Police Misuse of Facial Recognition - Three Wrongful Arrests and Counting

An overview of how multiple individuals have already been harmed by facial recognition algorithms, with more likely to follow.

Image credit: Mahesh Paolini-Subramanya via Medium

Summary

In the wake of massive leaps in performance, facial recognition systems are being adopted more and more in the US,particularly by police departments. However, facial recognition systems are known to be biased and flawed, and several documented incidents in which people--all of whom are African American--have been wrongly targeted by the police due to facial recognition have already happened. Given these incidents and the known limitations of facial recognition systems, we should think carefully about how to mitigate the negative effects of these systems’ inevitable mistakes.

Background

Facial recognition, or the task of matching images of faces to the identity of the person in the picture, is one of the oldest problems studied in Computer Vision and AI more broadly. As the name might suggest, facial recognition is a way to identify a person using their face. The study of this problem began in the 1960s when Woody Bledsoe developed measurements that would help classify photos of human faces, though this was dependent on human annotation and so not fully algorithm-based (NYT).

.](/assets/img/briefs/wrongful-arrests/bledsoe.png)

As facial recognition systems improved in the proceeding decades, it was only a matter of time they would be deployed outside the research lab for law enforcement purposes. An early instance of this occurred when Tampa, Florida used a facial recognition surveillance system as it hosted Super Bowl XXXV in 2001 (NYT). An ABC piece on the Super Bowl incident states that as “fans stepped through the turnstiles at Super BowlXXXV, a camera snapped their image and matched it against a computerized police lineup of known criminals.” and that it “highlighted a debate about the balance between individual privacy and public safety.”

.](/assets/img/briefs/wrongful-arrests/history.png)

Since that incident, the technologies underlying facial recognition have improved substantially. The “ImageNet moment” and rise of deep learning enabled immensely more powerful algorithms that could be used for visual tasks like facial recognition. However, the performance of these algorithms is tied closely with the amount and kinds of data they are fed--if they see more faces, they can better figure out what aspects of faces are useful for identifying people. Companies like Facebook have `created massive datasets of user photos--without those users’ knowledge--to train powerful computer vision algorithms. Jessamyn West, a librarian in rural Vermont, was understandably unhappy when she found a photo she uploaded to Flickr had been used in a facial recognition dataset: “I think if anybody had asked at all, I would have had a different feeling.” When these datasets are not collected carefully, they can also cause bias in the algorithms they are used to train (in the sense that these algorithms unintentionally perform worse for some demographic groups) because they might over-represent a particular demographic group. As a result, the benefits of these performance improvements didn’t accrue equally to everyone.

.](/assets/img/briefs/wrongful-arrests/collage.png)

A year after the 2014 Snowden revelations again brought facial recognition and data privacy to the fore, Google’s Photos app came under fire for a sign of racial bias in its algorithm: it sometimes labeled black people as “gorillas” (Google’s unimaginative solution was to block the image categories “gorilla,” “chimp,” “chimpanzee,” and “monkey.”). While the Photos incident concerns an image classification algorithm and not facial recognition, this incident helped reveal that machine learning algorithms are only as good as the data used to train them.

.](/assets/img/briefs/wrongful-arrests/google-photos.png)

People Harmed by Facial Recognition

Unfortunately, a few mishaps in the Photos app wouldn’t be the worst outcome of biased training data. Facial recognition systems are now used not only to tag faces in apps, but also to identify criminal suspects. Clearview AI, likely one of the most controversial companies in recent memory, developed a powerful facial recognition system to be used by law enforcement. The company drew ire and legal complaints for developing its system by scraping over three billion images from Facebook, YouTube, Venmo, and millions of other sites. You, the reader of this article, are more likely than not in Clearview’s database. Even if you have been in the background of someone else’s photo, that photo might show up in a search for you on their app. And, as Buzzfeed News reported earlier this year, “more than 7,000 individuals from nearly 2,000 public agencies nationwide have used Clearview AI to search through millions of Americans’ faces.”

While Clearview’s CEO Hoan Ton-That claims that facial recognition-enabled apps allow police officers to perform their jobs far more effectively, a *New York Times *article notes that federal and state law enforcement operators knew little about how Clearview works or who was behind it. The defects in facial recognition systems like Clearview’s have already caused a number of known harms.

The Detroit Free Press learned that in 2019, 25-year-old Michael Oliver was wrongly accused of a felony in a police investigation that used facial recognition. Oliver was arrested and charged with a felony count of larceny for supposedly reaching into a teacher’s vehicle, grabbing a cellphone from his hands, and breaking it. A facial recognition system identified Oliver as the culprit, and the police included him in a photo lineup that was shown to the teacher, who identified Oliver as the person responsible. A brief look at photos of Oliver and the culprit reveal a clear difference:

"Oliver—who has an oval-shaped face and a tattoo above his left eyebrow—only vaguely resembles the actual suspect, who has no visible tattoos, a rounder face and darker skin, according to photo evidence.

.](/assets/img/briefs/wrongful-arrests/detroit.jpg)

Fortunately, there was evidence to support Oliver’s claim that he was not involved in the incident. His court case was dismissed immediately once his lawyer presented his concerns and photos to the Wayne County Assistant Prosecutor--but his case also demonstrates that innocent citizens can be drawn into criminal cases if an algorithm determines they look like someone else. Oliver told Motherboard:

It was wrong. I lost my job and my car; my whole life had to be put on hold… That technology shouldn’t be used by police.

Oliver was not the only victim of the inaccuracy of facial recognition systems on non-white demographics. In June 2020, the New York Times reportedon another case in which Robert Williams, an African American man, was arrested by the Detroit police because a facial recognition algorithm misidentified him as a shoplifter from a video. The police officers in the case used the result of the algorithm as their main justification for the arrest, despite the report stating that “This document is not a positive identification, … it is an investigative lead only and is not probable cause for arrest.” Despite the case being dismissed two weeks later, the arrest caused Mr. Williams and his family understandable distress:

when he pulled into his driveway in a quiet subdivision in Farmington Hills, Mich., a police car pulled up behind, blocking him in. Two officers got out and handcuffed Mr. Williams on his front lawn, in front of his wife and two young daughters, who were distraught. The police drove Mr. Williams to a detention center. He had his mug shot, fingerprints and DNA taken, and was held overnight. … 30 hours after being arrested, [he was] released on a $1,000 personal bond. He waited outside in the rain for 30 minutes until his wife could pick him up. When he got home at 10 p.m., his five-year-old daughter was still awake. She said she was waiting for him because he had said, while being arrested, that he’d be right back.

.](/assets/img/briefs/wrongful-arrests/williams.png)

At the end of 2020, Nijeer Parks became the third known Black man to be affected by a bad facial recognition match. After a shoplifter was confronted by police, he gave them a fake driver’s license and escaped the scene. The photo in that license was sent to state agencies, and Nijeer Parks was found to be a facial recognition match with the photo. After a detective compared Parks’s state ID with the driver’s license and agreed it was the same person, and a Hertz employee confirmed the license photo was of the shoplifter, a warrant for Parks’s arrest was issued. As the New York Times reported, Parks spent 10 days in jail and paid about $5000 to defend himself. Several months later, his case was dismissed for lack of evidence. As in Mr. Williams’ case, that does not mean no harm was caused:

I sat down with my family and discussed it … I was afraid to go to trial. I knew I would get 10 years if I lost… I was locked up for no reason. I’ve seen it happen to other people. I’ve seen it on the news. I just never thought it would happen to me. It was a very scary ordeal.

Both Parks and Oliver before him sued for their wrongful arrests. The New York Times reportedthat Parks sued the police, prosecutor, and City of Woodbridge for wrongful arrest, false imprisonment, and violation of his civil rights. According to Vice, Oliver sued the city of Detroit and the detective who botched the case. Parks’ lawsuit did not ask for damages, while Oliver’s sued for at least $12 million. Both cases make the point that the fault for the wrongful arrests lay not only with the facial recognition algorithms, but also with the detectives in charge for not doing enough due diligence.

In yet another case of what some might call AI-enabled racial profiling, a facial recognition algorithm barred Lamya Robinson onto the premises of a Detroit skating rink. The Verge reported in July this year that after the algorithm incorrectly matched Robinson with someone else, the rink removed her from the premises. Robinson had never been to the skating rink in question. Her mother was quoted as saying “to me, it’s basically racial profiling … you’re just saying every young Black, brown girl with glasses fits the profile and that’s not right.” Civil rights nonprofit Fight for the Future has been fighting for the ban of facial recognition in retail stores. Following this incident Caitlin Seeley George, the director of campaign and operations at Fight for the Future, stated in a press release:

This is exactly why we think facial recognition should be banned in public places … It’s also not hard to imagine what could have happened if police were called to the scene and how they might have acted on this false information.

Facial Recognition Should be Used with Care

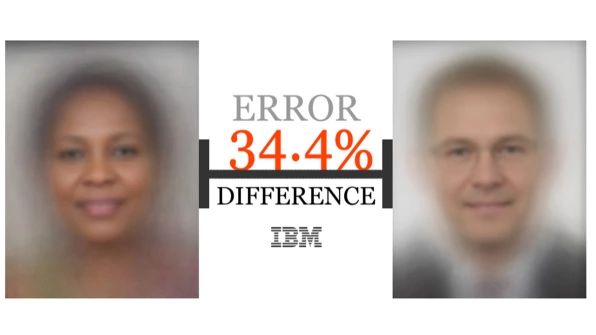

It is well-known that facial recognition systems do not work well for everyone. The 2018 Gender Shades project, spearheaded by researchers Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru, evaluated the accuracy of AI gender classification products. In their evaluation of commercial systems from IBM, Microsoft, and Face++, they found that all companies’ systems more accurately identified gender for male subjects than for female subjects. The disparity widened when they compared accuracy for whiter males (near 100% in all cases) and darker females (IBM’s and Face++’s systems had roughly 65% accuracy and Microsoft’s had 79.2%).

study.](/assets/img/briefs/wrongful-arrests/gender-shades.png)

A 2019 study from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) further buttressed Gender Shades’ arguments, finding empirical evidence for demographic disparities in the facial recognition systems they looked at. They found that false positives--where the algorithm incorrectly identified photos of two different people to be the same person--for African Americans and Asians were higher than those for Caucasians by factors of 10 to 100. Interestingly, some algorithms developed in Asian countries, which may have used more diverse datasets, did not show a dramatic difference in false positives.

Given the Gender Shades study and a litany of other research, it seems inevitable that algorithms will display some biases and defects. We should strive to make them better, but also consider how to use them given their faults. The case of Robert Williams demonstrates a striking failing in the use of an algorithm: the police who arrested Williams may have placed too much trust in the algorithm’s identification, and there were no processes in place to mitigate the impacts of that over-reliance.

According to the Detroit police report, investigators did not arrest Williams immediately, but included his photo in a “6-pack photo lineup” they showed to Katherine Johnston, an investigator who reviewed the surveillance footage that was shared with the police. Johnston then identified Williams as the suspect. On face, it seems as though *some *due diligence was performed on the part of the police, because humans were involved in the process that led to Williams’ arrest.

But this line-up story demonstrates both an over-reliance on the facial recognition algorithm and a process that left much to be desired:

Mr. [Brendan] Klare, of Rank One, found fault with Ms. Johnston’s role in the process. “I am not sure if this qualifies them as an eyewitness, or gives their experience any more weight than other persons who may have viewed that same video after the fact,” he said. John Wise, a spokesman for NEC, [a facial recognition provider,] said: “A match using facial recognition alone is not a means for positive identification.”

The fact that Johnston only watched surveillance footage of the incident and was asked to identify a suspect from the photo lineup months later introduces serious questions about the credibility of her identification. And, her choice might also reflect that he simply looked the most *similar to the shoplifter among the 6 images. Furthermore, as the *New York Times article points out, the police did not perform the full due diligence required to establish Williams as a probable suspect; they simply included his face in a lineup, rather than searching for other evidence that might have linked him to the shoplifting incident. Had they done so, this incident might never have occurred.

study.](/assets/img/briefs/wrongful-arrests/mugshots.webp)

Similar flaws in procedure are apparent in the investigations that led to Oliver’s and Parks' arrests. Parks was 30 miles away from the scene of the incident for which he was arrested, which he was able to prove, and while he resembled the photo of the suspect there are some clear differences that should have led to more questioning of the algorithm. In Oliver’s case, a quick look at a photo of the culprit would have shown that he and Oliver were not the same person: Oliver had faded sleeve tattoos on both his arms, unlike the phone thief. David Robinson, Oliver’s lawyer says the detective in their case blew it: “He certainly was in possession of a photograph of the real crook but for some reason wasn’t able to distinguish the difference between them.”

.](/assets/img/briefs/wrongful-arrests/oliver.png)

Oliver’s law-suit further states:

[Police relied] on failed facial recognition technology knowing the science of facial recognition has a substantial error rate among black and brown persons of ethnicity which would lead to the wrongful arrest and incarceration of persons in that ethnic demographic

Amidst calls for bans on facial recognition around the country, steps forward have been made. After police investigated Oliver’s case, a new policy governing the use of facial recognition software was put into place, which includes stricter rules on police use: “The technology is now only used as a tool to help solve violent felonies, Detroit police have said.”

Conclusion

Among the different AI technologies adopted in our daily lives, facial recognition algorithms are one of the most controversial and potentially one of the most impactful. Given the potential impacts of their use, it is vital that those developing and using facial recognition systems think very carefully about the limitations of those systems and how their use will affect people. There is an important ongoing debate about whether facial recognition systems should be allowed in the first place; there is a good argument that they can provide some social good, but many claim that they are still too dangerous to be used at all. Regardless of this debate, facial recognition systems are already being used every day, and their misuse has already harmed multiple innocent people. As adoption of this technology continues many more cases of this sort of harm are likely to happen, and so the shortcomings of these systems must be made clear to their users, and proper procedures must be put in place to mitigate potential for their misuse.