from their platforms, although this rightfully raises questions on whether big tech companies should be regulating online speech. Twitter banned all political and other advertisements from state-controlled media, and it recently committed to labeling deepfakes and any other “deliberately misleading manipulated media likely to cause harm.” By contrast, Facebook has not removed false political advertising from the website, although it has been taking down misinfo posts regarding the coronavirus outbreak.

Ongoing works in industry aim to identify misinfo both from the content itself and from the activities of the content authors. Leading cyber-security firm FireEye trained a GPT-2 model to detect Russian IRA-style texts by first training a generative model on IRA propaganda, then training a separate detection model to detect both generated and original IRA text. Mid-2017, Facebook reported its work to “recognize inauthentic accounts” engaged in false amplification by looking at “patterns of activity” instead of the content that they share–which is related to networks research that has been done in media studies for years. Taking a similar approach, Twitter acquired the machine-learning startup Fabula AI mid-2019 to strengthen its efforts in detecting network manipulation.

Funding news initiatives and shaping the news ecosystem

Mid-2017, Facebook co-funded the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism’s News Integrity Initiative, which is working with universities and journalism centers to create “a global consortium focused on helping people make informed judgments about the news they read and share online.” 19 Google started the Google News Initiative in 2018, which aims “to help journalism thrive in the digital age” (primarily by building on the news ecosystem and creating fact-checking tools), as well as co-started the non-profit First Draft, which “supports journalists, academics and technologists working to address challenges relating to trust and truth in the digital age.” In late 2019, Twitter collaborated with Adobe and the New York Times to start the Content Authenticity Initiative, to “provide proper content attribution for creators and publishers” and “provide consumers with an attribution trail to give them greater confidence about the authenticity of the content they’re consuming.”

To aid deepfake detection research, Google released a large dataset of videos altered by deepfake technology and their unaltered counterparts. The Partnership on AI, an organization with members including Amazon, Facebook, and Microsoft, also hosts a Deepfake Detection Challenge.

As organizations on the front lines of technologies that are used for misinformation, companies often have the greatest knowledge of patterns of misinformative behavior and the best datasets for training.

ACADEMIA

Academics from all disciplines are studying misinformation online. 20 Their works helps us understand the scope of the problem.

Identifying generated content

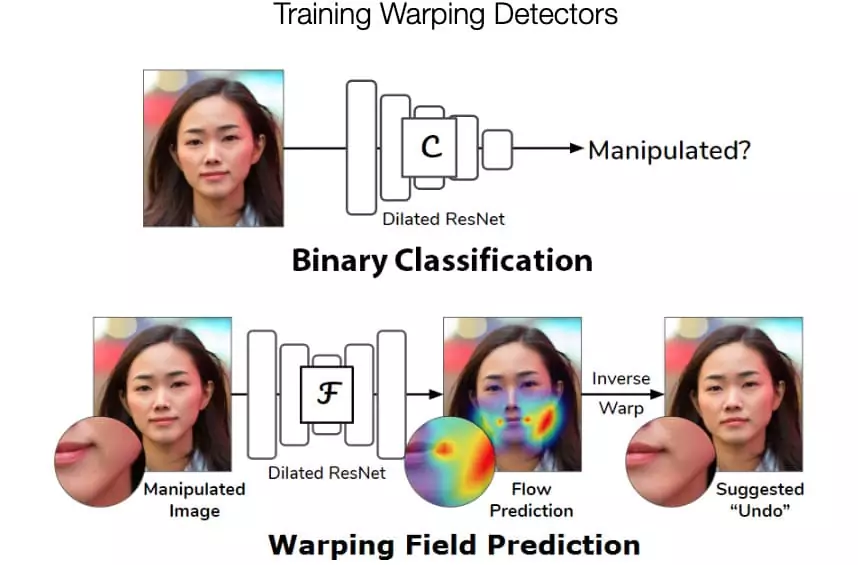

The researchers behind both GROVER and GPT-2 (the text-generation models we mentioned before) have trained models to detect texts generated by their technologies. GROVER’s detection model reports a 92% accuracy on detecting generated texts as non-human, and GPT-2’s detection model reports 95%. 21 Researchers from Adobe and UC Berkeley trained an AI model that can detect if an image has been warped by Photoshop. The Photoshop research also looks into how to “undo” warping and reconstruct original images. Google also released a similar tool to “spot fake and doctored images.” Some take a more crowd-sourced approach - Reality Defender takes in reports of suspected fake media from its users and labels suspicious online content with a browser plugin.

Automating fact-checking

Researchers at the University of Texas at Arlington released ClaimBuster, a real-time automated fact checking tool which detects assertions of facts from transcripts (for example, of presidential debates) and forwards statements that merit fact-checking to journalists. The website also has an “end-to-end fact-checking” tool that tries to match input statements to ones that have already been fact-checked, effectively allowing users to search its database. Students at UC Berkeley built SurfSafe, “a free browser extension… that detects fake or doctored photos” by checking them against a database of known manipulated images.

Embracing interdisciplinarity

Misinformation is an old, complex, and interdisciplinary problem, and technology is far from the only way to address this problem. To foster collaboration among researchers across different fields, several misinformation conferences have been organized, such as MisinfoCon (MIT), the Information Ethics Roundtable focusing on “Scientific Misinformation in the Digital Age” (Northeastern University), and the International Research Conference focusing on “Fake News, Social Media Manipulation and Misinformation” (various universities around the world) – just to name a few. 22

Interdisciplinary researchers approach misinformation in markedly different and thereby valuable ways. For example, danah boyd (founder of Data and Society), Claire Wardle (co-founder of First Draft), and David G. Rand (associate professor of Management Science and Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT Sloan) focus on situations such as how YouTube’s algorithms lead to hyper-radicalization, how BBC decides whether to trust a new plethora of first-hand information, or “user-generated content”, and how social networks constrain the free flow of information, refining the problem’s scope in the process.

NEWS OUTLETS

News outlets that care about news integrity remain potential grounding forces in the information ecosystem. Some notable examples of the counter-misinfo efforts I’ve seen are provided below.

Giving users context

Context is important for any news story, but the chronological context of a headline is often lost when it is shared through social media as users (unintentionally) and publishers (intentionally) recycle outdated articles. The trouble with this practice is two-fold: sensational old news often become fake news as newer information debunk old claims, and sharing the same story over and over again gives the impression that the event it describes happens more often than it does.

To combat this issue, publishers like The Guardian have begun drawing attention to their article’s ages with small but notable design changes:

They also add the year of publication when the article is posted on social media:

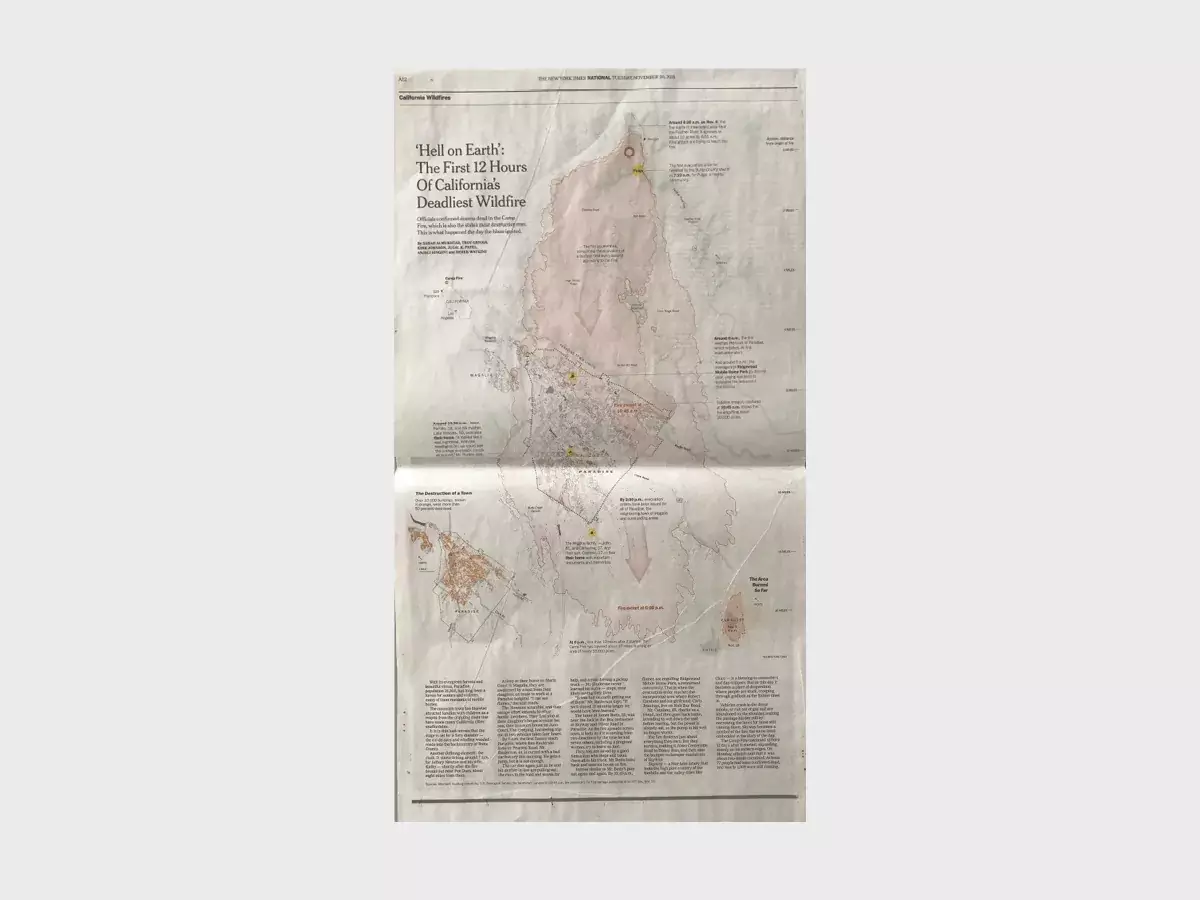

Communicating complex ideas effectively

The New York Times has been particularly innovative in developing new ways to easily and accurately communicate ideas to their users via remarkable data visualizations (these have consistently won Malofiej Awards, known as the Pulitzers for infographics). Their data editor Amanda Cox is well-known for adding to the Times’ communication ability, as they prioritize bringing to light more information “in ambitious enterprise stories, investigations as well as everyday news stories — that would be hidden but for creative investigation of data.”

COMMUNITY

As companies, academia, and news outlets mitigate the spread of misinformation from a top-down perspective, communities work from the bottom up. The number of fact-checking organizations around the world continues to grow, and there are many ongoing initiatives to teach digital literacy specifically in the context of determining misinformation. One such initiative is the News Literacy Project, a national educational nonprofit founded by a Pulitzer prize-winning reporter. The project offers “nonpartisan, independent programs that teach students how to know what to trust in the digital age”.

Beside grassroots organizations, governments around the world have begun taken legislative action against misinformation, although such efforts bring up very important arguments about free speech and censorship.

The Online News Association compiled a large list of open initiatives in 2017, which can be found here. It includes collaborations and coalitions working on fact checking and verification, guides on how to handle content online, initiatives and studies on restoring trust, and related events and funding opportunities. 23 Addressing misinfo is a matter of not only hitting the problem head on, but also creating an ecosystem in which high-quality information are shared, and people are diligently doing so.

CONCLUSION

Modern information warfare is a sophisticated problem, and AI only makes up one part of the phenomenon. It’s important to think of “technology as an amplifier of human intention.” Technology itself won’t be nefarious unless the users or designers had those intentions in the first place. As such, mitigating misinformation is a highly interdisciplinary task and requires fearless, creative thinking.

So what can we do? Brookings summarizes it well:

- Governments should promote news literacy and strong professional journalism in their societies.

- The news industry must provide high-quality journalism in order to build public trust and correct fake news and disinformation without legitimizing them.

- Technology companies should invest in tools that identify fake news, reduce financial incentives for those who profit from disinformation, and improve online accountability.

- Educational institutions should make informing people about news literacy a high priority.

- Finally, individuals should follow a diversity of news sources, and be skeptical of what they read and watch. 24

There is a future for trustworthy and healthy information, but much work needs to be done.

DEEPER DIVES

While I’ve done my best to provide an introductory look into the state of disinformation with this article, there are natural limitations to the information I can offer, and I hope readers are patient with the gaps in my knowledge. I’d like to encourage interested readers to go forth, knowing how muddled the field can be, and look up more information yourself with sufficient skepticism and humility.

Here are some papers/topics/resources that I recommend, many of which were referenced in this article:

- Oxford University’s report: The Global Disinformation Order: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation

- Michael Golebiewski and Danah Boyd’s concept of Data Voids: Where Missing Data Can Easily Be Exploited

- Harvard’s case study on How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Distraction, not Engaged Argument, which provides a fascinating look at one way that disinformation can be used

- BBC’s research on differing worldwide responses to, and contexts for, misinformation in India, Kenya, Nigeria

- The book Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming

- Christoph Koettl’s Citizen Media Research and Verification: An Analytical Framework for Human Rights Practitioners, which brings up interesting case studies for the importance of verifying “citizen media” as well as strategies for doing so.

Citation

For attribution in academic contexts or books, please cite this work as

Janny Zhang, “Bots, Lies, and DeepFakes — Online Misinformation and AI’s Role in it”, Skynet Today, 2020.

BibTeX citation:

@article{zhang2020onlinemisinfo,

author = {Zhang, Janny},

title = {Bots, Lies, and DeepFakes — Online Misinformation and AI's Role in it},

journal = {Skynet Today},

year = {2020},

howpublished = {\url{https://www.skynettoday.com/overviews/misinfo } },

}

-

Their digital literacy, or the “ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information,” is often underdeveloped, which makes them easier targets of disinfo campaigns and 7x more likely to share misinfo than younger folks. ↩

-

Even if younger Americans are usually better at telling opinion from fact than the elderly, repeated exposure to misleading headlines can semi-permanently affect their first impressions of various topics during a crucial age for developing opinions. ↩

-

Furthermore in India, people often forego fact-checking in favor of promoting content that support nationalist attitudes. ↩

-

When the Chinese deep fake app ZAO attracted the attention of the Western world, Westerners proceeded to panic over the implications of the technology and whether or not ZAO was a front for the Chinese government to gather more data about users, though the truth is that China has already rolled out significantly more invasive forms of surveillance (which varies by region). Russia was found to spread anti-GMO disinformation, possibly to drive more buyers towards its own “ecologically safe” agricultural products. ↩

-

Confirming the purpose behind disinformation can be very difficult (especially since perpetrators rarely confess their motivations) and remains an open-ended task today. ↩

-

In 2018, Pew Internet researchers found that 66% of tweeted links are shared by bot-like accounts. ↩

-

In 2015, the New York Times reported on the Russian IRA’s method of paying people to work disinfo content creation jobs, which required “two 12-hour days in a row, followed by two days off. Over those two shifts [workers] had to meet a quota of five political posts, 10 nonpolitical posts and 150 to 200 comments on other workers’ posts” for “41,000 rubles a month ($777).” ↩

-

Twitter has released huge datasets of state-backed throw-away Twitter accounts which have helped share bits of information, which distorts users’ impressions of how popular those ideas are. ↩

-

Paid state actors from China coordinated to exploit in-platform reporting mechanisms to take down opposing views on Instagram. ↩

-

As mentioned earlier, Oxford has a more detailed report on the tactics that countries around the world have been using for computational warfare. ↩

-

In 2017, a number of white supremacists created fake accounts pretending to be African Americans to take “revenge on Twitter” for banning some white supremacist and anti-Semitic ads, as well as to “[cause] blacks to panic.” ↩

-

Amy Johnson, a researcher at the Berkman-Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University, goes into the long-lasting effects of sealioning in an essay in Perspectives of Harmful Speech Online. ↩

-

For reference, read more about Russia’s disinformation strategies which have spanned decades in their planning and execution, detailed more formally here and analyzed here by political scientist Stefan Meister. ↩

-

Similarly, this tactic has similarly been used on various celebrities, mostly female, to create pornographic content for “consumer enjoyment,” which can affect these celebrities’ reputations or wellbeing as well. Notable celebrities whose likenesses have been exploited towards this end are Gal Gadot, Emma Watson, Seolhyun, and Natalie Portman. ↩

-

Their primary tactic was to group the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), which is not a terrorist group, with the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), which is publicly acknowledged by many countries as such. ↩

-

For example, a researcher trained a GPT-2 model to generate fake comments which were submitted to a federal public comments website, and human readers were incapable of telling if a comment is genuine or fake better than random chance (you can try looking at these comments yourself here). ↩

-

- Facebook + Instagram’s Form 10-K, 2018: “The loss of marketers, or reduction in spending by marketers, could seriously harm our business. Substantially all of our revenue is currently generated from third parties advertising on Facebook and Instagram.”

- Twitter’s Form 10-K, 2018: “The substantial majority of our revenue is currently generated from third parties advertising on Twitter. We generated approximately 86% of our revenue from advertising in each of the years ended December 31, 2017 and 2018.”

- Google’s Form 10-K, 2018: “We generated over 85% of total revenues from advertising in 2018.”

-

Here are a number of articles and YouTube videos going into some of the things each specific platform does to combat misinfo: Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, Google, and YouTube. ↩

-

though the initiative has since refocused on “improving diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) practices in the news business” ↩

-

We’ve already cited many universities researching the state of misinformation, such as Oxford (2019 Global Misinformation Order), University of Cambridge (Citizen Media Research and Verification), and Stanford (Evaluating Information). ↩

-

Of course, both groups are wary of relying on those detection models to determine generated content from other models. ↩

-

One such conference, and some of its attendees: in 2017, Harvard and Northeastern University came together to host a conference on “Combating Fake News,” where they decided on “An Agenda for Research and Action,” publishing its takeaways. This was sponsored by Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy and their Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation; Northeastern University’s NULab for Texts, Maps, and Networks and their Network Science Institute; featuring presentations from folks at institutions and companies such as MIT, BBC, the Council on Foreign Relations, UpWorthy, FactCheck.org, Microsoft Research, and Twitter — truly a mix of academia, industry, technology, policy, information science, and other fields. ↩

-

Some of these initiatives are mentioned in this article already. ↩

-

One way of starting to do so is looking into the News Literacy Project, which has many tips about common fallacies in news such as “This apple is not an orange! And other false equivalences”. I’d personally add that once individuals have educated themselves about the state of misinformation, they should share that knowledge with their own communities. Also, those particularly interested in mitigating misinformation should join or support the above groups. ↩