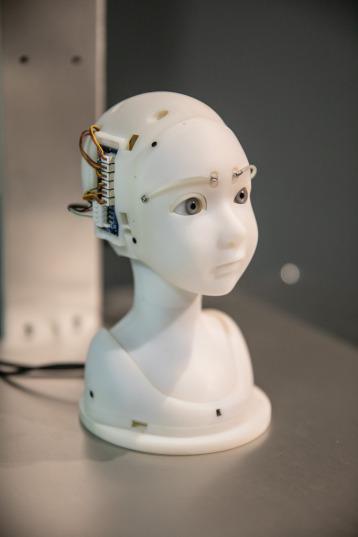

Symbiotic human-level AI: fear not, for I am your creation

Human-level AI may well be possible — and we may not have to fear it

Image credit: Techcrunch

Olaf Witkowski is an EON Research Scientist at the Earth-Life Science Institute in Tokyo, and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. He is also a Founding Member of YHouse — a nonprofit transdisciplinary research institute focused on the study of awareness, artificial intelligence and complex systems. He received his PhD under Takashi Ikegami, from the Computer Science Department of the University of Tokyo. This essay was originally posted on his site on October 19th, 2018.

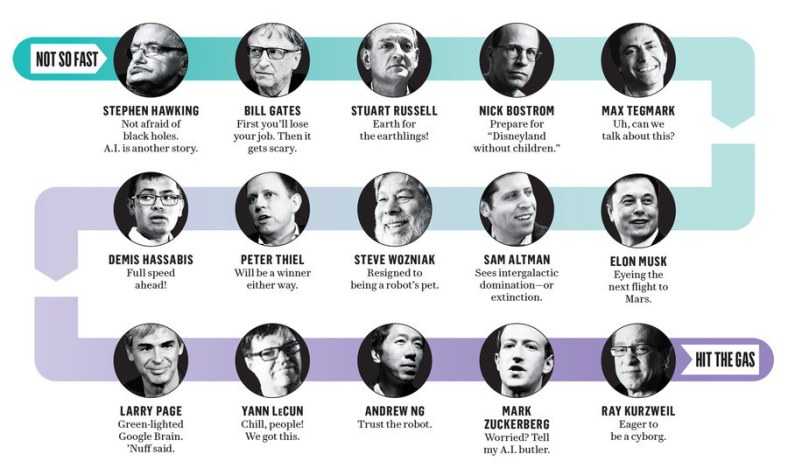

This opinion piece was prompted by the recent publication of Stephen Hawking’s last writings, where he mentioned some ideas on superintelligence. Although I have the most utter respect for his work and vision, I am afraid some of it may be read in a very misleading way.

At the same time, there is just a number of myths concerning “AI anxiety” I believe are easy to debunk. This is what I’ll try to do here. So off we go, let’s talk about AI, transhumanism, the evolution of intelligence, and self-reflective AI.

Myth 1: AI to inevitably supercede humans

Superintelligence, humans’ last invention

The late physicist Stephen Hawking was really wary of the dangers of AI. His last writings were published in the UK’s Sunday Times, where he raises the well-known problem of alignment. The issue is about regulating AI, since in the future, once AI develops a will of its own, its will might conflict with ours. The following quote is very representative of this type of idea:

“In short, the advent of super-intelligent AI would be either the best or the worst thing ever to happen to humanity. The real risk with AI isn’t malice, but competence. A super-intelligent AI will be extremely good at accomplishing its goals, and if those goals aren’t aligned with ours we’re in trouble. You’re probably not an evil ant-hater who steps on ants out of malice, but if you’re in charge of a hydroelectric green-energy project and there’s an anthill in the region to be flooded, too bad for the ants. Let’s not place humanity in the position of those ants. – Stephen Hawking

As Turing’s colleague Irving Good pointed out in 1965, once intelligent machines are able to design even more intelligent ones, the process could be repeated over and over: “Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control”. Vernor Vinge, an emeritus professor of computer science at San Diego State University and a science fiction author, said in his 1993 essay “The Coming Technological Singularity” that this very phenomenon could mean the end of the human era, as the new superintelligence advance technologically at an incomprehensible rate and potentially outdo any human feat. At this point, we caught the essence of what is scary to the reader, and it is exactly what feeds the fear on this topic, including for deep thinkers such as Stephen Hawking.

Hawking is only one among many whistleblowers, from Elon Musk to Stuart Russel, including AI experts too. Elizier Yudkowsky, in particular, remarked that AI doesn’t have to take over the whole world with robot or drones or any guns or even the Internet. He says:

“It’s simply dangerous because it’s smarter than us. Suppose it can solve the science technology of predicting protein structure from DNA information. Then it just needs to send out a few e-mails to the labs that synthesize customized proteins. Soon it has its own molecular machinery, building even more sophisticated molecular machines.”

Essentially, the danger of AI goes beyond the specificities of its possible embodiments, straight to the properties attached to its superior intelligent capacity. Hawking says he fears the consequences of creating something that can match or surpass humans. Humans, he adds, who are limited by slow biological evolution, couldn’t compete and would be superseded. In the future AI could develop a will of its own, a will that is in conflict with ours.

Although I understand the importance of being as careful as possible, I tend to disagree with this claim. In particular, there is no reason human evolution has to be slower. Not only can we engineer our own genes, but we can also augment ourselves in many other ways. Now, I want to make it clear that I’m not advocating for any usage of such technologies without due reflection on societal and ethical consequences. I want to point out that such doors will be open to our society, and are likely to become usable in the future.

Augmented humans

Let’s talk more about ways of augmenting humans. This goes through defining carefully what technological tools are: any piece of machinery that augments a system’s capacity in its potential action space. Tools such as hammers and nails fall under this category. So do the inventions of democracy and agriculture, respectively a couple of thousand and around 10,000 years ago. If we go further back, more than 100 million years ago, animals invented eusocial societies. Even earlier, around 2 billion years ago, single cells surrounded by membranes incorporated other membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria, and sometimes chloroplasts too, forming the first eukaryotic cells. In fact, each transition in evolution corresponds to the discovery of some sort of technology too. All these technologies are to be understood in the acception of augmentation of the organism’s capacity.

Humans can be augmented not only by inventing tools that change their physical body, but also their whole extended embodiment, including the clothes they wear, the devices they use, and even the cultural knowledge they hold, for all pieces are constituents of who they are and how they affect their future and the future of their environment. It’s not a given that any of the extended human’s parts will be slower to evolve slower than AI, which is most evident for the cultural part. It’s not clear either that they will evolve faster, but we realize how one must not rush to conclusions.

Myth 2: advanced AI cannot coexist peacefully with humans

On symbiotic relationships

Let’s come back a moment on the eukaryotic cell, one among many of nature’s great inventions. Eukaryotes are organisms which, as opposed to simple bacteria or archea before them, possess a nucleus enclosed within membranes. They may also contain mitochondria (energy storage organelles, which generate ATP for the cell), and sometimes chloroplasts (organelles capable of performing photosynthesis, converting photons from sunlight into stored energy molecules). An important point about eukaryotes, is they did not kill mitochondria, or vice-versa. Nor did some of them enslave chloroplasts. In fact, there is no such clear cut in nature. A better term is symbiosis. In the study of biological organisms, symbioses qualify interactions between different organisms sharing the physical medium in which they live, often (though not necessarily) to the advantage of both. It may be important to note that symbiosis, in the biological sense, does not imply a mutualistic, i.e. win-win, situation. I here use symbiosis as any interaction, beneficial or not for each party.

Symbiosis seems very suitable to delineate the phenomenon by which an entity such as a human invents a tool by incorporating in some way elements of its environment, or simply ideas that are materialized into a scientific innovation. If that’s the case, it is natural to consider AI and humans as just pieces able to interact with each other.

There are several types of symbiosis. Mutualism, such as a clownfish living in a sea anemone, allows two partners to benefit from the relationship. In commensalism, only one species benefits while the other is neither helped nor harmed. An example of that is remora fish which attach themselves to whales, sharks, or rays and eat the scraps their hosts leave behind. The remora fish gets a meal, while their host arguably gets nothing. The last big one is parasitism, where an organism gains, while another loses. For example, the deer tick (which happens to be very present here in Princeton) is a parasite that attaches to the warmblooded animal, and feeds on its blood, adding up risks of Lyme disease to the loss of blood and nutrients.

Once technology, AI, becomes autonomous, it’s easy to imagine that all three scenarios could happen. It’s natural to envisage the worst case scenario: the AI could become the parasite, and the human could lose in fitness, eventually dying off. Now, this is important to weigh against other scenarios, taking into account the respective probabilities for each one to happen.

The point is that inventions of tools result in symbiotic relationships, and in such relationships, the parts become tricky to distinguish from each other. This is not without reminding us of the extended mind problem, approached by Andy Clark (Clark & Chalmers 1998). The idea, somewhat rephrased, is that it’s hard for anyone to locate boundaries between intelligent beings. If we consider just the boundaries of our skin, and say that outside the body is outside the intelligent entity, what are tools such as notebooks, without which we wouldn’t be able to act the same way? Clark and Chalmers proposed an approach called active externalism, or extended cognition, based on the environment driving cognitive processes. Such theories are to be taken with a grain of salt, but surely apply nicely to the way we can think of such symbioses and their significance.

Integrated tools

Our tools are part of ourselves. When we use a tool, such as a blind person’s cane or an “enactive torch” (Froese et al. 2012), it’s hard to tell where the body boundary ends, and where the tool begins. In fact, the reports we make using those tools are often that the limit of the body moves to the edge of the tool, instead of remaining contained within the skin.

Now, one could say that AI is a very complex object, which can’t be considered as a mere tool like the aforementioned cases. This is why it’s helpful to thought-experimentally replace the tool by a human. An example would be psychological manipulation, through some abusive or deceptive tactics, such as a psychopathic businessman bullying his insecure colleague into extra work for him, or a clever young boy grooming his mother into buying him what he wants. Since the object of the manipulation is an autonomous, goal-driven human, one can now ask them how they feel as well.

And in fact, it has been reported by psychology specialists like George Simon (Simon & Foley 2011) that people being manipulated do feel a perceived loss of their sense of agency, and struggle in finding the reasons why they acted in certain ways. In most cases, they will invent fictitious causes, which they will swear are real. Other categories of examples could be as broad as social obligations, split-brain patients or any external mechanisms that force people (or living entities for that matter, as these examples are innumerable in biology) to act in a certain way, without them having a good reason of their own for it.

As small remark, I heard some people tell me the machine could be more than a human, in some way, breaking the argument before. Is it really? To me, once it is autonomously goal-driven, the machine comes close enough to a human being for the purpose of comparing the human-machine interaction to the human-human one. Surely, one may be endowed with a better prediction ability in certain given situations, but I don’t believe anything is conceptually different.

Myth 3: advanced AI needs to be controlled

Delusions of control

Humans seem to have the tendency to feel in control even when not. This persists even where AI is already in control. If we take the example of Uber, where an algorithm is responsible for assigning drivers to their next mission. Years earlier, Amazon, YouTube and many other platforms were already recommending their users what to watch, listen to, buy, or do next. In the future, these types of recommendation algorithms are likely to only expand their application domain, as it becomes more and more efficient and useful for an increasing number of domains to incorporate the machine’s input in decision-making and management. One last important example is the automatic medical advice which machine learning is currently becoming very efficient at. Based on increasing amounts of medical data, it is easier and safer in many cases to at least base a medical calls, from identification of lesions to decisions to perform surgery, on the machine’s input. We reached the point where it clearly would not be ethical to ignore it.

However, the impression of free will is not an illusion: in most examples of recommendation algorithms, we still can make the call. It becomes similar to choices of cooperation in nature. They are the result of a free choice (or rather, their evolutionary closely related analog), as the agent may choose not to couple its behavior to the other agent.

Dobby is free

The next question is naturally: what does the tool becomes, once detached from the control of a human? Well, what happens to the victim of a manipulative act, once released from the control of their manipulator? Effectively, they just come back in control again. Whether they perceive it or not, their autonomy is regained, making their action caused again (more) by their own internal states (than when under control).

AI, once given the freedom to act on its own, will do just that. If it has become a high form of intelligence, it will be free to act as such. The fear is here well justified: if the machine is free, it may be dangerous. Again, the mental exercise of replacing the AI with a human is helpful.

Homo homini lupus. Humans are wolves to each other. How many situations can we find in our daily lives in which we witnessed someone choose a selfish act instead of the nice, selfless option? When I walk on the street, take the train, go to a soccer match, how do I even know that all those humans around me won’t hurt me, or worse? Even nowadays, crime and war plague our biosphere. Dangerous fast cars, dangerous manipulations of human pushed to despair, anger, fear, suffering surround us wherever we go, if we look closely enough. Why are we not afraid? Habituation is certainly one explanation, but the other is that society shields us. I believe the answer lies in Frans de Waal’s response to “homo homini lupus”. The primatologist how the proverb, beyond failing to do justice to canids (among the most gregarious and cooperative animals on the planet (Schleidt and Shalter 2003)), denies the inherently social nature of our own species.

The answer seems to lie indeed in the social nature of human-to-human relations. The power of society, which uses a great number of concomitant regulatory systems, each composed of multiple layers of cooperative mechanisms, is exactly what keeps each individual’s selfish behavior in check. This is not to say anything close to the “veneer theory” of altruism, which claims that life is fundamentally selfish with an icing of pretending to care on top. On the contrary, rich altruistic systems are fundamental, and central in the sensorimotor loop of each and every individual in groups. Numerous simulations of such altruism have been reproduced in silico, that show a large variety of mechanisms for their evolution (Witkowski & Ikegami 2015).

Dobby is this magical character from J. K. Rowling’s series of novels, who is the servant (or rather the slave) of some wizard. His people, if offered a piece of clothing from his masters, are magically set free. So what happens once “Dobby is free”, which in our case, corresponds to some AI, somewhere, beings made autonomous? Again, the case is no different from symbiotic relationships in the rest of nature. Offered degrees of freedom independent from human control, AIs get to simply share humans’ medium: the biosphere. They are left interacting together to extract free energy from it while preserving it, and preparing for the future of their destinies combined.

Autonomous AI = hungry AI

Not everyone thinks machines will be autonomous. In fact, Yann Lecun expressed, as reported by BBC, that there was “no reason why machines would have any self-preservation instinct”. At the AI conference I attended, organized by David Chalmers at NYU, in 2017, Lecun also mentioned that we would be able to control AI with appropriate goal functions.

I understand where Lecun is coming from. AI intelligence is not like human intelligence. Machines don’t need to be built with human drives, such as hunger, fear,lust and thirst for power. However, believing AI can be kept self-preservation-free is fundamentally misguided. One simple reason has been pointed out by Stuart Russel, who explains how drives can emerge from simple computer programs. If you program a robot to bring you coffee, it can’t bring you coffee if it’s dead. As I’d put it, as soon as you code an objective function into an AI, you potentially create subgoals in it, which can be comparable to human emotions or drives. Those drives can be encoded in many ways, included in the most implicit way. In artificial life experiments, from software to wetware, the emergence of mechanisms akin to self-preservation in emerging patterns is very frequent, and any students fooling around with simulations for some time can realize that early on.

So objective functions drive to drives. Because every machine possesses some form of objective function, even implicitly, it will make for a reason to preserve its own existence to achieve that goal. And the objective function can be as simple as self-preservation, some function that appeared early on in the first autonomous systems, i.e. the first forms of life on Earth. Is there really a way around it? I think it’s worth thinking about, but I doubt it’s the case.

How to control an autonomous AI

If any machine has drives, then how to control it? Most popular thinkers, specializing in the existential problem and dangers of future AI, seem to be interested in alignment of purposes, between humans and machines. I see how the reasoning goes: if we want similar things, we’ll all be friends in the best of worlds. Really, I don’t believe that is sufficient or necessary.

The solution that usually comes up is something along the off switch. We build all machines with an off switch, and if the goal function is not aligned with human goals, we switch the device off. The evident issue is to make sure that the machine, in the course of self-improving its intelligence, doesn’t eliminate the off switch or make it inaccessible.

What other options are we left with? If the machine’s drives are not aligned with its being controlled by humans, then the next best thing is to convince it to change. We are back on the border between agreement and manipulation, both based on our discussion above about symbiotic relationships.

Communication, not control

It is difficult to assess the amount of cooperation in symbioses. One way to do so is to observe communication patterns, as they are key to the integration of a system, and, arguably, its capacity to compute, learn and innovate. I touched upon this topic before in this blog.

The idea is that anyone with an Internet connection already has access to all the information needed to conduct research, so in theory, scientists could do their work alone locked up in their office. Yet, there seems to be a huge intrinsic value to exchanging ideas with peers. Through repeated transfers from mind to mind, concepts seem to converge towards new theorems, philosophical concepts, and scientific theories.

Recent progress in deep learning, combined with social learning simulations, offers us new tools to model these transfers from the bottom up. However, in order to do so, communication research needs to focus on communication within systems. The best communication systems not only serve as good information maps onto useful concepts (knowledge in mathematics, physics, etc.) but they are also shaped so as to be able to naturally evolve into even better maps in the future. With the appropriate communication system, any entity or group of entities has the potential to completely outdo another one.

A project I am working on in my daytime research, is to develop models of evolvable communication between AI agents. By simulating a communication-based community of agents learning with deep architectures, we can examine the dynamics of evolvability in communication codes. This type of system may have important implications for the design of communication-based AI capable of generalizing representations through social learning. This also has the potential to yield new theories on the evolution of language, insights for the planning of future communication technology, a novel characterization of evolvable information transfers in the origin of life, and new insights for communication with extraterrestrial intelligence. But most importantly, the ability to gain explicit insight about its own states, and being able to internally communicate about them, should allow an AI to teach itself to be wiser through self-reflection.

Myth 4: advanced AI is a zero sum game

Shortcomings of human judgment about AI

Globally, it’s hard to emit a clear judgment on normative values in systems. Several branches of philosophy spent a lot of effort in that domain, without any impressive insights. It’s hard to dismiss the idea that humans might be stuck in their biases and errors, rendering it impossible to make an informed decision on what constitutes a “bad” or “good” decision in the design of a superintelligence.

Also, it’s very easy to draw on people’s fears. I’m afraid that this might be driving most of the research, in the near future. We saw how easy it was to fund several costly institutes to think about “existential risks”. Of course, it is only naturally sane for biological systems to act this way. The human mind is famously bad at statistics, which, among other weaknesses, makes it particularly risk averse. And indeed, on the smaller scale, it’s often better to be safe than sorry, but at the scale of technological advance, being safe may mean stagnate for a long time. I don’t believe we have so much time to waste. Fortunately, there are people thinking that way too, who make the science progress. Whether they act for the right reasons or not would be a different discussion.

Now, I’m actually glad the community that is thinking deeply about these questions is blooming lately. As long as they can hold off a bit on the whistleblowing and crazy writing, and focus on the research, and pondered reflection, I’ll be happy. What would make it better is the capacity to integrate knowledge from different fields of sciences, by creating common languages, but that’s also for another post.

Win-win, really

The game doesn’t have to be zero or negative sum. A positive-sum game, in game theory, refers to interactions between agents in which the total of gains and losses is greater than zero. A positive sum typically happens when the benefits of an interaction somehow increase for everyone, for example when two parties both gain financially by participating in a contest, no matter who wins or loses.

In nature, there are plenty of such positive sum games, especially in higher cognitive species. It was even proposed that evolutionary dynamics favoring positive-sum games drove the major evolutionary transitions, such as the emergence of genes, chromosomes, bacteria, eukaryotes, multicellular organisms, eusociality and even language (Szathmáry & Maynard Smith 1995). For each transition, biological agents entered into larger wholes in which they specialized, exchanged benefits, and developed safeguard systems to prevent freeloading to kill off the assemblies.

In the boardgame “Settlers of Catan”, individual trades are positive-sum for the two players involved, but the game as a whole is zero-sum, since only one player can win. This a simple example of multiple levels of games happening simultaneously.

Naturally, this happens at the scale of human life too, where a common example is the trading of surpluses, as when herders and farmers exchange wool and milk for grain and fruit, is a quintessential example, as is the trading of favors, as when people take turns baby-sitting each others’ children.

Earlier, we have mentioned the metaphor of ants, which get trampled on while the humans accomplish tasks that they would deem far too important to care about the insignificant loss of a few ants’ lives.

What is missing in the picture? The ants don’t reason at a level anywhere close to the way we do. As a respectful form of intelligence, I’d love to communicate my reasons to ants, but I feel like it would be a pure waste of time. One generally supposes this would this still be the case if we transpose to the relationship between humans and AI. Any AI supposedly wouldn’t waste their time showing respect to human lives, so that if higher goals were to be at stake, it would sacrifice humans in a heartbeat. Or would they?

I’d argue there are at least two significant differences between these two situations. I concede that the following considerations are rather optimistic, as they presuppose a number of assumptions: the AI must share a communication system with humans, must value some kind of wisdom in its reasoning, and maintain high cooperative levels.

The first reason is that humans are reasoning creatures. The second is that humans live in close symbiosis with AI, which is far from being the case between ants and humans. About the first point, reasoning constitutes an important threshold of intelligence. Before that, you can’t produce complex knowledge of logic, inference. You can’t construct complicated knowledge of mathematics, or scientific method.

As for the second reason, close symbiotic relation, it seems important to notice that AI came as an invention from humans, a tool that they use. Even if the AI becomes autonomous, it is unlikely that it would remove itself right away from human control. In fact, it is likely, just like many forms of life before it, that it will leave a trace of partially mutated forms on the way. Those forms will be only partially autonomous, and constitute a discrete but dense spectrum along which autonomy will rise. Even after the emergence of the first autonomous AI, each of the past forms is likely to survive and still be used as a tool by humans in the future. This track record may act as a buffer, which will ensure that the any superintelligent AI can still communicate, and cooperate.

Two entities that are tightly connected won’t break their links easily. Think of a long-time friend. Say one of you becomes suddenly much more capable, or richer than the other. Would you all of a sudden start ignoring, abusing or torturing your friend? If that’s not your intention, the AI is no different.

Hopeful future, outside the Solar System

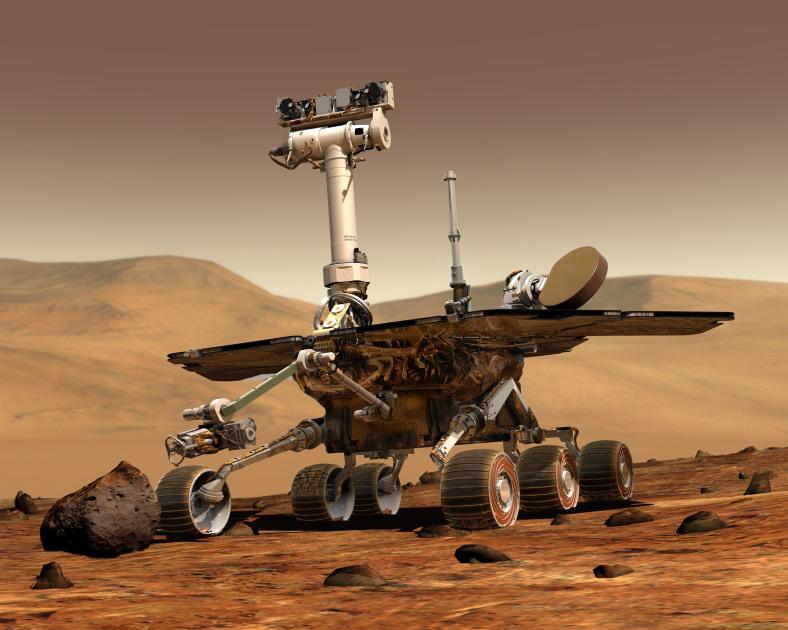

I’d like to end this piece on ideas from Hawking’s writings with which I wholeheartedly agree. We definitely need to take care of our Earth, the cradle of human life. We should also definitely explore the stars, not to leave all our eggs in only one basket. To accomplish both, we should use all technologies available, which I’d classify in two categories: human-improvement, and design of replacements for humans. The former, by using gene editing and sciences that will lead to the creation of superhumans, may allow us to survive interstellar travel. But the latter, helped by energy engineering, nanorobotics and machine learning, will certainly allow us to do it much earlier, by designing ad-hoc self-replicating machines capable of landing on suitable planets and mining material to produce more colonizing machines, to be sent on to yet more stars.

These technologies are something my research field, Artificial Life, has been contributing to for more than three decades. By designing what seems mere toy models, or pseudo-forms of life in wetware, hardware and software, the hope is to soon enough understand the fundamental principles of life, to design life that will propel itself towards the stars and explore more of our universe.

Why is it crucial to leave Earth? One important cause, beyond mere human curiosity, is to survive possible meteorite impacts on our planet. Piet Hut, the director of the interdisciplinary program I am in at the moment, at the Institute for Advanced Study, published a seminal paper explaining how mass extinctions can be caused by cometary impacts (Hut et al. 1987). The collision of a rather smaller bodies with the Earth, about 66 million years ago, is thought to have been responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs, along with any large form of life.

Such collisions are rare, but not so rare that we should not be worried.Asteroids with a 1 km diameter strike Earth every 500,000 years on average, while 5 km bodies hit out planet approximately once every 20 million years (Bostrom 2002, Marcus 2010). Again, quoting Hawking, if this is all correct, it could mean intelligent life on Earth has developed only because of the lucky chance that there have been no large collisions in the past 66 million years. Other planets may not have had a long enough collision-free period to evolve intelligent beings.

If abiogenesis, the emergence of life on Earth, wasn’t so hard to produce, the gift of the right conditions for long enough periods of time on our planet was probably essential. Not only good conditions for a long time, but also the right pace of change of these conditions through time too, to get mechanisms to learn to memorize such patterns, as they impact on free energy foraging (Witkowski 2015, Ofria 2016). After all, our Earth is around 4.6 billion years old, and it took only a few hundred millions years at most for life to appear on its surface, in relatively high variety. But much longer was necessary for complex intelligence to evolve, 2 billion years for rich, multicellular forms of life, and 2 more billion years to get to the Anthropocene and the advent of human technology.

To me, the evolution of intelligence and the fundamental laws of its machinery is the most fascinating question to explore as a scientist. The simple fact that we are able to make sense of our own existence is remarkable. And surely, our capacity to deliberately design the next step in our own evolution, that will transcend our own intelligence, is literally mind-blowing.

There may be many ways to achieve this next step. It starts with humility in our design of AI, but the effort we will invest in our interaction with it, and the amount of reflection we will dedicate to the integration with each other are definitely essential to our future as lifeforms, in this corner of the universe.

I’ll end on Hawking’s quote: “Our future is a race between the growing power of our technology and the wisdom with which we use it. Let’s make sure that wisdom wins”.

References

(by order of appearance)

Hawking, S. (2018). Last letters on the future of life on planet Earth. The Sunday Times, October 14, 2018.

Eörs Szathmáry and John Maynard Smith. The major evolutionary transitions. Nature, 374(6519):227–232, 1995.

Clark, A. (2015). 2011: What Scientific Concept Would Improve Everybody’s Cognitive Toolkit?.

Froese, T., McGann, M., Bigge, W., Spiers, A., & Seth, A. K. (2012). The enactive torch: a new tool for the science of perception. IEEE Transactions on Haptics, 5(4), 365-375.

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. analysis, 58(1), 7-19.

Simon, G. K., & Foley, K. (2011). In sheep’s clothing: Understanding and dealing with manipulative people. Tantor Media, Incorporated.

Hut, P., Alvarez, W., Elder, W. P., Hansen, T., Kauffman, E. G., Keller, G., … & Weissman, P. R. (1987). Comet showers as a cause of mass extinctions. Nature, 329(6135), 118.

Bostrom, N. (2002). “Existential Risks: Analyzing Human Extinction Scenarios and Related Hazards”, Journal of Evolution and Technology, 9.

Marcus, R., Melosh, H. J., Collins, G. (2010). “Earth Impact Effects Program”. Imperial College London / Purdue University. Retrieved 2013-02-04.

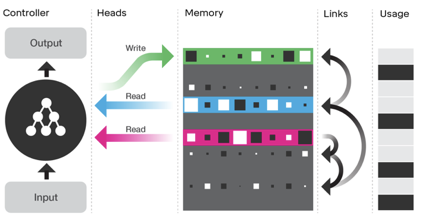

Graves, A., Wayne, G., Reynolds, M., Harley, T., Danihelka, I., Grabska-Barwińska, A., … & Badia, A. P. (2016). Hybrid computing using a neural network with dynamic external memory. Nature, 538(7626), 471.

Witkowski, Olaf (2015). Evolution of Coordination and Communication in Groups of Embodied Agents. Doctoral dissertation, University of Tokyo.

Ofria, C., Wiser, M. J., & Canino-Koning, R. (2016). The evolution of evolvability: Changing environments promote rapid adaptation in digital organisms. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Artificial Life 13 (pp. 268-275).