Autonomous Driving, Both Close and Far from Ubiquity

Autonomous vehicle technology has made huge advances in the last couple of years — what's left to solve? A whole lot.

Image credit: (source)

Videos like the one above make it obvious that self driving technology has come a long ways in the last couple of years. Waymo, Tesla, Lyft, and many others are actively testing self driving cars with promising results, and there is an un-ending stream of news about the tech’s advances and commercial interest in it.

So, where are all the self driving taxis? The truth is this: impressive though it may seem, self driving car technology is still far from ready to take over driving. Demos of cars driving autonomously for long stretches are routinely released by companies spending billions of dollars on it, but, these demos hide the fact multiple enormous challenges remain before our cars can drive us around sans human help. In particular, there are three major largely unsolved challenges:

- handling the large variety of everyday occurrences

- the possibility of intentional foul play

- ethical and policy decisions

Though they may seem unassuming, these are huge hurdles that are beyond today’s state of the art data-driven AI approaches (no matter what companies such as Nvidia or Drive.ai claim). Getting to where we are has not been easy, and the good news is that the industry is aware of these challenges and are actively pursuing solutions. Let’s review where we are, how we got here, and where we expect to go.

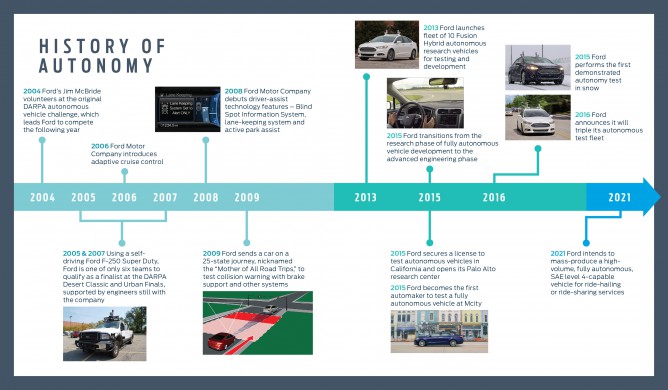

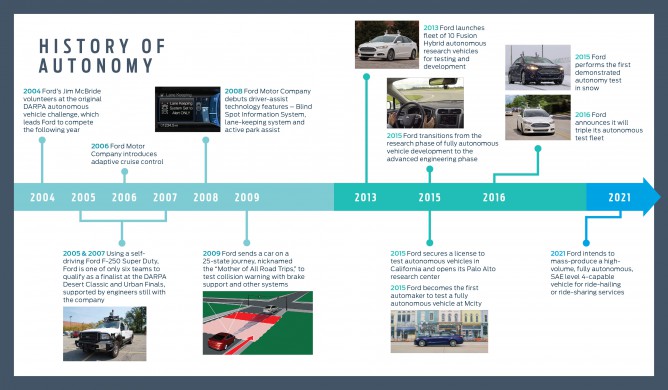

A (Very) Brief History of Autonomous Driving

One of the first conceptions of autonomous driving came from da Vinci’s self-propelled cart: a system of compressed springs and preset steering that allows a cart to move on its own without human assistance. This device wasn’t practical though, and required human or animal labor for locomotion. This meant that serious attempts at automation only emerged much later. The advent of today’s autonomous vehicle systems required the development of a set of largely complementary technologies.

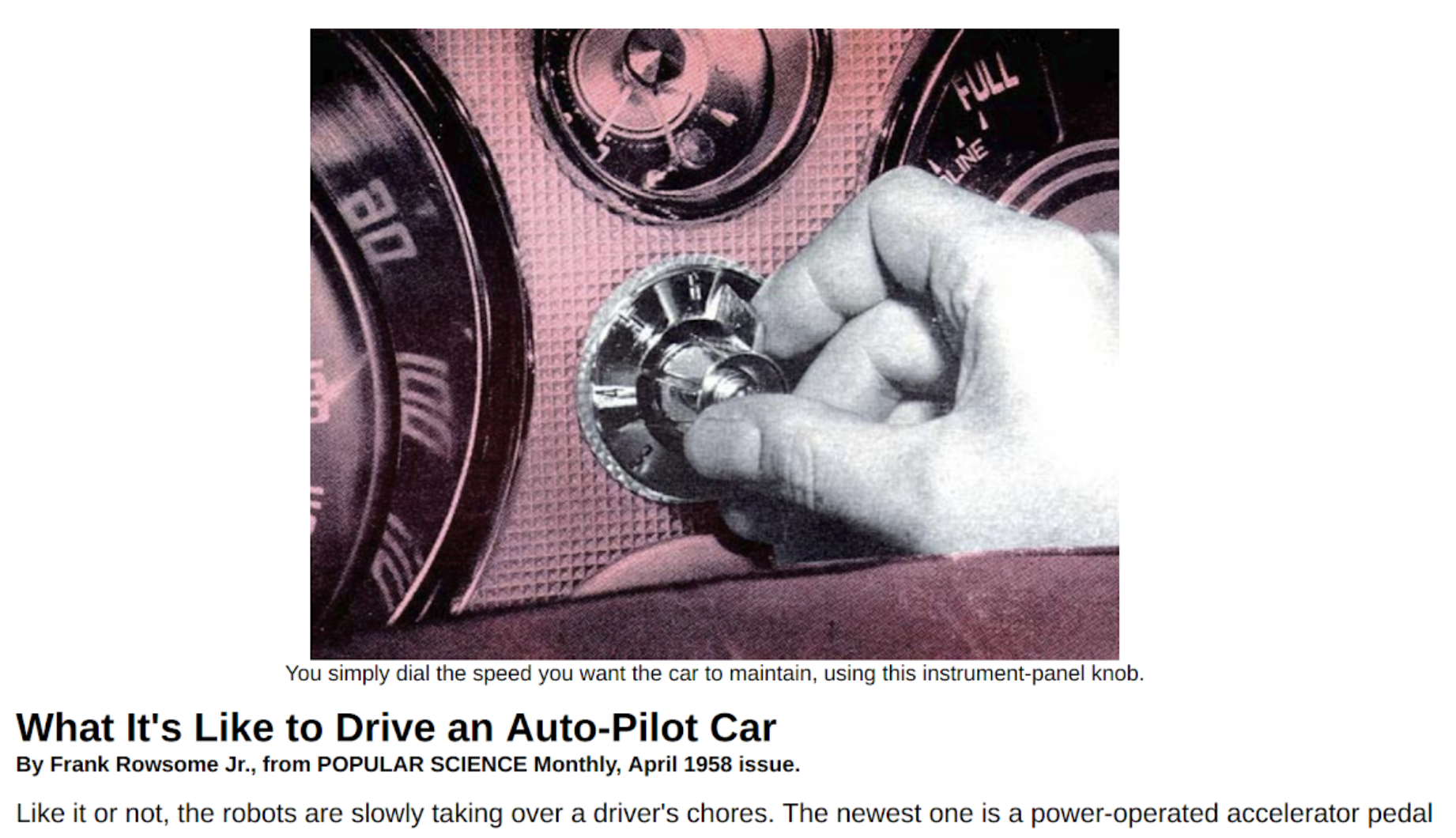

As is often the case, the military proved to be an excellent catalyst, starting with simple un-guided weapons in the late 1800s like the torpedo. However, it was not until the development of sensors such as radar and sonar in the early 20th century that true self-steering or “homing” was achieved. But it was not all about military R&D - rapid industrialization and innovation in the U.S. heralded the prevalence of private automobiles and the pervasiveness of air travel. Such rapid progress in transportation created nuisances that were solved by automated control - cruise control and the autopilot. These are two technologies that allowed mechanical devices to maintain a steady state without human input. Drivers no longer needed to keep their foot on the gas pedal for hours on end, and pilots could finally stretch while checking the weather or monitoring other flight systems.

Around the same time, the miniaturization of electronics and the commercialization of radio control from the military led to the notion of remote control. While a human was always nearby to intervene should the machine fail to act or make a mistake, the physical separation provided by remote control allowed for more risk, be it running an RC car into a wall or delivering an explosive warhead via missile. The biggest motivation for autonomy finally arrived when humans decided to reach for the final frontier - working in space. How could humans control a rover on another planet when every radio instruction took multiple seconds to register? Enter the first practical self-driving vehicle (1961): the Stanford cart, a scrappy wagon on wheels that used a monochrome camera and could only follow a white line for about 50 feet before losing its way. The politics and optics of sending humans to space took precedence in the 20th century, and the cart was abandoned. But AI was then still in its infancy (the term having only been coined in 1956), and researchers rapidly made progress and soon moved on to more sophisticated robotics research.

In the eyes of the average driver, the first modern autonomous vehicle didn’t materialize until 1987. Ernst Dickmanns, often compared to the Wright brothers, and his research group at University Bundeewehr Munich (UniBW) built a robot car that could discern other cars and even pass them. At about the same time, Dean Pomerleau led a project at Carnegie Mellon University called ALVINN (Autonomous Land Vehicle In a Neural Network which aimed to use modern AI to drive a car). As recently covered by The Verge, the team’s use of a neural network was impressively prescient:

“The result of eight years of military-funded research at CMU’s robotics institute, ALVINN could be considered the forefather of today’s self-driving cars, Cameron told me in an email. “Why? The approach ALVINN took was using a neural network to drive the car, which was absolutely novel for the time and is quickly becoming an increasingly popular approach with self-driving car efforts,” Cameron said.”

These advances led to a renaissance of funding for self-driving technology, starting with the 1987-1995 near billion-dollar PROMETHEUS Project in Europe and culminating in the 2005 DARPA autonomous vehicle challenge, an ambitious program that spawned the many self-driving initiatives we see today. Many of the key researchers that participated in the DARPA race, such as the winning team’s Sebastian Thrun, were soon scooped up by companies like Google eager to get an early start in the race.

So, Where Are We Today, Exactly?

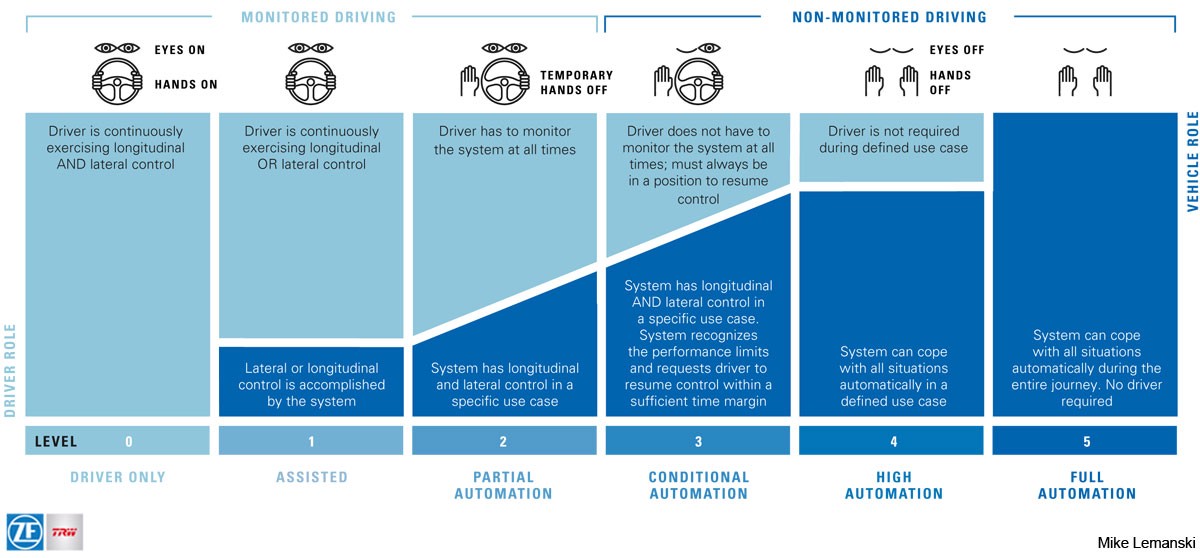

Only a decade ago, the thought of never having to drive again seemed like a page from a science fiction novel. Now, autonomous vehicles are very much part of the Zeitgeist. At automotive trade shows and gadget conventions alike, self-driving cars steal the spotlight through a frenzy of live demos, partnerships, and product announcements. There’s a lot of hype, but what does autonomy actually mean when it comes to driving? Industry experts have broadly defined the following categories:

- Level 1: Driver assistance. The car helps the driver, but the driver is fully in charge – for instance, adaptive cruise control where the car automatically slows down if it approaches another car too closely.

- Level 2: Partial automation. The car can help with steering and acceleration. It might match the speed of traffic and stay in lane, but drivers need to keep their hands on the steering wheel.

- Level 3: Conditional automation. In the right conditions, the car can mostly drive itself and lets the driver know when a situation arises that it can’t handle. The main difference compared to the previous level is that the car actively monitors its surroundings using a suite of sensors (e.g. lidar). Many consider Tesla Autopilot to be between level 2 and 3.

- Level 4: High automation. Barring unusual circumstances, such as poor weather, the car drives itself. Waymo’s now-retired Firefly, a pod without any pedals or a steering wheel, is one such system; it was restricted to a top speed of 25 mph.

- Level 5: Full automation. All the humans are passengers, and there isn’t even a steering wheel. This is the holy grail of transportion automation.

So, how good is modern self driving tech? What results do we already have? Here’s a quick breakdown:

- Most passenger cars come with some form of driver assistance (level 1)

- Expensive luxury cars from almost every major brand are rolling out with partial autonomy (level 2), whether it’s Tesla’s Autopilot, GM’s Super Cruise (coming out on select Cadillacs), Mercedes-Benz Distronic Plus, or Nissan ProPilot Assist.

- Many of these technologies are approaching conditional autonomy (level 3) by supporting specific scenarios, such as lane changes, but are unable to broadly take the place of a human driver.

- Other teams have more ambitious goals. Waymo, the self-driving division of Google’s parent company Alphabet, is holding out on immediate commercialization in favor of rolling out a fleet of highly autonomous (level 4) minivans.

Each of these major self-driving car initiatives have announced that their prototypes have driven millions of miles. Some of them are public (e.g. Tesla) while others are rolling out as this piece is being written (e.g. Drive.AI). The progress is obvious. However, there are many more millions of miles to go before truly autonomous driving truly crosses into the mainstream. Major automakers predict turning the proverbial self-driving corner no sooner than 2020, and AI experts like Rodney Brooks (a Professor of Robotics (emeritus) from MIT) consistently predict that we are still decades away. What is holding back the self-driving revolution?

Basically Everything That Happens is a Challenge

Autonomous vehicles seem to be just around the corner, but the truth is that currently even the most commonplace situations are still hard for these technologies to get right. Michael Benisch, Director of Autonomy at Lyft’s self-driving car project Level 5, recently gave a fascinating talk at Stanford about the challenges ahead for deploying autonomous vehicles (AVs). He talked about how everyday occurrences on the road still pose a big challenge, and in particular highlighted three categories of challenges: environment conditions, spontaneous external inputs, and situations requiring inference. However, he also mentioned that many mitigation strategies are being developed and implemented to address these challenges, including redundant systems, simulation-based integration tests, and real-world tests on private roads.

Environmental conditions such as heavy rain, snow, or sleet are common in many non-California locations. Driving in these conditions are difficult for humans, let alone computers, and require self driving cars to be more robust to changes in temperature and visibility. Things get a bit more interesting with “spontaneous external inputs”. Examples include simple events like car doors being opened, children running into the road after a ball, or bikers swerving into the car lane. Self driving cars are still largely unable to process and react to these situations in an appropriate manner. Rodney Brooks expertly discusses this topic in his essay “Edge Cases for Self Driving Cars”:

In my local one-way streets the only thing to do if a car or other vehicle is stopped in the travel lane is to wait for it to move on. There is no way to get past it while it stays where it is. The question is whether to toot the horn or not at a stopped vehicle. Why would it be stopped? It could be a Lyft or an Uber waiting for a person to come out of their house or condominium. A little soft toot will often get cooperation and they will try to find a place a bit further up the street to pull over. A loud toot, however, might cause some ire and they will just sit there. And if it is a regular taxi service then no amount of gentleness or harshness will do any good at all. “Screw you” is the default position.

Lastly, many situations require a level of inference when driving. For example, if a ball rolls into the road, human drivers may look out for children coming into the road to retrieve the ball. Another example is when a neighboring car “disappears” behind a large truck. The car has obviously not disappeared, but will come back into view when the truck passes. Us fleshy humans manage to handle these situations with relative ease because we are able to predict how our environment will change and adapt as needed. Autonomous vehicles lack this level of reasoning. A New York times article, 5 Things That Give Self-Driving Cars Headaches, discusses other everyday situations that AVs struggle with such as unpredictable humans, bad roads, and detours.

Fully automated cars don’t drink and drive, fall asleep at the wheel, text, talk on the phone or put on makeup while driving…But there is something self-driving cars do not yet deal with very well – the unexpected.

Solutions

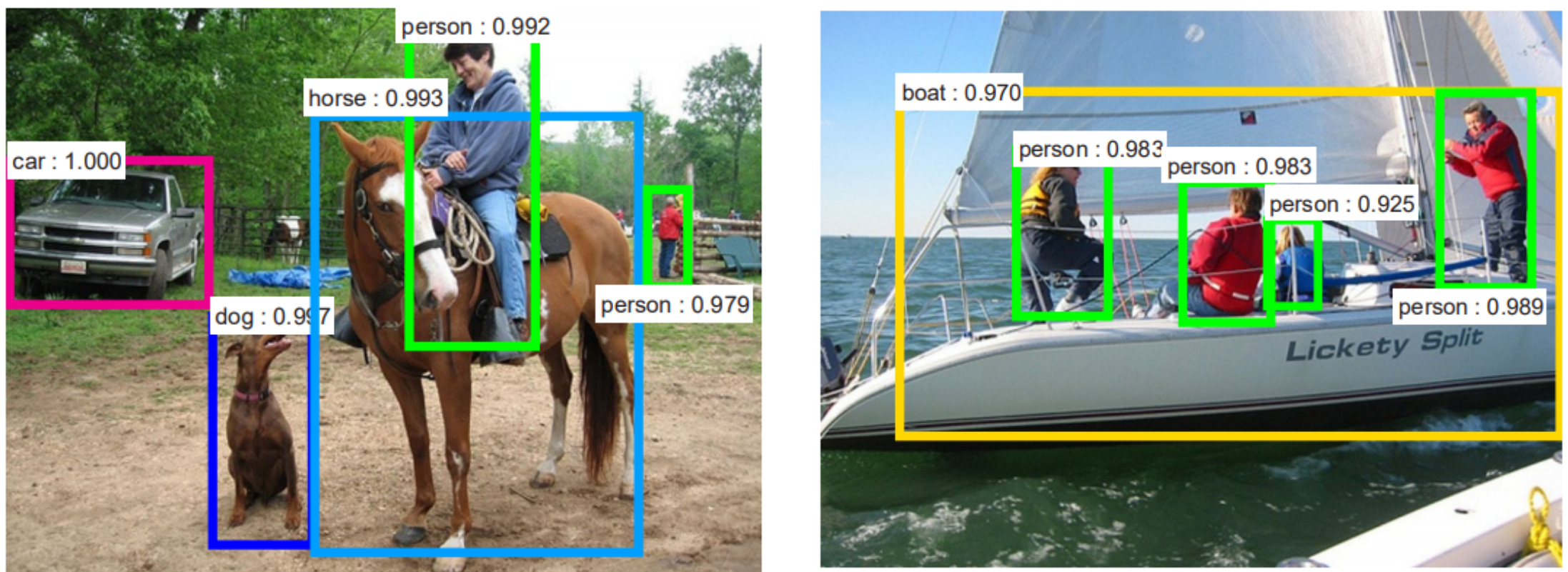

Modern autonomous vehicles are fundamentally enabled by Computer Vision, but the technology is far from perfect. Being able to understand and analyze the environment through sight is no trivial task.

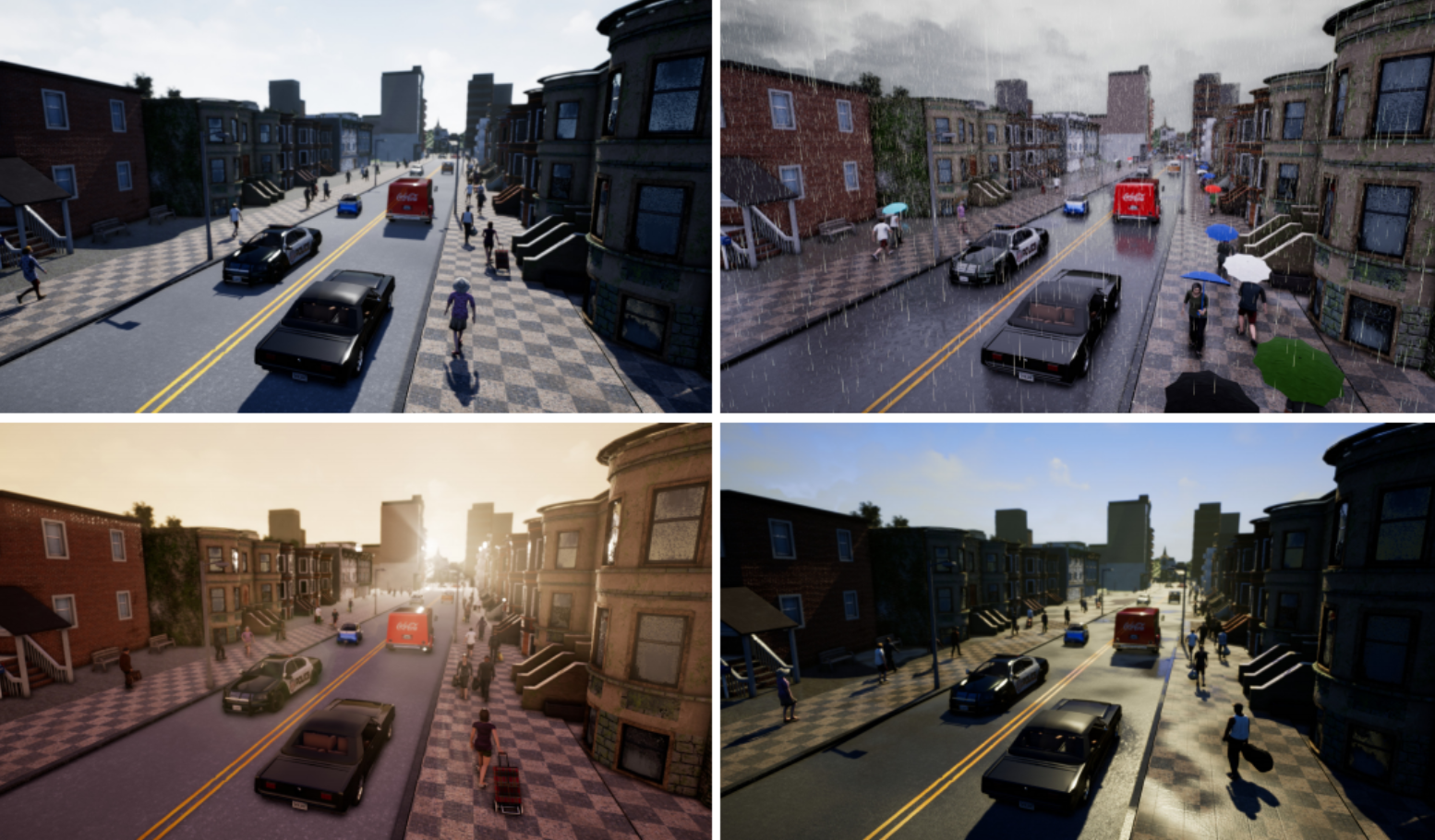

People may be able to identify and name different objects in an image (Source Source), but understanding global relationships between objects and being robust to malicious sites are just a few tasks that need huge improvements before autonomous vehicles can be deployed. Approaches to tackling these issues include redundancy, simulators, and driving practice in the real world. An important technique for ensuring safety is using simulators. Prototyping multiple car designs becomes expensive and makes it difficult to manufacture and test multiple designs and algorithms. This has given rise to startups that create self-driving car simulators, such as CARLA and Nomoko, that are used to design and test cars before spending millions of dollars to even manufacture a prototype. Simulators are also used to generate data to train the car. Millions of crash scenarios and weather conditions are generated and tested digitally without any need to drive through Minnesota in February.

But of course, testing in simulation alone is not enough - at some point, we need to verify that the technology works in the real world. Private road testing facilities provide spaces dedicated for AV testing. Lyft uses GoMentum to test their self driving cars. A technique called geofencing is used to blacklist certain areas and routes where AVs are not able to drive. This includes areas with traffic circles and unprotected left turns, for example. The mitigation strategies mentioned so far are being used in an industry setting. Creating defenses to the adversarial examples mentioned previously is an active research problem in academia (Source Source Source). Even with these defenses, performance of the machine learning model on these malicious images is poor.

Bad Guys are a Problem Too

So far, these scenarios occur naturally and without anyone trying to intentionally confuse the AV. However, there are many situations where a malicious actor could intentionally tamper with the car. Car hacking is more real that you may expect. At DEFCON, the world’s largest hacker conference, there is a Car Hacking Village where hackers find and exploit vulnerabilities in vehicles. In 2015, Charlie Miller & Chris Valasek walked through how a remote code execution exploit can be done on a vehicle. As sophisticated as this exploit may seem, simpler and equally frightening attacks can be done. For example, an attacker can physically tamper with the car’s sensors by blocking them from picking up signals. Furthermore, attacks are not limited to physically altering the sensors. Simply shining a light into the sensor from afar can significantly throw off the computer vision used by the AV. More sophisticated attacks on the machine learning models can also be performed; Google researchers have devised a method of generating maliciously designed stickers, or adversarial patches, that can trick the vision system into incorrectly interpreting what it sees.

Autonomous vehicles that leverage cutting edge computer vision technology can reliably misinterpret road signs if these stickers are placed on them. Such methods for fooling machine learning models are called adversarial examples. Although the idea of such attacks only came around 4 years ago, there is now an entire line of research that focuses on developing new ways to create them.

Ethical & Policy Considerations

Even if the current challenges facing AVs are overcome, there are still numerous ethical considerations that need to be discussed before AVs can become commonplace. These considerations are still open questions. Who should be made responsible for decisions that autonomous vehicles make? For example, should AVs prioritize the life of people inside the car or people outside? Would the life of a senior citizen have more or less value than the life of a young adult? Humans already make these kinds of decisions when driving so should AVs mimic human decisions? Furthermore, who is to make the decisions? Three parties come to mind when assigning the decision-making responsibility of AVs: individuals, companies making AVs, or governments. Should individuals be given the option to choose how much the car favors them when in a tough situation? Or should companies and/or governments decide? There may also be situations where an accident is unavoidable for a human, but could have been avoided by an autonomous vehicle. What should happen when an AV could have prevented an accident in this situation, but didn’t?

It is evident that when it comes to public policy and ethical considerations for AVs, there are more questions than answers. Innovations like AVs have ethical consequences and their success is highly dependent on public policy.

Whether they require drivers or not, AVs require permits to be be used on public roads. Each state has their own set of regulations when it comes to AVs. In California, the Department of Motor Vehicles has three different permit options: a testing permit (requires a driver in the car), a driverless testing permit, and a deployment permit. Here is a list of some parts of the regulations on AVs:

-

Autonomous vehicles must be tested in controlled conditions that closely simulate the Operational Design Domain they will be driving in. An Operational Design Domain is the domain in which the AV is designed to properly operate. Properties of a domain involve the geographic area, roadway type, speed range, and environmental conditions, among other factors.

-

The manufacturer must continuously monitor the status of the vehicle via a 2-way communication link.

-

A process must be in place for communication between parties involved in an accident, like between law enforcement and the manufacturer.

-

A driverless autonomous vehicle must meet the description of a level 4 or level 5 automated driving system under SAE International’s Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles.

You can read more about California’s AV rules and regulations here and here.

In addition to state laws, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has recommended guidelines for manufacturers and policy makers. The NHTSA created A Vision for Safety to promote the safe deployment of autonomous vehicles. The report outlines best safety practices and design considerations such as vehicle cyber security, human machine interface, and crashworthiness, to name a few. It also encourages entities testing these vehicles to disclose safety assessments in their systems to harness trust. Lastly, the report also suggests safety related legislation that states should adopt regarding AVs. The report can be found here.

When will the driver become the driven?

The transition from human-driven cars to fully autonomous self driving cars will not happen quickly. As with the transition from horse-drawn carriages to cars in the early nineteen hundreds, there are many changes such as the current transportation infrastructure, vehicle ownership model, and fueling procedure among other factors that need to be dealt with before self driving cars become common place. Many other small changes will be put into place incrementally. Road structure may change to accomodate self driving cars in a separate lane. Buildings may have special locations for self driving cars to pick up and drop off their riders. It is likely that the first step, which is already starting to happen, will be to deploy fully autonomous vehicles in geofenced areas under certain weather conditions and time of day.

Rodney Brooks has predicted some major milestones in the wide deployment of AVs. He predicts that the first driverless taxi service in a major city will be in effect by 2022 and the first driverless car packaging delivery service in restricted geographies will be in effect by 2023. A publication by EY, Deploying autonomous vehicles (AVs): The case for autonomous vehicles, predicts that connected AV networks, on-demand mobility, and customizable AVs will be available more than 20 years from now.

So, let’s summarize: AV tech has come a long way, but still has a long way to go – we shall soon see limited uses of self driving in major cities, but you should not expect to throw your drivers license away for a few decades yet. Still, cars are already autonomously driving around our streets, and that we have achieved that much is already amazing.