So-So Artificial Intelligence

Could mediocre AI threaten labor more than brilliant AI, under the right conditions?

A lot of the conversation about the future of AI and automation focuses on the AGI endgame (“will humans still work when artificial general intelligence can do everything?”). But there are more interesting, tractable, and concrete questions to answer about the effects of “narrow,” task-specific AI that looks more or less like what we have today. In the near future, we can expect more advanced robotics, autonomous cars, customer service chatbots, and other applications powered by such narrow AI to take over certain tasks from humans. Should we be optimistic about labor in the next 10-50 years, when parts of industries will be automated by narrow AI? What early signs of those trends should we be concerned about now?

There’s little controversy that AI adoption will cause short-term job losses – as has been the case with past industrial revolutions that ultimately left most better off. The question is whether AI-enabled automation will bring about lasting unemployment – is this time going to be different? The commonly held view is no: as we reap the benefits of tech-enabled productivity gains, as with past technological advances new sectors and jobs will recoup the losses. Just imagine a more efficient future of autonomous vehicles, with new jobs around redesigning cities / infrastructure and more time for otherwise frustrated commuters to work and play. In Mary Meeker’s “2018 Internet Trends Report,” (a staple of the startup media diet), she echoes this thought:

“Will technology impact jobs differently this time? Perhaps … but it would be inconsistent with history as … new jobs/services + efficiencies + growth typically created around new technologies.”

As we’ll see, automation might not inherently work this way. The way we deploy AI-driven technology in the near term may change whether we see lasting negative effects on jobs.

“So-so” automation

First, let’s dig into whether the technological and economic drivers of our current situation do indeed match historical precedents. “Automation and New Tasks” (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019) clarifies some of these dynamics. In particular, they highlight some interesting and critical nuances that often seem to be glossed over:

1) It’s important to distinguish between the effects of automation and the effects of new (work) tasks.

New industries have historically followed new technology and automation, often as a direct consequence. The mechanization of agriculture in the 20th century automated agricultural jobs but replaced them with manufacturing ones. The invention of the aircraft drove unemployment in the railroad industry but recouped those jobs with the creation of the aviation industry.

Still, it’s wrong to assume that automation necessitates the creation of new roles for humans. More specifically, if we account for the fact that automation can change job descriptions (e.g. a factory worker’s job might change from creating a part to overseeing a robot that creates the part) and analyze individual tasks, we see that automation might not always create new tasks for humans.

In many past cases, additional organizational and technological innovation were necessary for new industries to flourish and counterbalance job loss from automation. The airplane itself did not create new jobs; it was the new organizational processes around air traffic control, tarmac support services, safety inspection, and more that made space for thousands of people to have a role in the industry. In the case of aviation, these new roles might be unavoidably coupled with the core invention of the aircraft, but the critical point is realizing that this might not be the case for all new technologies.

The analysis in the paper separates the effect of automation from the effect of new tasks on labor demand, making it explicit that automation itself doesn’t necessarily signal the creation of new sectors and tasks.

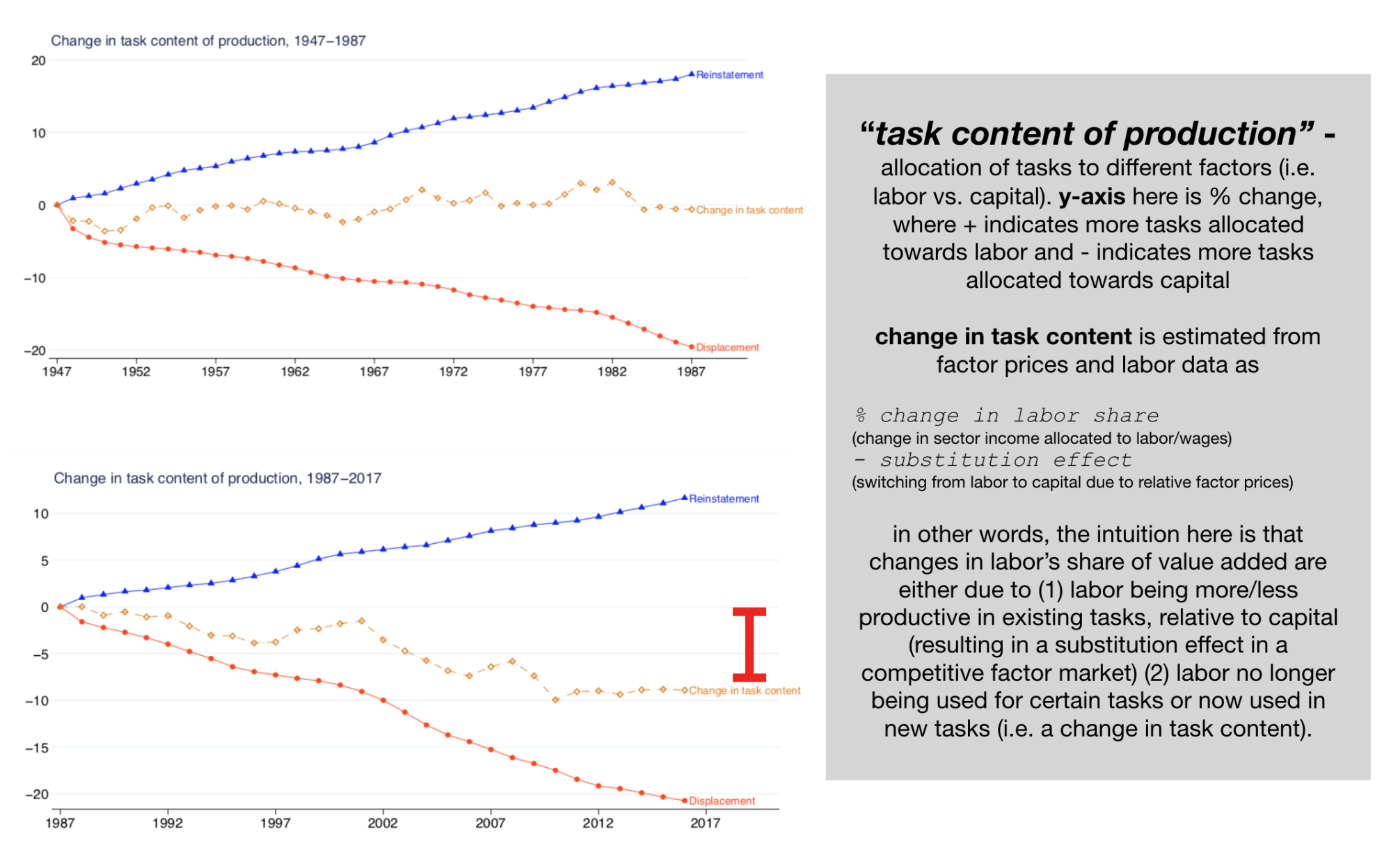

In practice, can we actually separate automation and new tasks? Recent labor data (see graph below) shows that automation and productivity are increasing, but new tasks aren’t being created at nearly the same rate. It’s unclear if this is simply because we’re still in the early phases of the tech adoption cycle (not enough time for new infrastructure and industries to leverage new tech), but it’s still a deviation from historical trends, which suggests we might be on a different path.

2) Automation increases productivity, but not always by enough to increase labor demand.

Automation itself replaces humans with capital (machines), what Acemoglu and Restrepo call the displacement effect of automation. This force towards decreased labor demand is offset by the fact that efficient tech-enabled firms can produce more, and scaling up production results in the productivity effect, which is the increase in demand for both automated and non-automated tasks.

The ultimate effect of automation itself (ignoring longer-term changes requiring the establishment of whole new industries, as described before) is a balancing act between these two forces. The problem is that automation does not necessarily increase productivity by enough to offset the displacement effect. If automation is only slightly better than humans, and not that much cheaper, labor demand will decline.

These two points combined means that we should be especially concerned about the future of labor if new tasks aren’t being created at a rate that offsets the tasks that are being displaced, and new automation is not that much more productive. These two dynamics result in a particularly strong shift against labor – that is, there being fewer jobs and people suffering because of it.

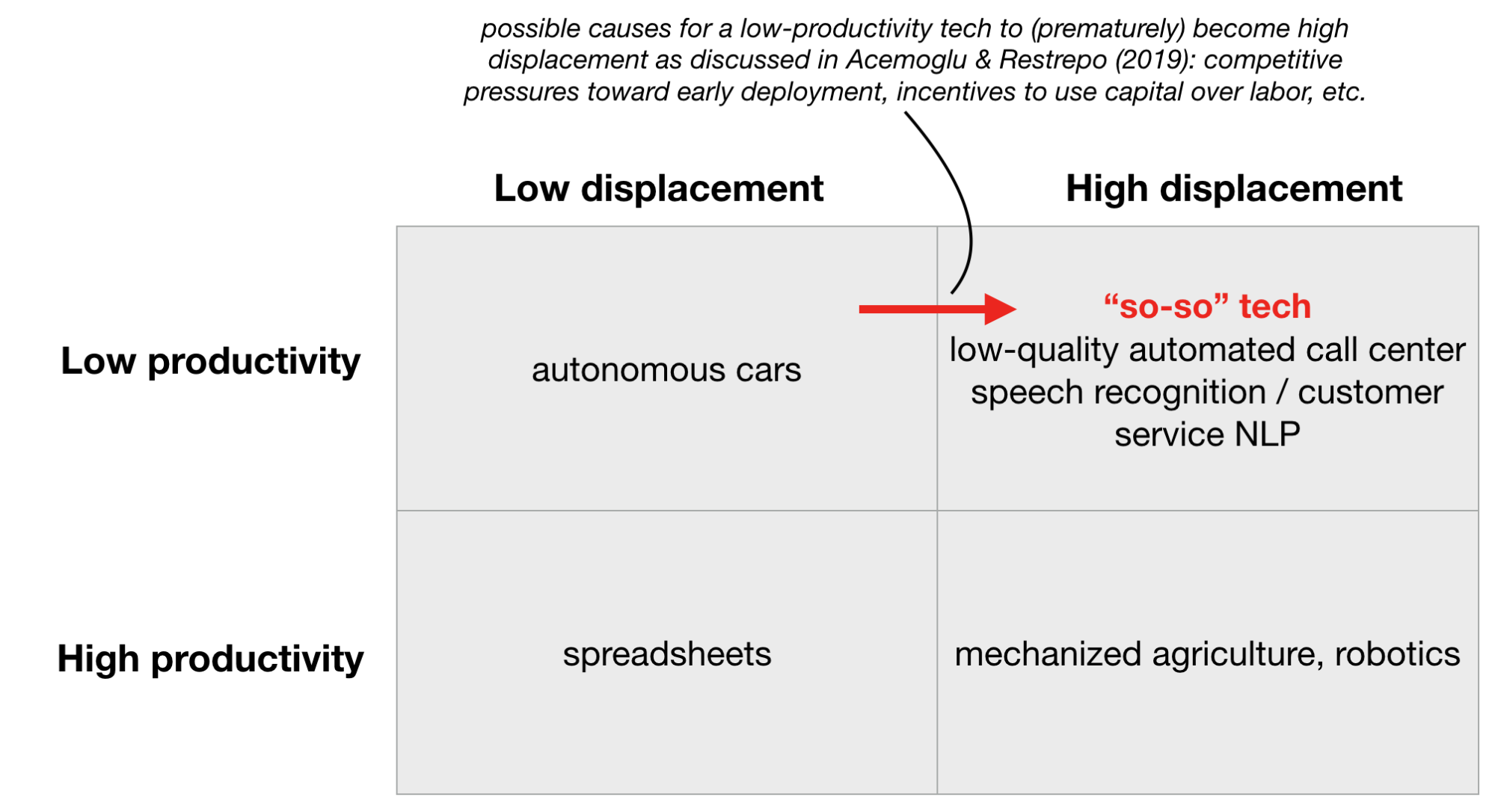

It’s an un-intuitive but important point: we should be more concerned that mediocre technology will depress labor than brilliant technology that is significantly better than humans, because the former may not lead to sufficient counterbalances to job displacement.

Avoiding “So-So” AI automation

Automation in certain industries has been highly productive. Still, many hot applications like facial recognition and customer service chatbots are known to be merely “so-so” — they can potentially displace a lot of workers without significantly improving productivity. The paper posits several reasons for why we’re seeing these trends recently, but the one I find particularly important is the culture around AI in industry and academia.

Research designs for humans out of the loop.

Research methodology tends to abstract human factors out of the problem for the sake of solving a well-defined task. Success is benchmarked by solving tasks like recognizing images or answering questions end-to-end. It is rare to see systems that are designed so that humans and machines are solving tasks jointly, or where the machine is envisioned and evaluated as a tool in a larger process. Although the AI community is starting to interact with more human-focused fields like human-computer interaction, this kind of thinking is still not mainstream.

Hype about AI drives premature deployment and end-to-end automation.

Many AI startups today compete to be the first to market with new research. It might be easy to build an 80% working MVP, but the last 20% — edge cases of the real world — is many times harder. While autonomous driving has been good enough to take cars out for a test drive on real roads, they are still unreliable difficult conditions like a dark road or a winter storm. Companies bet that collecting more data will be a panacea for poor performance, but it looks like many of them end up as pseudo-AIs that are indefinitely human-powered behind the scenes. Where humans used to play a central role, they instead label data to improve mediocre automated systems.

The mistake might be underestimating the long tail of such edge cases we need to address before machines even approach human-level performance in tasks such as translation or driving. This is even without considering potential safety failures or performance in adversarial or biased conditions!

For example, many companies are working towards replacing parts of the customer service process with chatbots. Unfortunately, despite recent advancements in natural language processing, the state of language understanding falls far short of the ability of any human. Substituting human workers for automated solutions would be replacing highly effective, reliable, and cheap labor with so-so technology. I don’t know many people who haven’t been frustrated with an automated customer service line or chatbot at some point, trying to guess at the easiest path to speaking to a human. These are the kinds of cases where the net productivity effect is most likely to be too small to spur the creation of new tasks.

Although companies have not quite reached the point of displacing workers entirely, there are strong competitive pressures to do so as soon as possible. As the co-founder of human-in-the-loop scheduling company shared,

the most common question investors asked us while developing a worker-in-the-loop scheduling service (Clara Labs) was “how long until the humans are gone?” Look no further than the speculations as to when (not if) Uber and Lyft will replace all of their drivers with self-driving systems. Investors are seeking scalable, high gross-margin businesses; large human workforces don’t obviously fit the mold.

In addition to economic pressures, the mystique and cultural baggage of AI emphasizes fully autonomous systems. This leads companies to pitch and demo flashy “fully intelligent” agents like Google Duplex, which (supposedly) demonstrated impressive human-like abilities:

Companies stretch their products to make them seem fully autonomous and race to achieve it, even when the technology isn’t quite there. The result might just be so-so automation.

Conclusion

These concerns might dissipate as so-so technologies improve, but they may potentially do so at a great, although preventable, socioeconomic cost. While technology has to be “so-so” before it becomes good, entrepreneurs and practitioners do have a choice in when to pull research results into industry. Ideally, the AI community might strive for stronger community norms around using AI in practice to offset competitive pressures; companies might think twice about using a subpar system in production if there were clear consequences on their public image. The community also needs to educate people outside of the technical community on the benefits and risks of deploying AI products in the real world, aligning technical people who understand the limitations of the technology with non-technical decision-makers (policymakers, company executives, consumers).

There’s been more of a push in the academic community towards human-centered AI (see Stanford’s HAI or Berkeley’s CHAI). So-so AI applications would be ideal candidates for hybrid human-AI work (and I hope in ways more substantial than humans labeling data for AI!). Innovations that make way for humans might drive the introduction of new tasks following automation (as Acemoglu & Restrepo explore in a companion paper, “The Wrong Kind of AI”). If researchers do indeed believe in “augmenting human capabilities,” they need to change their research agendas to do so, perhaps by:

-

Studying human-robot or human-computer interaction

-

Thinking about what humans are uniquely good at, and focusing efforts on tasks they’re bad at

-

Designing machine learning systems in the context of a larger loop to work with partial human work / inputs, or incorporate human feedback post-output

There’s definitely a lot more work on the economic effects of automation that I haven’t touched, but I left Acemoglu & Restrepo’s paper with an interesting explanation for the dynamics at play. Their story complements the popular discourse that simply assumes that the balance sheet always works in favor of new technology. The reality is, we can neither expect nor afford to rely on new jobs to materialize. Both academia and industry are actively trying to engineer fully automated systems over human-augmenting ones. If we are to do better, we need conscious design, reorganization, and further innovation in both technology and society.

This is an updated version of a post from Jessy Lin’s blog. Thanks to Sahaj, Max, and Nikhil for feedback!