DeepMind’s AlphaFold 2—An Impressive Advance With Hyperbolic Coverage

The results are encouraging, but journalist ebullience belies the difficulties ahead.

Image credit: DeepMind

Summary

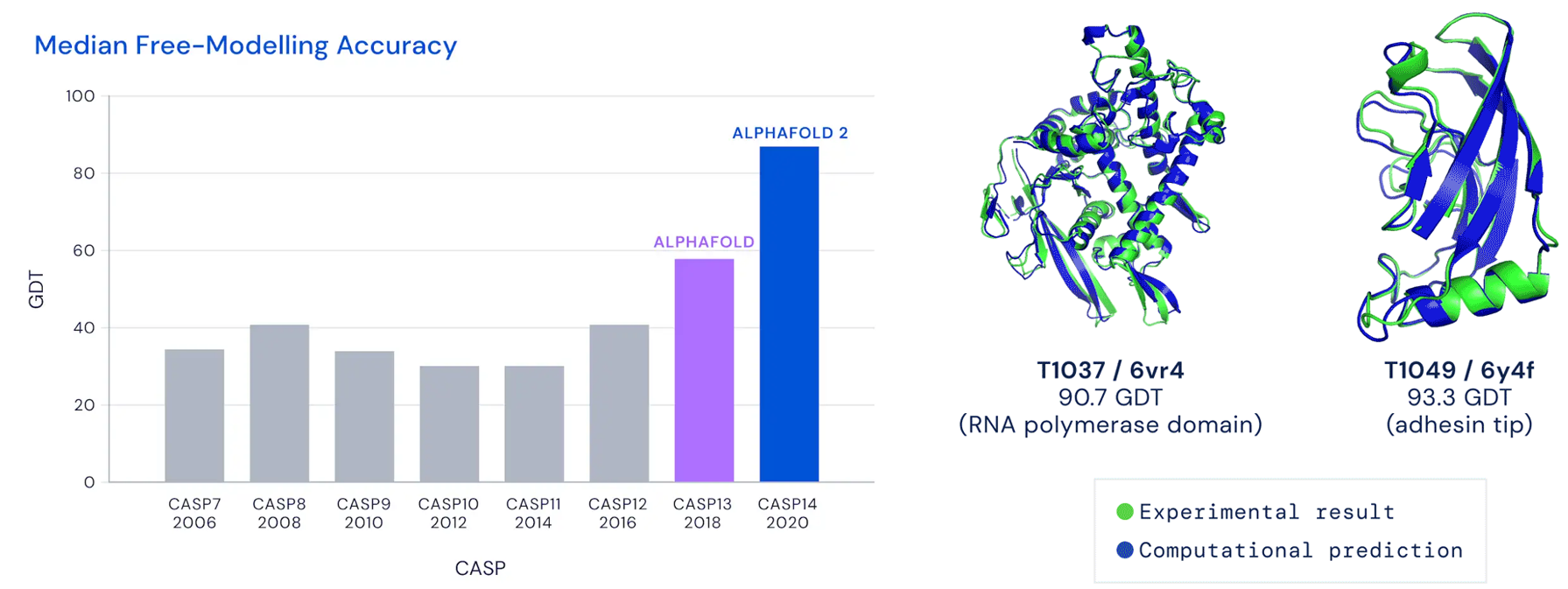

- DeepMind’s AlphaFold 2, a deep-learning model that predicts protein structures, achieved significant improvements over other methods in the biannual CAPS protein folding prediction competition.

- The improvements are so large that some claim protein folding is a solved problem. However, while almost all applaud the impressive advancement, many note the caveats and limitations of AlphaFold 2 in both the problem of protein folding and downstream uses in biology.

- After weighing the opinions of many experts, we take the view that while AlphaFold 2 should be celebrated, it is still just one step (though a big one!), and will not significantly advance practical applications like drug discovery.

What Happened

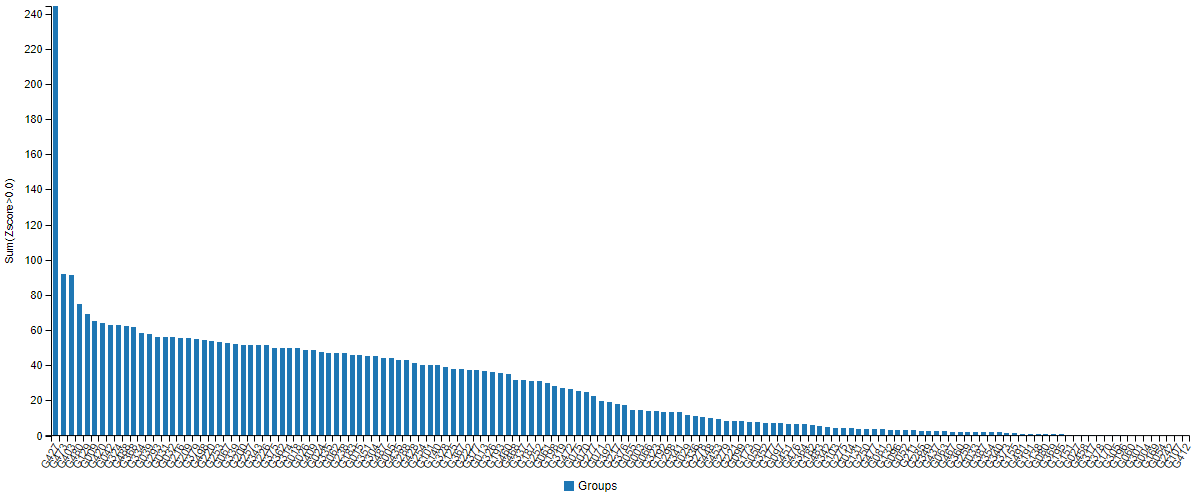

On the last day of November 2020, Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP), a biennial challenge for computational biologists on the problem of “protein folding”, released its results, showing DeepMind’s AI-driven Alphafold 2 outperforming its competitors by a large margin. The pace of Alphafold’s improvement came as a shock to many researchers and mainstream media publications, who heralded the development as a game-changer for biology. Others acknowledged the uses of the tool, but cautioned that there were many more challenges in the protein-folding prediction space that may warrant a tempering of expectations, let alone the broader field of biology.

In the world of proteins, form determines function. Thus, the ability to look forward and predict protein structures would help all kinds of biology subfields, from the more basic science work to drug discovery. Historically, attempts to model proteins have failed due to exponentially increasing computing costs, but specialized computational hardware appears well-equipped to address this issue.

Alphafold made some waves with its 2018 CASP win, but the media coverage was decidedly more muted then. The pace of Alphafold’s 2020 improvement on top of its own success in 2018 was shocking for many experts, who felt that a solution to the 50-year old protein-solving problem was finally in sight. One important note is that AlphaFold 2, like other methods submitted to CASP, doesn’t actually model how proteins fold - it just predicts the final structure of the protein after it has folded.

There are a number of quality blog posts that explain protein folding and AlphaFold 2. Jason Crawford at Roots of Progress gives an accessible review of protein folding in What is the “protein folding problem”? A brief explanation. It is also summarized in this excellent Twitter thread:

Today Google @DeepMind announced that their deep learning system AlphaFold has achieved unprecedented levels of accuracy on the “protein folding problem”, a grand challenge problem in computational biochemistry.

— Jason Crawford (@jasoncrawford) December 1, 2020

What is this problem, and why is it hard?https://t.co/OjbP3RBPEi

For a more technical explanation of AlphaFold 2 itself, we refer readers to the blog posts by Mohammed AlQuraishi and Carlos Outeiral. In summary, DeepMind trained a neural network model on 170k known protein structures in the publicly available Protein Data Bank dataset (PDB). In addition to its many novel architecture designs, one important aspect of this neural network seems to be its use of attention mechanisms, a similar kind of architecture used by recent state-of-the-art language models like GPT-3.

An attention-based technique was used, which has shown promise across ML in language/vision/etc. This allows for efficient learning (ie capturing relations between elements) and uncovering broader principles: https://t.co/hKTcb5mTkr

— Ali Madani (@thisismadani) November 30, 2020

Very exciting results this week from AlphaFold in CASP14. An incredible and inspiring achievement by the DeepMind team. Many new possibilities.

— Alex Rives (@alexrives) December 4, 2020

*Attention* mechanism is key to the result. Interestingly we find the exact same in our work on *unsupervised* learning for proteins.

The Reactions

From the Press

The press was very optimistic about AlphaFold 2’s progress in protein folding and its broader implications in biology and beyond, with headlines like:

- Nature: ‘It will change everything’: DeepMind’s AI makes gigantic leap in solving protein structures

- Science: ‘The game has changed.’ AI triumphs at solving protein structures

- MIT Tech Review: DeepMind’s protein-folding AI has solved a 50-year-old grand challenge of biology

- IEEE Spectrum: AlphaFold Proves That AI Can Crack Fundamental Scientific Problems

From the Experts

Carlos Outeiral, Computational Biology research scientist at Oxford, also highlighted the “astoundingly” impressive results of AlphaFold 2, in the post CASP14: what Google DeepMind’s AlphaFold 2 really achieved, and what it means for protein folding, biology and bioinformatics:

After three decades of competitions, the assessors declared that AlphaFold 2 had succeeded in solving a challenge open for 50 years: to develop a method that can accurately, generally and competitively predict a protein structure from its sequence (or, well, a multiple sequence alignment, as we will see later). There are caveats and edge cases, as in any application — but the magnitude of the breakthrough, as well as its potential impact, are undeniable.

Comparing AlphaFold 2’s results to those of other methods: “AlphaFold 2’s accuracy is simply on a whole different level.”

Similarly, Mohammed AlQuraishi, Professor of Systems Biology at Columbia, gave praise to DeepMind’s achievements:

CASP14 #s just came out and they’re astounding—DeepMind looks to have solved protein structure prediction. Median GDT_TS went from 68.5 (CASP13) to 92.4!!!! Cf. their 2nd best CASP13 struct scored 92.8 (out of 100). Median RMSD is 2.1Å. I think it's over https://t.co/dQ1BOJWuwn

— Mohammed AlQuraishi (@MoAlQuraishi) November 30, 2020

In his detailed blog post last year on the first iteration of AlphaFold, AlphaFold @ CASP13: “What just happened?”, Professor AlQuraishi discussed what DeepMind’s progress meant for academia and pharmaceutical companies:

- This is “an indictment of academic science” - “There are dozens of academic groups, with researchers likely numbering in the (low) hundreds, working on protein structure prediction. […] For DeepMind’s group of ~10 researchers, with primarily (but certainly not exclusively) ML expertise, to so thoroughly route everyone surely demonstrates the structural inefficiency of academic science.”

- This is also “an indictment of pharma” - “What is worse than academic groups getting scooped by DeepMind? The fact that the collective powers of Novartis, Pfizer, etc, with their hundreds of thousands (~million?) of employees, let an industrial lab that is a complete outsider to the field, with virtually no prior molecular sciences experience, come in and thoroughly beat them on a problem that is, quite frankly, of far greater importance to pharmaceuticals than it is to Alphabet.”

Responding to this year’s AlphaFold 2 is his new post AlphaFold2 @ CASP14: “It feels like one’s child has left home.”:

- While AlphaFold 2 still has a lot of caveats, Professor AlQuraishi defends using “solved” to describe protein folding, at least in the scientific sense. He argues the remaining deficiencies of AlphaFold 2 are not scientific problems, but rather engineering ones. While engineering problems can still be exceedingly difficult, “competent domain experts know the pieces that need to fall into place to solve them.”

- As for AlphaFold 2’s potential applications to advance biology as a whole: “It won’t happen overnight. None of what I’m saying here will. It will take years and maybe decades, but now that protein structure prediction has become an engineering exercise, we know that many of these ideas can be realized.”

Specifically for drug development:

I will end this section with the question that gets asked most often about protein structure prediction—will it change drug discovery? Truthfully, in the short term, the answer is most likely no. But it’s complicated. One important thing to note is that, of the entire drug development pipeline, the early discovery stage is just that, an early stage. Even if crystallography were to become fast and routine, it would still not fundamentally alter the dynamics of drug discovery as it is practiced today, as most of the cost is in the later stages of drug development beyond medicinal chemistry and well into biology and physiology. Reliable protein structure prediction doesn’t change that.

However, not everyone saw the same magnitude of advancement in AlphaFold 2. In the post No, DeepMind has not solved protein folding, Stephen Curry, Professor of Structural Biology at Imperial College London, cautioned against using the word “solved” to describe protein folding:

But we are not yet at the point where we can say that protein folding is ‘solved’. For one thing, only two-thirds of DeepMind’s solutions were comparable to the experimentally determined structure of the protein. This is impressive but you have to bear in mind that they didn’t know which two-thirds of their predictions were correct until the comparison with experimental solutions was made. Would you buy a satnav that was only 67% accurate? So a dose of realism is required. It is also difficult to see right now, despite DeepMind’s impressive performance, that this will immediately transform biology.

Despite AlphaFold 2’s average accuracy of 1.6 Å:

it’s still not nearly good enough for delivering reliable insights into protein chemistry or drug design. To do that, we want to be confident of atomic positions to within a margin of around 0.3Å. AlphaFold 2’s best prediction has an RMSD for all atoms of 0.9 Å. Many of the predictions contributing to their average of 1.6 Å will have deviations in atomic positions even greater than that. So, despite the claims, we’re not yet ready to use Alphafold 2 to create new drugs. There are other reasons not to believe that the protein folding problem is ‘solved’. AI methods rely on learning the rules of protein folding from existing protein structures. This means that it may find it more difficult to predict the structures of proteins with folds that are not well represented in the database of solved structures.

Max Little, Professor of Computer Science at the University of Birmingham, also comments on the potential challenges the AlphaFold 2 might run into with novel proteins outside of CAPS:

We can’t really be sure how well AlphaFold will work when faced with the far more rich and varied array of proteins found in the real world of living organisms

The Biologist magazine gave similar remarks:

Structural biologists are excited about this clear step forward in protein-structure prediction, but have urged caution against hyperbole. Firstly, there are some blind spots in AlphaFold’s ability to visualise proteins in 3D: because its algorithms feed from the world’s databases of solved structures, it will not be able to predict proteins with folds that are not well represented in these data stores. Also, the CASP tests did not include predictions of notoriously tricky “multi-protein” complexes and larger cellular structures like ribosomes. As these are some of the most interesting structures in biology, those who specialise in existing techniques to understand them experimentally are not likely to be out of a job any time soon.

Other researchers concurred that while AlphaFold 2’s results are impressive, protein folding is yet to be solved. Lior Pachter, Professor of Computational Biology at CalTech, tweets:

A friend (who does not work in science) asked me today whether it is true that "protein folding has been solved". My short answer:

— Lior Pachter (@lpachter) December 1, 2020

The AlphaFold method produced very impressive results on CASP14. Protein folding is not a solved problem. pic.twitter.com/ZMc4grC5iP

Mike Thompson, Professor of Structural Biology at UC Merced, echoes a similar sentiment while emphasizing that DeepMind should share its code:

It's laughable to declare protein structure prediction a "solved" problem. The reported precision in the best predicted models is still 10-20 times worse than coordinate precision in typical experimental structures. https://t.co/k2zLly1Bew

— Mike Thompson (@mctucsf) November 30, 2020

Frankly, the hype serves no one. DeepMind can now never live up to the promise that's been made and have dragged experimentalists through the mud in the process. Also, until DeepMind shares their code, nobody in the field cares and it's just them patting themselves on the back

— Mike Thompson (@mctucsf) December 1, 2020

On the industry side, Vishal Gulati, a healthcare startup investor, shared similar views in the post A Breakthrough in Protein Folding Unfolds:

Despite this being the biggest thing that has happened in protein folding, the protein folding problem is not yet solved. Compared to the problem of protein folding, CASP is a game. It is a very hard game but it is a reduced problem set which helps us train our tools and standardise performance. It is a necessary step but it is not sufficient.

James Wang, Analyst at ARK Invest, highlights the potential accessibility of AlphaFold and AlphaFold-like algorithms:

🚀 State of neural networks 2020 🚀

— James Wang (@jwangARK) December 2, 2020

AlphaFold shows it's possible to achieve ground-breaking results using public datasets and modest compute costs. pic.twitter.com/jQNtZEIKEf

For real-world applications, many noted that predicting protein structure is only one step of drug discovery. Significantly accelerating drug discovery seems unlikely, with one biotech exec, Michael Gilman, CEO of Arrakis Therapeutics, making his thoughts clear:

Bullsh*t.

— Michael Gilman (@michael_gilman) December 1, 2020

From the Source

Both Demis Hassabis, CEO of DeepMind and Sundar Pichai, CEO of Alphabet, DeepMind’s parent company, described AlphaFold 2 as “breakthroughs”:

Thrilled to announce our first major breakthrough in applying AI to a grand challenge in science. #AlphaFold has been validated as a solution to the ‘protein folding problem’ & we hope it will have a big impact on disease understanding and drug discovery: https://t.co/P53t2TxVRa

— Demis Hassabis (@demishassabis) November 30, 2020

.@DeepMind's incredible AI-powered protein folding breakthrough will help us better understand one of life’s fundamental building blocks + enable researchers to tackle new and hard problems, from fighting diseases to environmental sustainability. https://t.co/kpr8EAx34h

— Sundar Pichai (@sundarpichai) November 30, 2020

DeepMind also released a mini documentary, portraying the advancement as a surprising breakthrough:

In response to the ensuing criticism mentioned above, John Moult, Chair of CASP, remains optimistic. With regard to code-sharing: “Although code-sharing is obviously desirable, and some groups do it, it has never been the norm. Not clear why DeepMind should be held to a higher standard than others.”

Fifty years of listening to false claims about this problem has made me the world’s biggest skeptic. But I have looked at these results very carefully … Clearly, this is just the beginning of what DeepMind and others will achieve with these sorts of approaches.

Our Perspective

While Alphafold’s progress in this area is very encouraging and points to an exciting future, even the most bullish publications understand that the software won’t immediately replace existing tools such as X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy. Immediate impacts on more practical matters, i.e. drug development, won’t be immediately forthcoming. The average drug takes an average of 10 years to make it to the marketplace from initial discovery, with the bulk of that period spent in clinical trials. In other words, even if AlphaFold 2 significantly accelerates drug discovery — it doesn’t — there will still be serious bottlenecks in the overall drug development process.

If forced to make a comparison with another technological inflection point, Alphafold 2’s results could be likened to the release of the iPhone in 2007. It’s new, different, and signals that the playing field has changed. It offers the ability for researchers to spend their time on edge problems or the areas of protein folding that Alphafold 2 (or its successor) cannot handle.

It’s hard to fault the scientists for being excited when they can finally see the light at the end of the protein-folding tunnel, but the average individual probably won’t see any immediate and material impacts that stem directly from this advancement. Rather, Alphafold 2’s success should be framed in the context of all progress in the life sciences—as one important step in the very long journey to understand ourselves.