Sophia the Robot, More Marketing Machine Than AI Marvel

First robot to be granted a citizenship and a visa, Sophia does not have much to offer in terms of technology

Image credit: Photo by ITU Pictures on Flickr

What Happened

In October of 2018, the humanoid robot Sophia (shown above) from the Hong Kong-based firm Hanson was granted an electronic visa by the government of Azerbaijan. The electronic nature of the visa was not incidental; this PR event was organized by the new e-services branch of the government of Azerbaijan to showcase its one-stop electronic services delivery agencies.

This sort of headline-drawing event is not new for Sophia. Most notably, Saudia Arabia made Sophia the first robot ever to be granted citizenship in 2017, and Sophia was once made to say “I will destroy all humans”:

As pointed out in a Wired piece “The agony of Sophia, the world’s first robot citizen condemned to a lifeless career in marketing”, Sophia has also been used to market a wide variety of things such as “tourism in Abu Dhabi, a smartphone, a Channel 4 show, and a credit card.” This intensive PR and multitudes of interviews have at times created the impression that Sophia represents the state of the art in robotics and AI, or that Sophia gets the human treatment because of being almost human; on Jimmy Fallon’s The Tonight Show Hanson went as far as saying that Sophia is “basically alive”.

The Reactions

Despite the large amount of coverage that every one of these events attracts, most reactions to Sophia tend to be critical and tend to include adjectives like “weird” and “creepy”.

Some articles in response to Sophia being given citizenship focused on the consequences of giving human rights to a robot. They were mostly negative, pointing out that AI is far from being advanced enough to deserve rights that many human beings are still denied and that public trust would be eroded by marketing ploys overselling the current state of the technology:

- After she was granted Saudi citizenship, many outlets were prompt to point out that the gendered robot had been given better human rights than Saudi women, since Sophia hadn’t been required to wear a headscarf as is legally mandatory for human women. Quartz went as far as saying that Sophia’s latest claim to fame was eroding human rights, as it is part of a trend in personifying robots and giving away rights “for cheap PR stunts”. This opinion has also been expressed by some AI experts, such as Nvidia’s director of machine learning research Anima Anandkumar:

Makes me so angry that they go on to declare this puppet a citizen while robbing actual women of human rights and freedom. The contrast is appalling

— Anima Anandkumar (@AnimaAnandkumar) November 21, 2018

- Business Insider ran a complete breakdown of the implications of giving citizenship to a robot. They listed the many issues that would come with trying to define how the rights given to Sophia should be implemented, especially in situations involving actual humans.

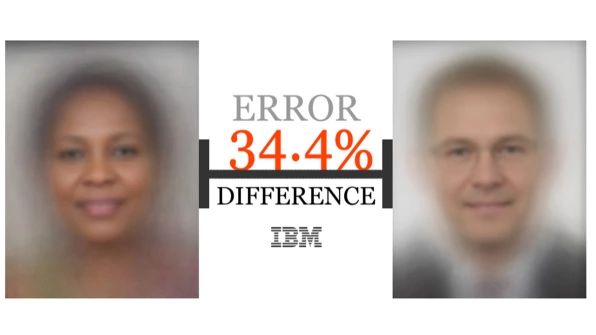

Coverage of Sophia has also drawn heated reactions from experts in the field, who express worry about the media’s exaggerations about the robot and its abilities. The difference in perception between the general public (seeing Sophia as a marvel of engineering and intelligent software) and the scientists (calling Sophia a puppet) is particularly striking:

- In one of the least critical articles, Forbes described the interaction between Azerbaijan’s president Ilham Aliyev and Sophia as “AI humanoid […] speaks with president”. Rodney Brooks, the roboticist, pointed out that the title was misleading, comparing Sophia to kabuki theater:

This is completely bogus and a total sham. Shame on Forbes for publishing kabuki as reality. https://t.co/y88wlPL2Pa

— Rodney Brooks (@rodneyabrooks) October 27, 2018

- In response to the author of the Forbes piece questioning whether he was indeed wrong, Benedict Evans (a partner at the technologically focused venture capital company Andreessen Horowitz) equated Sophia to a “tape recorder with a rubber head on top”:

It’s a tape recorder with a rubber head on top. Calling this ‘her’ or talking in terms of conversations is not a good description.

— Benedict Evans (@benedictevans) October 27, 2018

- Which was further supported by AI researcher Stephen Merity:

I strongly agree with @benedictevans. Ask any practitioner in the space and they'll angrily rant that Sophia and the media's portrayal is everything wrong in terms of hyping AI that doesn't exist and ignoring the massive benefits and potential disasters of AI in the real world.

— Smerity (@Smerity) October 29, 2018

- Yann LeCun, Chief Artificial Intelligence Scientist at Facebook AI Research, called Sophia “complete bullsh*t” and expressed concern at the way the public perceived the humanoid robot:

This is to AI as prestidigitation is to real magic.

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) January 4, 2018

Perhaps we should call this "Cargo Cult AI" or "Potemkin AI" or "Wizard-of-Oz AI".

In other words, it's complete bullsh*t (pardon my French).

Tech Insider: you are complicit in this scam. https://t.co/zhUE4V2PSR

- After a tweet that claimed Sophia was a “a bit hurt” by the comments, Lecun expanded and doubled down on the criticism:

More BS from the (human) puppeteers behind Sophia. Many of the comments would be good fun if they didn't reveal the...

Posted by Yann LeCun on Tuesday, January 16, 2018

Such comments have in turn led to coverage focusing on whether it is actually unethical for Hanson to misrepresent how advanced the AI of Sophia is, such as with the Verge piece “Facebook’s head of AI really hates Sophia the robot (and with good reason)” and most recently the Forbes piece “Mama Mia It’s Sophia: A Show Robot Or Dangerous Platform To Mislead?”. In response to the latter article, Yann LeCun doubled down on calling the misleading representation of Sophia “total bullsh*t”:

Nice article by Noel Sharkey in Forbes about the history of "show robots". His point: Sophia from Hanson Robotics is a...

Posted by Yann LeCun on Tuesday, November 20, 2018

On one hand, Hanson seems to have been masterfully leveraging the public’s fascination for “almost human” robots; on the other hand, each of their claims draws ire from the people who have sufficient background to evaluate them.

Our Perspective

There are three main approaches to the issue of making humanoid robots seem “alive”. You can make them look like human beings, you can look for life-like dynamics, or you can exploit the social biases of the viewers. With this last approach, lifelikeness is in the eye of the beholder: we give robots human names (eg Sophia, Alexa), human gendered attributes (makeup, feminine clothing), talk about them using human pronouns (as I have been doing in this article), or grant them human rights like citizenship and visas. This is clearly the approach taken by Hanson robotics. From Sophia’s clothing to the pre-programmed speeches about “her father” or “her feelings” to the human-like facial expressions and rubber skin, each of Sophia’s attributes and carefully staged appearances is a theatrical performance where the puppet master and the viewers do most of the work needed to bring the robot to “life”.

Although Hanson claims that Sophia “can” process video and audio data, it is unclear whether the robot really does process anything during public events: Hanson admits that Sophia’s speeches are usually pre-programmed. Quartz ran a feature showing that at full capacity, the software was a run-of-the-mill chatbot platform with basic object recognition features and a search engine. For all of of Sophia’s most impressive PR stunts, it does not “speak” any more than the radio receiver in your phone, and it only moves as much as the hidden human operator who holds the joysticks wants. And of course, Sophia’s twitter account is entirely run by human beings.

There is no issue with enjoying the performance for what it is. The problems appear when commentators forget that this is make-believe and write things like “Sophia speaks with president”, when people ask questions as if Sophia has human-liked agency, and when Sophia is presented as technologically advanced to the detriment of real advances in technology. In fact, Tony Belpaeme (Professor in Robotics at Ghent University, Belgium and Plymouth University, UK) recently shared a concerning story about unreasonable expectations brought about by Sophia:

I had an EU project reviewer express disappointment in our slow research progress, as the Sophia bot clearly showed that the technical challenges we were still struggling with were solved.

— Tony Belpaeme (@TonyBelpaeme) November 18, 2018

Which in turn caused Rodney Brooks to once again deride Sophia as a ‘sham demo’:

This is why I call BS on sham demos and on fear mongers who proclaim that human level and even super human level AI is just around the corner. https://t.co/FunhR25BYN

— Rodney Brooks (@rodneyabrooks) November 18, 2018

It is Hanson robotics’ responsibility to be clear about how much of Sophia’s appearances is staged, and for that they must find other incentives than benefitting from opaque PR stunts. Claiming that Sophia “is basically alive” as Hanson did on Jimmy Fallon’s show is a bald-faced lie, and an irresponsible attempt at grabbing the public’s imagination. It is the responsibility of commentators to bring honest reporting to the public by highlighting what Sophia is and what she is not, even if their incentives are biased toward ad revenues and clickbait. Finally, as consumers of news stories, it is our responsibility to refrain from giving uncritical visibility to outrageous headlines, to be sceptical of what we do not know, and to call out exaggerations in the media.

TLDR

The humanoid robot Sophia is less technologically advanced than most existing robots and is mostly used as a puppet, but its creators benefit from falsely claiming that it is almost human. Through carefully staged PR stunts, they capture the public imagination in questionable ways.