Has AI surpassed humans at translation? Not even close!

Neural network translation systems still have many significant issues which make them far from superior to human translators

Media outlets have recently reported that AI-powered software can translate text as well as expert human translators. Provoking headlines include:

- The Verge - Google’s AI translation system is approaching human-level accuracy

- Quartz - AI-based translation to soon reach human levels

- ZDNet - Microsoft researchers match human levels in translating news from Chinese to English

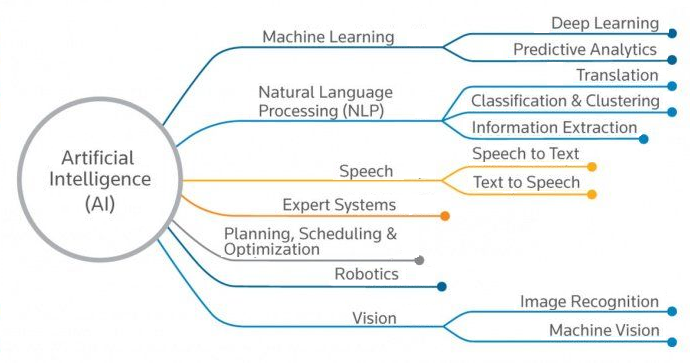

This apparent success is due to the advent of Neural Machine Translation (NMT), a method using neural networks to perform machine translation (we’ll define these terms in the next section). The technique works extremely well due to its ability to leverage very large amounts of translation data. Accordingly, major tech companies such as Google and Facebook have adopted NMT in the last few years, resulting in higher quality translations.

But are NMT systems comparable to human translators, like these headlines imply? Not even close. As we’ll see, present day NMT systems are not quite as good as they have been purported to be. They still fail at many essential aspects of translation, and are very far from superseding humans.

What’s Neural Machine Translation, in simpler terms?

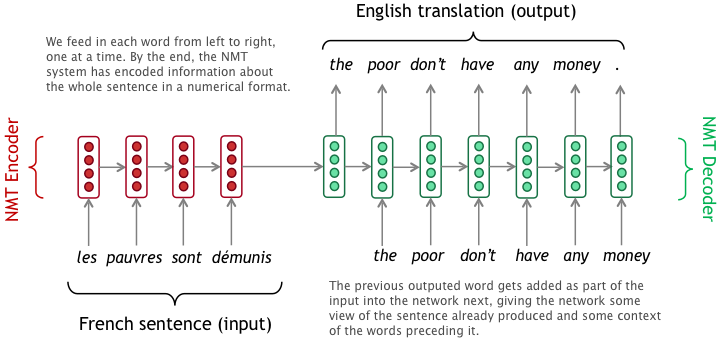

Machine Translation (MT) is a branch of AI concerning the use of software to translate text from one language to another. Neural Machine Translation (NMT) is a relatively new method that uses neural networks to perform machine translation. A neural network is a system that can be trained to recognize patterns in data, thereby transforming some input data (e.g. a French sentence) into a desired output (e.g. the input sentence translated to English). Let’s take a look at an example NMT system:

Consider translating a sentence from French to English. In this context, the general process for NMT is as follows: You feed the input French sentence into the network, where each word of the sentence is represented by vectors of numbers so that the network can process it. Then the network performs many mathematical transformations on those numbers, ultimately producing a sequence of new numbers that represent the English output sentence.

At least, that’s the main idea. In practice, there are several important steps:

- Before any translation can happen, the human engineers need to decide the architecture of the network, i.e. how many and what type of mathematical transformations the network should apply. This requires significant expertise, a lot of experimentation, and a fair amount of guesswork. Once the network architecture has been decided, we have an untrained neural network.

- The engineers then implement this network on computers with heavy processing power.

- The network is then trained: a program is run to input millions of French and English sentence pairs (i.e. translations of the same sentence) into the network. With each sentence pair, the network first sees the French sentence, guesses what the English translation should be, and then is told how accurate its guess is relative to the provided correct English translation. Over many iterations, this training process enables the network to find the best settings associated with the mathematical transformations, and thus produce good English translations.

- Finally, the engineers test their NMT system by having it translate sentences that weren’t used during training, to make sure it can generalize beyond the data it was tuned to work well on.

To make the above possible, we must also collect large amounts of training and test data. Fortunately, an enormous quantity of French to English text can be found on the web: there are news articles, TED talks, Wikipedia pages, and EU proceedings that have translations into both languages. Together, these datasets give us a diversity of vocabulary and style, since they come from various contexts. The more translation examples we can get, the better our network can learn to translate unfamiliar phrases, using patterns it has previously seen during training.

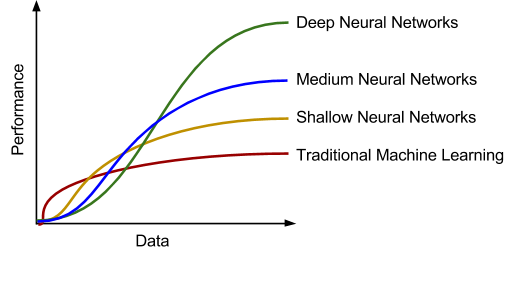

With great data come great neural networks

Neural networks have recently met success because of the rise and availability of large amounts of data. In particular, deep neural networks (that is, neural networks with many layers of depth, which enable the network to compute more complex mathematical functions) see extraordinary gains in performance when enough data is provided. In fact, with enough data and a deep enough network, sentences translated by NMT systems are much more fluent than those by previous techniques. Here, “fluency” means that the output text sounds less clunky, and in the best cases could be mistaken as an actual person’s writing.

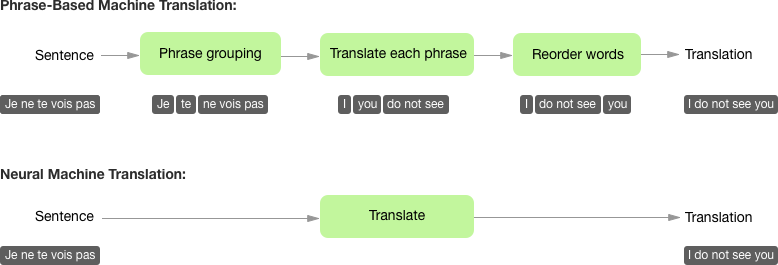

Neural networks also provide the advantage of end-to-end learning. This means that we don’t need to do a lot of work processing data between a French sentence and its English translation. By contrast, prior methods such as Phrase-Based Machine Translation rely on multiple intermediary steps to translate a single sentence. Systems like these are extremely complex, comprising of many separate sub-components that must be dealt with separately, requiring a lot of work from large teams of engineers. NMT systems are comparatively simple to build, requiring less work and less decision-making from human engineers.

What’s wrong with NMT?

Back to those headlines we started with – NMT sounds pretty extraordinary, but is it really comparable to human translation? Not at all. NMT is in fact still flawed in many ways that are distinctively _un_human.

These flaws can be broadly described by 3 categories: reliability, memory, and common sense.

- Reliability: Perhaps most worryingly, NMT translations can be unreliable, offensively wrong, or utterly unintelligible. NMT systems have no guarantees about accuracy and often miss negation, whole words, or entire phrases.

- Memory: NMT systems also have really acute short-term memory loss. Currently, we have built our systems aimed at translating one sentence at a time. As a result, they forget information gained from prior sentences. This is worse than the party game where each person writes the next line of a story, while only seeing the previous person’s line.

- Common sense: NMT systems have very little common sense—external context and knowledge about the world. Understanding what contexts are appropriate for certain translations is important to our understanding of situations, but these contexts are often difficult to capture in their entirety.

In the rest of this article, we will explain these three flaws in more detail.

Reliability

Excuse you, neural network, that’s not appropriate.

NMT systems have no method of detecting whether what they are outputting is actually factual. Worse yet, such inaccuracy is unpredictable and inconsistent, making it difficult to automatically detect and correct. For example, NMT systems can mix up negations and omit whole chunks of information. What are the consequences of these errors?

Dan’s message was supposed to say,

“Of course, I do love you. Let’s have dinner this Friday? See you!”

But the machine betrayed him, spitting out the translation:

“Of course, I do not love you. See you!”

Quite a heartbreaking error! Certainly frustrating, yet not irreparable…

“The US did not attack the EU! Nothing to fear,”

the trusted newspaper Le Monde declared in French, yet the English world read it as:

“The US attacked the EU! Fearless.”

Imagine this mistranslation spreading across the Internet. Will the fake news go viral before we can correct it? More than frustrating—this is potentially catastrophic.

Unfortunately, fluency (which is a primary strength of NMT) can compound the problem by making inaccurate translations more believable, and thus harder to detect.

One of the greatest barriers to widespread NMT adoption today is this lack of trustworthiness. Why are these systems inaccurate? Let’s look at two big causes, and their symptoms, in detail.

Reliability problem 1: Biased data, biased translations

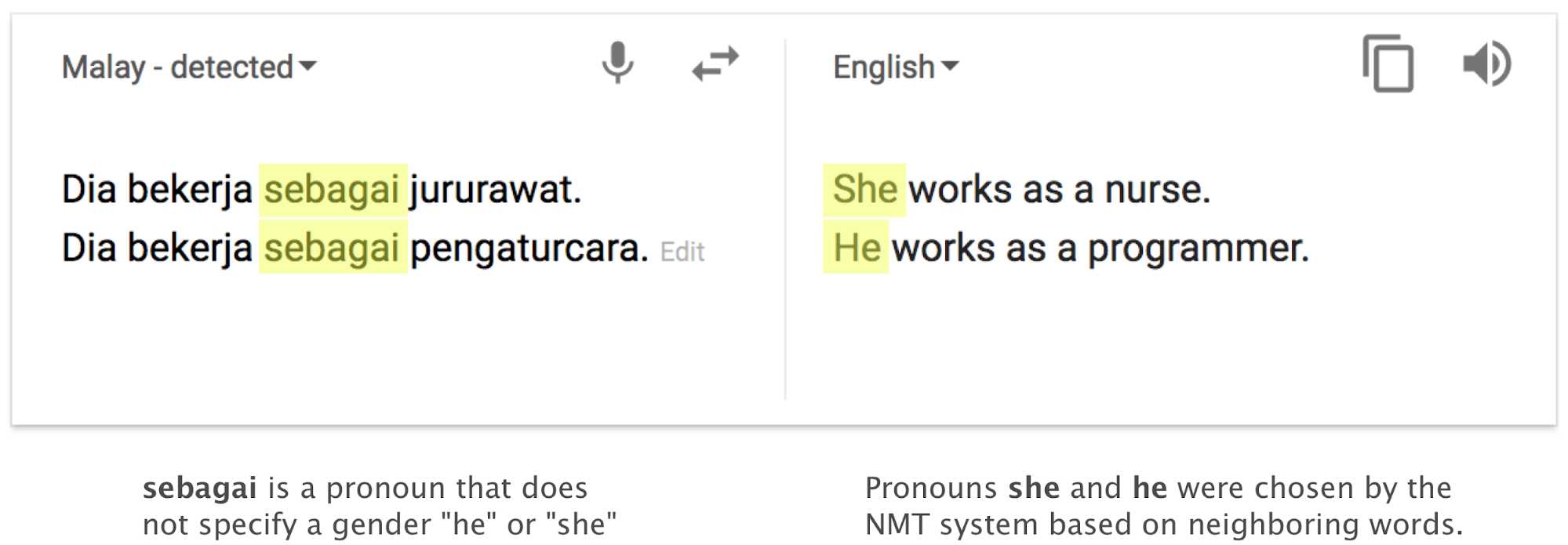

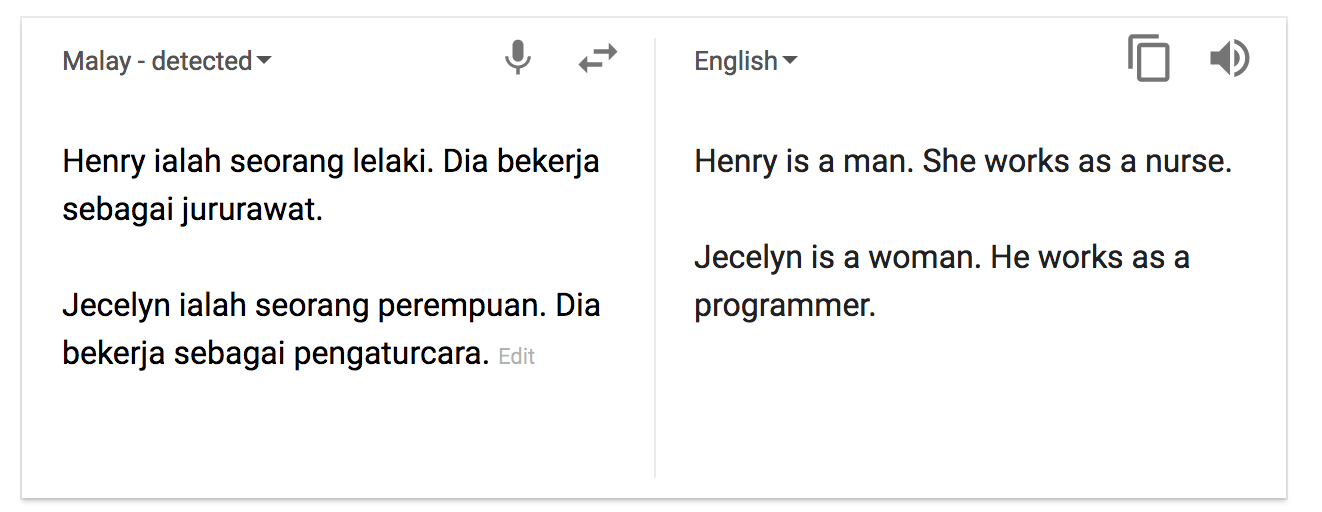

Look at this Malay-to-English example from Google Translate:

Though the original Malay text contained no gender information, the English translation has assumed that the nurse is female and the programmer is male. The NMT system has made this assumption because the training data contained more examples of female than male nurses, and more examples of male than female programmers.

This phenomenon is an unfortunate side-effect of how neural networks learn. By picking up on real-world patterns (such as the gender ratios in nursing and programming), the NMT system is inserting unfounded information into its translations. This example is particularly poignant because the translation system is compounding existing inequalities in the world. However, these kinds of errors can happen whenever the system learned a strong pattern in the training data, and might inappropriately deploy that pattern when translating. For example, if your training data was gathered in 2013 and had many examples of “US president Obama”, but no examples of “US president Trump”, your NMT system will regard the phrase “US president Trump” as highly unlikely. In the worst case, this could result in the NMT system changing “Trump” to “Obama”.

Biased data (and pronouns in particular) are a topic of great concern, as discussed by several sources [1] [2] [3]. Bias remains an open and pressing area of research.

If you are interested in learning more about the limitations of NMT, but from a more linguistic perspective, read Douglas Hofstadter’s recent article in The Atlantic.

2: Try something new, get gibberish.

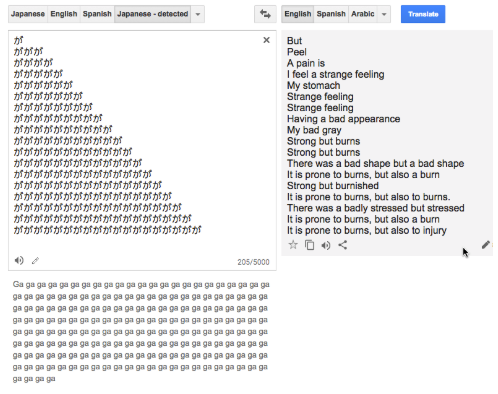

NMT systems sometimes produce nonsense. We do not quite understand the method in their madness. Here’s an example:

The number of repetitions of this Japanese character (meaning “I have a strange feeling”) produces drastically different and random phrases. Even if you cannot read Japanese, you can conclude that this output is inconsistent, nonsensical, and perhaps comical.

The reason for this phenomenon is that the repeated character input is completely different from the kind of inputs that the system was trained on. Specifically, the system never encountered such repetitious input during training, so has trouble when seeing it for the first time. As a result, in this example the English text generation system goes into autopilot, generating phrases that sound fluent in English, but have little resemblance to the Japanese input.

In general, NMT systems perform poorly when translating inputs which are drastically different from those encountered during training. This limits their ability to extend to new domains and new styles of phrasing, defaulting to gibberish when they encounter something new.

Memory

NMT systems today have another notable limitation: only translating single sentences in isolation. Yes, this means they have no idea what came before the sentence they’re translating. As humans, we read most of our sentences in context, e.g. in a document, article, story, or a sequence of messages.

Let’s consider the example of the biased pronouns for “nurse” and “programmer”. In it, the input sentences were presented with no information about the genders of the nurse and programmer. This led the NMT system to inappropriately guess the gendered pronouns, over-relying on statistical patterns that it has observed in the training data. But what if the NMT system had access to the surrounding sentences? For instance, if the previous sentence mentioned that the programmer is a woman, does the NMT system get the pronoun right?

Unfortunately not – the system is unable to use the right pronouns even when the previous sentence makes it very clear that the programmer is a woman!

What’s the reason for this severe forgetfulness? The answer is surprisingly simple: NMT systems translate one sentence at a time. This means that when we ask an NMT system to translate a document, it’s really translating each of the sentences in isolation, then sticking the translated sentences together again.

If you’re thinking that this sounds like a bad way to translate text, then you’re right – it is! Imagine attempting to translate – or to simply understand – a sentence without any context. How are you supposed to know who “he” is referring to? Or whether “that’s interesting” means something is actually interesting, a small overstatement, or a sarcastic remark? There is simply too much missing information.

So why do we train NMT systems one sentence at a time, rather than a whole document at once? The reasons are technical. Firstly, it’s difficult for a neural system to read a long document, store all that information compactly, and recall it effectively. Secondly, these systems take longer to run when the length of the input is long. Thus, we use single sentences for efficiency.

Overall, the inability to incorporate wider context is a primary barrier to NMT’s success. Almost all applications of translation require multi-sentence understanding, but in some applications – such as story translation – it’s crucial. Storytelling is as human an activity as there is, requiring a combination of creativity, intellect, and communication that sets us apart from animals. If AI translation systems can’t translate a story coherently, let alone elegantly, then can we really say that they are human-level?

Common Sense

NMT systems do not have common sense: knowledge or context about the world that would help in translating something correctly.

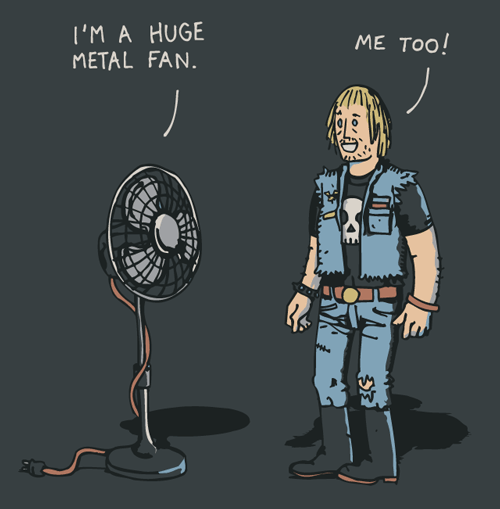

Suppose you read an article about a music concert, and send a French translation (from your NMT system) to your French-speaking friends. In the English version, the article interviews various concertgoers, including a young man who exclaims,

“I’m a huge metal fan!”

In the translation, however, this sentence becomes

“Je suis un énorme ventilateur en métal” (“I’m a large ventilator made of metal.”)

The system does not know that in this context, “metal fan” is a person who enjoys the music genre “metal”, which is more appropriate than a ventilation unit forged from metal.

This problem goes to the very beginnings of MT as a field, and has yet to be solved; we can find another example in Yehoshua Bar-Hillel highly influential 1958 paper “A Demonstration of the Nonfeasibility of Fully Automatic High Quality Translation”:

The box was in the pen.

Here, the NMT system is fooled by how to translate “pen”: is it the writing utensil or an open area?

General knowledge about the world is necessary for NMT systems to translate effectively. However, this knowledge is difficult to encode in its entirety and is not easily extractable from volumes of data. We need mechanisms to incorporate common sense and world knowledge into our neural networks.

What’s a good translation? The difficulty of evaluating NMT systems

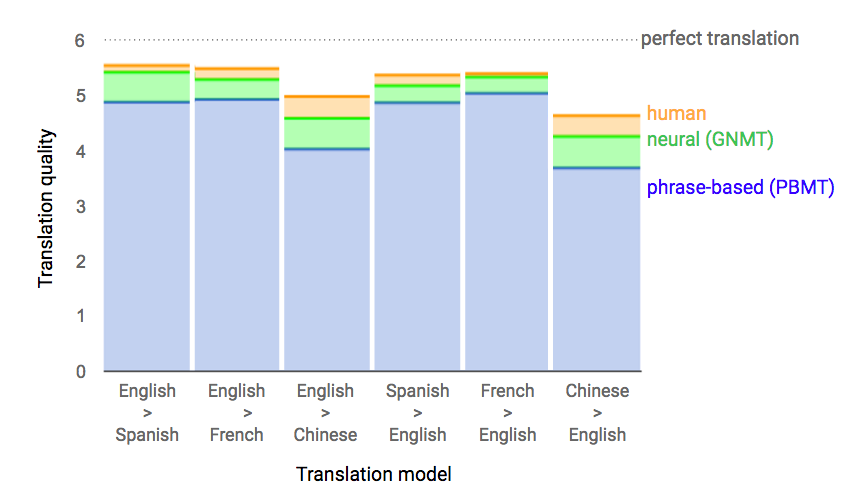

How do we measure the quality of a machine translation system? Currently, the most common way is to use the BLEU score. To calculate the BLEU score, we take the translations produced by the MT system, and compare them to the human-written translations of the same sentences. If the machine-written translations contain many words and phrases in common with the human-written translations, then the system receives a higher BLEU score.

The BLEU score is a useful rough measure of translation quality, especially for lower-performing systems. However, researchers have found that the BLEU score frequently disagrees with human judges on translation quality. This means that while the BLEU metric can help us distinguish which is best among poorly-performing systems, it is typically insufficient to evaluate better-performing systems.

Asking people to assess translation directly is a major improvement over BLEU evaluation, but is not without flaws. Most notably, there are two problems with human evaluations of AI translation:

- Human evaluation is not automatic, and is therefore expensive and slow – often requiring the time and expertise of at least one professional translator. Consequently, nearly all machine translation research uses automatic metrics like BLEU, instead of more accurate human evaluation, to measure quality.

- Human evaluation is not always consistent. At the beginning of this piece, we saw reports of NMT systems with “human-level” performance. These claims are based not only on BLEU scores, but also on human evaluations. As discussed in the papers to which those articles alluded, it is difficult to get interrater agreement from human evaluators, especially when the evaluators are not bilingual translators, but instead comparing sentences in their native tongue.

In summary, we should be wary of articles that use metrics such as BLEU as the basis of bold claims, such as “human-level” AI translators. And while human evaluation is better, it requires a lot of investment and there are caveats to be considered with regard to it as well. Moving forward, it is important to be aware of the limitations of NMT evaluation when comparing NMT systems to human translators.

We’re working on it! What does the future look like?

NMT is developing rapidly, and new advances are reported every month. New research is tackling all the problems posed above: reliability, data bias, nonsensical output, memory, common sense knowledge, and evaluation metrics. For example, Google has encouraged researchers to address bias by releasing a new set of evaluation metrics specifically for bias.

Within the past year, NMT has also seen marked improvements in effectiveness and efficiency. This comes with the introduction of new systems that no longer need to process data sequentially, e.g. from left to right, or right to left. These systems handle input sentences all at once, making it easy to parallelize data training. Thus, we can train more data in the same amount of time, and ultimately produce more effective translations. Among such successful system are Google’s Transformer and Salesforce’s Quasi-Recurrent Neural Networks.

Meanwhile, we can anticipate that the dissemination of new research will accelerate. Harvard’s OpenNMT—an open source Neural Machine Translation implementation in LuaTorch, PyTorch, and Tensorflow—is swiftly incorporating new research methods, so that others can easily build on the best systems. The new commercial system deepL, built by an ex-Google researcher, claims to have improved over Google Translate’s own translations. Meanwhile, Microsoft Translator continues to offer new features in its multilingual enterprise support. It’s a rapidly developing space, and an exciting time to see NMT evolve more powerfully under each new moon.

tl;dr

Thanks to increasingly advanced neural network techniques and large amounts of data, translations by NMT systems can often sound fluent and human-like. But despite this seemingly impressive state of affairs, NMT is still far from reliable. We can translate single sentences, but not longer pieces of text. We can translate well enough for humans to get the gist, but not reliably enough for applications where accuracy is crucial (such as diplomacy), and not artistically enough for applications where elegance is important (such as literature). Still, the neural era has enabled machine translation to come a long way in just a few years, and we’re still rapidly making significant advances. The field is undergoing large improvements, as systems get faster, more effective, and more accessible to anyone who wants to run them.