Examining Henry Kissinger's Uninformed Comments on AI

Another public figure with no expertise on AI issues sweeping, unfounded statements about it threatening humanity

Image credit: Photo from UPI, AlphaGo logo owned by DeepMind

What Happened

With AI having become as influential as it is today, leaders from all disciplines have been commenting about its potential impacts on society. Most recently, former Secretary of State and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger penned an article titled “How the Enlightenment Ends” in The Atlantic. In it, he issues grave warnings about the consequences of AI and the end of Enlightenment and human reasoning.

He begins by describing his amazement at a conference speaker’s presentation about AlphaGo, an AI agent that managed to defeat the world’s best human players of the popular strategy board game Go (see our perspective on the significance of AlphaGo in these two Skynet Today articles). Hearing of AlphaGo’s success, and of how it was achieved through an algorithm that relied on self-play rather than human guidance, leads him to ponder:

“What would be the impact on history of self-learning machines—machines that acquired knowledge by processes particular to themselves, and applied that knowledge to ends for which there may be no category of human understanding? Would these machines learn to communicate with one another? How would choices be made among emerging options? Was it possible that human history might go the way of the Incas, faced with a Spanish culture incomprehensible and even awe-inspiring to them? Were we at the edge of a new phase of human history?”

He then “organized a number of informal dialogues on the subject”, which “caused [his] concerns to grow”. They led him to believe AI may cause a “sweeping technological revolution whose consequences we have failed to fully reckon with, and whose culmination may be a world relying on machines powered by data and algorithms and ungoverned by ethical or philosophical norms.”

He argues for this prediction by way of analogy to how the printing press allowed the Age of Reason to supplant the Age of Religion. He proposes that the modern counterpart of this revolutionary process is the rise of intelligent AI that will supersede human ability and put an end to the Enlightenment. Specifically, after briefly acknowledging some possible positive applications of AI, he proceeds to discuss three areas of concern regarding the trajectory of artificial intelligence research:

- “AI may achieve unintended results.” He raises the concern of whether it would be possible to detect and correct improperly functioning AI systems, or whether mishaps would remain undetected and snowball catastrophically. 1

- “In achieving intended goals, AI may change human thought processes and human values.” Since AlphaGo used unprecedented moves that humans had not used before, he claims that its single-minded intent to simply win the game would change the game, as well as human thought and values. 2 Further, he postulates that if AI “learns exponentially faster than humans”, they would make more drastic mistakes as well, and then suggests that this might allow AI to be the arbiter for moral and ethical questions regarding these mistakes.

- “AI may reach intended goals, but be unable to explain the rationale for its conclusions.” He poses a number of questions about whether AI can “explain, in a way that humans can understand, why its actions are optimal”, whether AI’s decisions may “surpass the explanatory powers of human language and reason”, and “What will become of human consciousness if its own explanatory power is surpassed by AI, and societies are no longer able to interpret the world they inhabit in terms that are meaningful to them?” Certainly a concern filled with hefty, existential vocabulary.

The recurring idea here is simple, and not new: AI cannot be kept in check. He concludes with the idea that our age has “generated a potentially dominating technology in search of a guiding philosophy” responsible for the possible “transformation of the human condition”, and urging the importance of “relating AI to humanistic traditions”. However, beyond the three vague points of concern he raises, it’s largely unclear how AI technology is going to end the Enlightenment.

Nevertheless, with far-reaching claims and heavy rhetoric, his message elicited many responses.

The Reactions

Media coverage of the piece was light, but a handful of media outlets and content creators on YouTube wrote articles and posted videos summarizing and adding onto Kissinger’s points.

Few pieces were written in opposition to Kissinger’s, with the exception of Timothy Carone’s Scientific American article that declares that Kissinger falls under the umbrella of

“well-known and well-meaning people making pronouncements about existential threats when, in fact, none exist and there is no proof yet that they can exist”.

On social media platforms, the bulk of the responses came from AI researchers and other notable leaders in the field, who had lots of thoughts to share about the article. Most prominent was AI expert Yann LeCun’s response to the article on Facebook. He not only criticizes Kissinger’s misleading representation of the “informal gatherings”, noting that “I participated in one of those gatherings, which was anything but informal”, but also highlighted the critical “erroneous belief” present in Kissinger’s article regarding AlphaGo:

“On its own, in just a few hours of self-play, it achieved a level of skill that took human beings 1,500 years to attain. Only the basic rules of the game were provided to AlphaZero. Neither human beings nor human-generated data were part of its process of self-learning. If AlphaZero was able to achieve this mastery so rapidly, where will AI be in five years?”

He refuted the fear-inducing fallacy Kissinger committed with succinct certainty:

“As much as I would like to believe otherwise, the type of learning used in AlphaZero…does not take us any closer to human-level intelligence, or even cat-level intelligence…the kind of learning we need for AI to make progress in the real world needs to be of a very different kind.”

LeCun also responded to a comment on his post about the “old and overblown narrative” of AI taking over the world, and how the lay public can’t help but fear the consequences because the myths aren’t properly dispelled.

“I think this “old and overblown narrative” is a consequence of two things: 1- serious scientists not venturing into speculative futuristic predictions to preserve their credibility as serious scientists (nothing wrong with that). 2- non scientists, who are used to holding the levers of power in society, trying to maintain their diminishing control over things by telling scientists that they know nothing about the “real world”. They are the ones worrying about “robots taking over” because it’s their job to “take over”. But as we all know, this desire to take over is somewhat inversely correlated with intelligence.”

LeCun was far from the only AI expert to call out Kissinger for overstepping the boundaries of his area of expertise. On Twitter, AI researcher Oren Etzioni took a clear jab at Kissinger’s statement:

You know that the dialog about AI has "jumped the shark" when no other than Henry Kissinger pontificates about it with statements like "AI, by contrast, deals with ends" https://t.co/BvcX1VayGB Hey, Dr. Kissinger--do you want to hear my thoughts about the Vietnam War?

— Oren Etzioni (@etzioni) May 16, 2018

People from every discipline made some comments on Kissinger’s fear-mongering article, from social neuroscientists:

I think Henry Kissinger just found out about AI and this essay is just adorable https://t.co/W4B8EIjlpA pic.twitter.com/czRuuT74gt

— Adam J Calhoun (@neuroecology) May 19, 2018

To writers:

The Atlantic let Henry Kissinger write about the ethics of AI. Henry Kissinger has comprehensively failed at the ethics of being a human. AI is a long way from being so dangerous that it plans secret bombing campaigns against Cambodia, murdering more than 4,000 people.

— Mic Wright (@brokenbottleboy) July 9, 2018

To foreign ambassadors:

Henry Kissinger on AI makes as much sense as Graham Allison on China. Oversimplification sparkled with uninformed cliches (e.g. “ Yet driverless cars are likely to be prevalent on roads within a decade“. Unlikely). https://t.co/XDhMgmgT5L

— Jorge Guajardo (@jorge_guajardo) May 20, 2018

Some responses took a more humorous spin:

How about an article by an AI on the threat of Henry Kissinger? Should be easy to generate. https://t.co/aSP5iuUM2X

— Suresh Venkatasubramanian (@geomblog) May 16, 2018

Alarmingly, however, a search on Twitter for Kissinger’s message had a high proportion of international engagement, with messages sharing it in French, Spanish, and German among others. The message was indeed broadcast and shared worldwide. In fact, the First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, even shared the article as something to “get your intellectual juices flowing”:

If you want something non party political to get your intellectual juices flowing this Monday morning, I recommend this by Henry Kissinger on the philosophical questions that Artificial Intelligence poses for the human race. https://t.co/5COtL1vlY7

— Nicola Sturgeon (@NicolaSturgeon) July 9, 2018

And she wasn’t the only one to commend Kissinger for his writing. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis actually quoted the article in an embellished memo to our current President this May, urging him to create a national strategy for artificial intelligence:

“Mr. Mattis argued that the United States was not keeping pace with the ambitious plans of China and other countries. With a final flourish, he quoted a recent magazine article by Henry A. Kissinger, the former secretary of state, and called for a presidential commission capable of “inspiring a whole of country effort that will ensure the U.S. is a leader not just in matters of defense but in the broader ‘transformation of the human condition.’” Mr. Mattis included a copy of Mr. Kissinger’s article with his four-paragraph note.””

Other notable persons to commend include magazine editors and professors (with large follower counts):

If you read one thing today, it should be Henry Kissinger's article about #AI. Dude is 94, but I dare say he understands the implications of artificial intelligence better than most 25-year-olds I've met. https://t.co/REarPSLDmw

— Drew Prindle (@GonzoTorpedo) May 15, 2018

How the Enlightenment--and possibly human history--ends. Sobering piece by Henry Kissinger about the dangers of AI run amok. https://t.co/ABnPT6W4Ji

— Scott Stossel (@SStossel) May 15, 2018

Henry Kissinger (!!!)in fine form, reflecting on AI. I found it insightful and quite novel. A must read https://t.co/MUdEPMqzmc

— Luis Garicano (@lugaricano) July 8, 2018

It’s clear that, much to the exasperation of AI researchers, Kissinger sparked a lot of debate and controversy online.

Our Perspective

AI isn’t going to overthrow humanity anytime soon. In fact, it’s still far from undertaking many complex tasks that we are building them to do. Just because AI techniques were used to to defeat humanity’s best at Go does not mean it we are even close to a “‘generally intelligent’ AI”, as Kissinger implied.

Kissinger’s article is based on the classic ‘slippery slope’ mistake that leads to the overestimation of AI technology. As usual in such cases, it is mostly based on speculation informed only by Kissinger’s own opinion and the limited education that “informal gatherings” could provide. However, despite being clearly speculative in nature, the article nevertheless fanned the flames of AI fears likely already present in many of its readers.

Not only were his claims unbacked, but they were also wrong: the central argument of the article suggests that AI techniques are evolving more rapidly than we can control (among other overreaching claims), which simply isn’t true. To see why, let’s address Kissinger’s three concerns.

- “AI may achieve unintended results.” As with any technology, this may be true, but the trial and error will not spin out of control and be irreversible the way Kissinger insinuates. Once mistakes are made, they are fixed, as with experiments in any scientific discipline. It’s not dark magic.

- “In achieving intended goals, AI may change human thought processes and human values.” This simply takes things too far. In most applications of AI today, algorithms do not have the intelligence and sophistication to change human thought. Any shift in human values as a result of developing AI technologies is due to human behavior and conscious choice: which tasks we use machine learning to solve and which problems we prioritize over others. As with any burgeoning technology, we must take the responsibility for what we choose to use these tools for, rather than blaming it on the emergence of the technology.

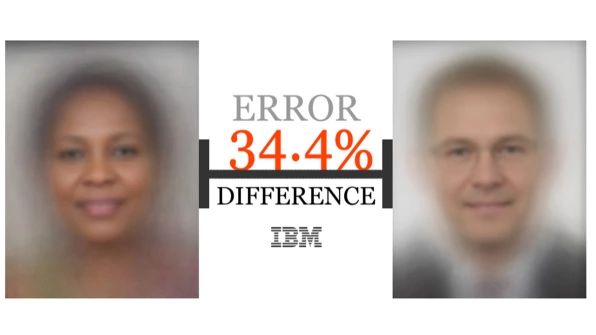

- “AI may reach intended goals, but be unable to explain the rationale for its conclusions.” This is indeed a relevant concern, but significant work is going into addressing it. A large body of AI research focuses on the interpretability of neural network systems, and several publications have the aim of explaining the inner workings of neural network building blocks and parameterizations. In addition, AI algorithms are designed not to make decisions on our behalf so much as to be an aid in making decisions. As seen in the recent blunder of Amazon’s facial recognition software that mistook members of Congress for criminals, making decisions purely based on AI systems is neither reliable nor supported. We’ve got a long way to go before that is a realistic possibility.

In addition, Kissinger failed to recognize some nuances regarding the state of AI technology today. Here are a few key points:

- AI algorithms today do not “[deal] with ends” and “[establish their] own objectives”; in fact, the exact opposite is true. AI and machine learning algorithms complete assigned tasks by optimizing a particular objective that was chosen by a human. The algorithms themselves are not at all self-sustaining or autonomous and are very much under human control.

- AI technology does not threaten human cognition and civilization. According to the Financial Times, machine learning currently has already stimulated U.S. economic and productivity growth. AI is also not even close to achieving general intelligence capable of deep reasoning or moralizing, and is rather currently built to streamline human tasks and aid economic growth3. It thus simply isn’t logical that it would revolutionize our way of thinking or moral philosophy the way Kissinger insists.

- The AI community is in fact very concerned with ethics and constantly discusses and promotes it. Scientists are not blind to society, and it is insulting and degrading to suggest so, as Kissinger did here. Universities doing research in the field actively educate students on the importance of being aware of the impact of the technology they create, and leaders in AI are indeed aware of the implications of new technologies (see Margaret Mitchell’s TED Talk on this subject). In fact, researchers like Miles Brundage dedicate their entire lives to studying the societal implications of AI technology. It is true that thinkers in all disciplines, including the humanities, should be involved in establishing these crucial guidelines, and those in tech should be educated on ethics and privacy concerns. But it is wrong to assume that academics in AI are relentlessly optimizing AI in a vacuum, at all costs, without concerns about its impact. This notion is blatantly false.

Yann LeCun’s public criticism of this article is commendable. Those not in the scientific community can’t be expected to know the state of the science and how much it has advanced, and sensational news headlines don’t help with that misperception. The scientific community must be transparent and vigilant in maintaining an accurate, factual account of AI progress to keep the public well-informed. And the public should listen to the experts, not the speculators.

Of course, global leaders also have the duty to spread knowledge and keep the public properly informed. Kissinger’s article didn’t accomplish this. For instance, in comparison to Kissinger’s fear-inspiring verdicts, President Barack Obama’s public comments on AI technologies 4 were more reasonable.

"Generalized AI is worth thinking about because it stretches our imaginations and it gets us to think about our core values and issues of choice and free will that actually do have significant applications for specialized AI." - @BarackObama pic.twitter.com/VFhJsMXuIq

— Lex Fridman (@lexfridman) March 21, 2018

The bottom line: prominent leaders need to be particularly careful when issuing messages on topics that aren’t their expertise. AI is already highly misrepresented in mainstream media, and leaders should be helping to rectify, rather than exacerbate this issue.

TLDR

Henry Kissinger issued an ominous message in The Atlantic regarding the consequences of rapidly advancing AI and its potential to overthrow humanity, take over the world, and nullify human knowledge. The article, with little evidence and overreaching generalizations, cites common misconceptions about the state of AI research. It therefore elicited indignant responses and backlash from the AI community, which attempted to correct his misinformed representation of AI. We urge politicians, and people with the ability to influence public perception in general, to be more cautious with their public pontificating about AI to avoid exacerbating already widespread misunderstanding about the field.

-

He cites the chatbot Tay that was intended to produce friendly conversation in the manner of a teenage girl, but instead issued inflammatory remarks. ↩

-

Kissinger challenges the idea of educational chatbots and machines a step further by arguing that they would be used in the classroom to teach children, including subjects such as philosophical principles. He postulates these machines would shape children’s thoughts in a pervasive manner. ↩

-

A Bloomberg article further explains - “machine learning will revolutionize white-collar jobs in much the same way that engines, electricity and machine tools revolutionized blue-collar jobs…machine learning tools will allow workers to skip some mental tasks and apply their brain power to only a select few things.” ↩

-

In short, these comments correctly described generalized AI as being (as far as we can tell) a long way away and pointed out there are many issues to addressed with the narrow AI that we do already have ↩