Retraining as a Response to Automation — Promising, but Only if Done Right

Effective worker upskilling requires a broad approach that puts more value on human capital.

Image credit: CNBC via YouTube

Background

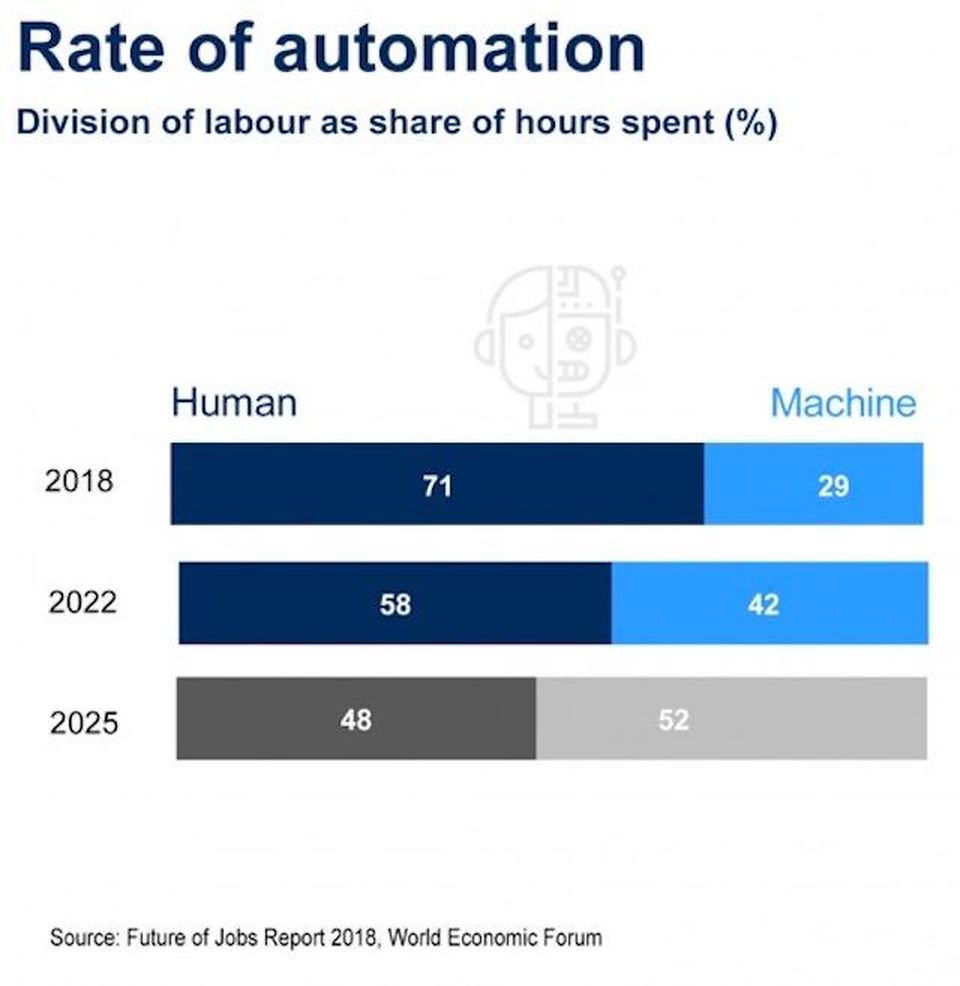

The recent rise of technology and AI-enabled automation (AI Automation) presents what many perceive as scary prospects for the job market. While increasingly powerful technology may revolutionize society in a number of positive ways, from personalized services to making products more affordable [HBR, Forbes, Adobe]: “beneath the surface of innovation a current of economic disenfranchisement threatens to sweep society away”. There is plenty of debate over this–one major counter-argument points out that while the First Industrial Revolution wiped out a number of jobs in its own era, things returned to normal after a period of time. But the story that the often-cited “AI Revolution” will be different, since AI Automation may displace workers faster than they can adapt and change to new jobs, is a compelling one.

In response to the potentially drastic ways automation may change the nature of jobs, companies and firms have already begun upskilling their workers. Many solutions to automation-induced labor displacement have been proposed and experimented with in the past, and upskilling in particular is a popular option. Upskilling is when companies invest in training programs that teach workers new skills, so that they may “enhance their value to the organization”. In this editorial, we will discuss the upskilling of workers as a response to AI Automation and assess its effectiveness as a counter-strategy. In particular, we will discuss how the United States might develop an upskilling-centered strategy to provide security for workers in a fast-changing job market and work environment.

AI Automation will displace some jobs and create others, but the displacement will affect some sectors and communities much more than others. We’ve previously covered this topic in depth, so we will only discuss the situation briefly here. The Brookings Institute suggests that automation can replace labor in a number of ways, including substituting entire jobs, substituting particular tasks, and complementing labor. Overall, automation will affect occupations in “virtually all occupational groups in the future but the effects will be of varied intensity–and drastic for only some.” To contextualize, McKinsey says only five percent of occupations could be fully automated by current technologies, while about half of the activities carried out by workers can be automated. Besides varying across occupation, effects are likely to vary across regions and demographics, and “men, youth, and under-represented groups will be the most impacted among demographic groups” [Brookings]. In sum, changes to the workplace due to automation may not be as drastic or significant as many fear, but they will certainly occur.

Current Upskilling Efforts

In response to automation’s impacts, upskilling workers appears to be the most popular course of action contended for today. Its premise is that because the skills needed by jobs of the future will be different, workers should develop new skills that will prepare them to find work in such a changing environment. According to McKinsey, particular changes will likely include a decline in demand for physical/manual skills and higher demand for “advanced technological skills” (i.e. programming), “higher cognitive skills” (i.e. creativity, critical thinking), social and emotional skills, and the ability to work cooperatively with technologies that automate tasks (i.e. operating a robot to move boxes). Countries like the UK and Sweden are investing heavily in retraining, and many corporations have already begun embracing the strategy because of the widespread belief that retraining workers is indeed the best solution to automation.

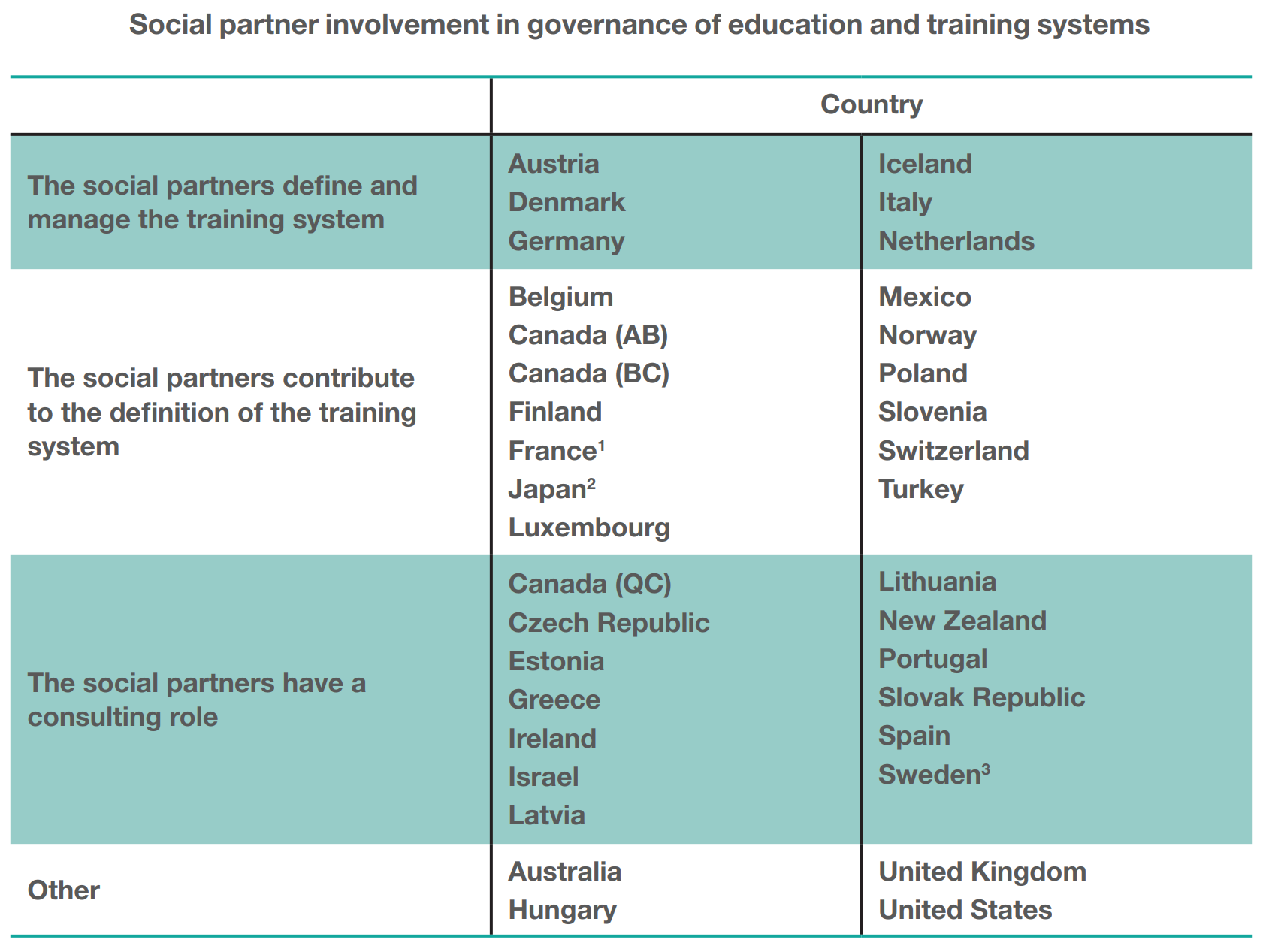

In particular, Amazon has received acclaim in the wake of its July announcement that it plans to spend $700 million dollars to retrain a third of Amazon workers as part of its” Upskilling 2025” initiative. A more dated example from 2013 is AT&T’s efforts to re-skill their entire 280,000 person workforce). While such efforts seem commendable on the surface, an article by Gizmodo discusses a number of important issues and considerations that could render upskilling efforts less effective than they seek to be. Problems include that re-training efforts aren’t seen by workers as effective, occur outside work hours, are unpaid, and don’t guarantee a job at the end. The benefits of these efforts skew towards savvier and more well-educated workers, and the structuring of programs to maximize benefit for companies instead of particular workers renders re-training efforts genuinely ineffective for many workers. Gizmodo concludes that in order for any upskilling program to be truly effective, it must give workers a seat at the table–otherwise it risks failing to serve those who need it most. This might look like the OECD’s model, which helps determine relevant priorities and the structure of retraining through a “strong working relationship between employer organisations and trade unions on issues of adult learning policy.”.

Main Questions

The examples so far highlight a few important questions:

- Can retraining programs be effective, and what would effective programs look like?

- How can large companies make their existing retraining programs more effective?

- If retraining is truly a good idea, how can we incentivize:

- investments in retraining programs, and

- assurances that those programs are effective?

Potential Strategies

MIT’s Work of the Future Report by the MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future discusses where the U.S. currently lacks in regard to providing its workers with important skills and opportunities: while almost all developed countries have experienced job polarization:

most have done more than the United States to counter these undercurrents by investing in worker skills, strengthening social safety nets where needed, and incentivizing private-sector firms to augment labor rather than simply displace it”.

This lack of investment in and attention to human capital has both stoked worker polarization and created a lack of incentives for private firms to substantially invest in workers without elite education. However, the report describes a positive outlook for the future

Countries that make well-targeted, forward-looking investments in education and skills training should be able to deliver middle-skill jobs with favorable earnings and employment security to the vast majority of their workers–and not exclusively those with elite educations”.

Also noting that current technology and most technology for the foreseeable future will automate tasks and not entire jobs, the Task Force encourages optimism in the prospects of future workers if countries such as the United States do a good job of making investments in education and skills training. Before settling on retraining programs as the way forward however, it will be important to assess both possible alternatives and the capacity of worker training to address the challenges it seeks to. Let’s recount the fundamental issues that affect workers in the face of automation:

- More sophisticated technology and the resulting automation of tasks could lead to job loss

- Many fast-growing and low-risk jobs require advanced education and broad expertise

- Workers who are at risk of replacement may have a difficult time switching jobs due to a skills gap, money, or location

Any potential solution to automation-induced challenges must address the issues above. That is, it must either stem job loss, create jobs that do not require advanced education and are not at risk due to automation, or address the skills gap.

Evaluation of Alternative Responses

Stemming job loss enough to counteract changes in the workplace due to AI will likely be difficult. While it may take time for AI systems to be fully integrated into the workplace, firms will likely follow incentives to reduce costs and increase productivity where they can. The impacts will not be small, either. Forrester vice president Huard Smith predicts that “73% of all cubicle-related jobs… like data entry… will be automated by 2030, equating to over 20 million jobs eliminated” while “38% of location-based jobs”, such as grocery store clerks, will also be eliminated, amounting to 29.9 million positions eliminated. It’s worth noting that these predictions are unusually high, but predictions about the loss of jobs to continued technological progress do vary greatly. While different global experts on economics and technology don’t appear to be on the same page about predictions of job loss, understanding and preparing for the worst possible outcome may not be a bad idea. It’s hard to know just how fast job losses will hit, but the general attitude towards workers’ chances of adapting seems pessimistic.

With these dire predictions in mind, Forrester supports corporate training programs and making sure workers are fully aware of the impact that AI will have on their jobs — he projects that AI will displace 29% of U.S. jobs while creating the equivalent of only 13% [Fortune]. Not all predictions are so dire, and some even predict that AI will result in a net creation of jobs, but the concern still remains that the nature of the workplace and the types of jobs that will exist in the future will likely be different from those today, so those hoping to participate in the workforce decades from now will have to find a way to adapt to the changes.

While AI will displace many jobs, ones involving more menial tasks, such as cashiers, likely won’t be completely eliminated in the near-future. While self-checkout machines have become pervasive, human workers are still required to oversee the machines if they malfunction and to help confused shoppers, among other things. The nontrivial cost of adapting new technology means that it will take time to phase out certain jobs, if ever. Even though seventy-five percent of executives believe that their business will risk failure in a matter of years if they don’t scale AI, adopting AI is not a simple process and will take some time. However, hoping that jobs that can be automated will stay around longer than necessary does not provide a viable long-term solution.

A Case for Retraining

As such, it seems that the most fruitful issue to tackle is that of workers’ training. The inevitable race towards AI adoption and its consequent impact on the workplace make retraining workers a natural option. Not only does it appear to be the only choice left by exhaustion, but in considering the three key issues we outlined above, it appears to be the most promising option if it can be done effectively. We noted that issues of location and money may also hinder job mobility, but if workers do not have the proper training and ability to take on new jobs, fixing these two issues will not make a difference.

However, complete retraining and skill redevelopment may not be necessary in all cases–an article by Atlassian points out that in order to remain useful while AI continues to automate tasks, workers can focus on the more interactive and managerial aspects of their jobs. While AI can automate administrative tasks already, people who know how to interact with both humans and technology have higher chances of remaining employed. This being said, workers such as cashiers or those who focus mostly on either human interaction (cashiers and sales representatives, for instance) or technology (such as IT professionals in lower-skill roles that involve tasks like data entry) will need to boost their skillset in order to remain a valuable asset in their workplaces. As should be evident, that boost will likely not look the same for any two workers.

Furthermore, the impact of AI will be different from those of its predecessors. While low-skill workers were impacted by the automation of tasks in the past, research from Stanford finds that workers with bachelors’ degrees are more likely to be impacted by AI than those with high school degrees. According to the MIT Technology Review, “Market analysts, sales managers, programmers, financial advisors, and chemical engineers are near the top of the hit-list.” In particular, highly specialized jobs and ones involving more menial work are at risk. The Stanford study points out what doctors and nurses, whose works involve a substantial interpersonal component, are not completely at risk even if some of their tasks can be automated. More specialized medical occupations such as medical technicians will be highly exposed to AI-enabled automation, while lower-skill healthcare occupations such as home health care aides are less exposed because of the variable physical and interpersonal activities they perform. While this example shows that AI’s impacts on the labor market will likely differ considerably from those of prior automation, the relative safety of jobs such as health care aides does not imply that there will be job growth to counteract the loss of jobs due to automated tasks.

Our Recommendations

So what is to be done? The above discussion and current research indicates that interestingly, those with bachelors and masters degrees will be at relatively high risk of displacement by AI. However, it is acknowledged that certain technical tasks (such as developing AI) and interpersonal tasks are currently at low-risk. Therefore, it appears that workers who have general expertise (are not too specialized) and strike a balance between technical and interpersonal competence will fare better in the future job market. Workers whose jobs risk being replaced entirely will need to learn new technical skills, while skilled workers who are at risk will need to develop broad expertise.

Therefore, we recommend that retraining programs be pursued, but that they are structured with two points in mind. First, high specialization can lead to higher exposure to automation in some cases–workers should be trained in a wide range of technical competencies because it is difficult to know which tasks will be automated in the future, and such general training will make workers more likely to be able to work along with AI. Second, interpersonal and managerial skills involving tasks that interact with other people are considerably more difficult for AI to automate (whether it’s the actual interaction or making people comfortable with the idea of interacting with AI as opposed to people). Retraining programs should give sufficient emphasis on interpersonal skills to more effectively protect workers’ future job prospects.

Areas of Focus for Retraining Programs

In response to our first point, it appears that the right retraining programs could serve as a useful forward-looking investment. While increasing investment in human capital will certainly be a boon, the Task Force points out that alone, such programs will be inadequate. This is already demonstrated by the discontent with retraining programs such as Amazon’s: workers feel as though they aren’t learning useful skills and don’t have a seat at the table in making decisions about these programs, for instance. Further, a combination of public and private efforts will be crucial to not only ensure that workers have the skills to keep working, but also to create an environment that encourages continued investment in their economic future. To meet the technology and workforce challenges that are increasingly confronting the world’s industrialized economies, governments and companies must do more than upskilling alone. The Work of the Future report recommends adopting an approach that looks further than just retraining, public and private sector actors can help “shape the work of the future towards greater economic security for workers, higher productivity for firms, and broader opportunity for all.” The report also suggests four broad areas of focus–the first three are relevant to our discussion:

- Rebalancing fiscal policies away from subsidizing investment in physical capital and toward catalyzing investment in human capital

- Restoring the role of workers as stakeholders, alongside owners and stockholders, in corporate decision making

- Fostering technological and organizational innovation to complement workers

We will now discuss how these three areas of focus are relevant to the three questions we posed. The most effective upskilling programs are the ones that exist within a larger context that supports the goals of upskilling by focusing on more than just the retraining of workers. The rebalancing of fiscal policy plays an important role in both incentivizing investment in physical capital (e.g., retraining workers) and in allowing retraining programs to be effective. We have already described how retraining programs can be effective in theory, but without the proper incentives to invest and properly structure the training programs, no amount of planning will allow them to actually achieve their purpose.

Existing programs can become more effective by addressing workers’ concerns, and broader policies that share the goals of upskilling can provide incentives and checks of effectiveness. Such checks of effectiveness would consist of evaluation of the outcomes of re-training participation. This might include surveying worker satisfaction with re-training programs and linking accreditation and the result of inspections to funding decisions, strategies already implemented by Denmark and Belgium.

In addition to private sector investments like Amazon’s and AT&T’s, public sector investments will be very important to make sure that the general workforce receives the intended benefits of such programs. Community colleges, sectoral training and apprenticeship programs, and online learning programs as three major venues that could play an important role. Community colleges have the advantage of adaptability to local market needs, sectoral approaches can adapt to local situations, and online courses have the ability to reach wide groups of people. Some avenues for retraining in places like community colleges already exist, showing that some of these strategies will not require substantial changes.

In addition to focusing on policies and the roles of workers, private firms will do well to follow the Work of the Future report’s advice regarding fostering workplace innovation. Although workers might be well-equipped with useful skills and are active participants in the construction of retraining programs, AI will need to be integrated into the workplace and complement workers’ skills. This will enhance productivity far more than adopting AI without any experimentation or thought as to how it will interact with people in the workplace.

Takeaways and Conclusions

We believe an effective retraining strategy will incorporate a combination of public- and private-sector resources. On one hand. private firms make continued efforts to retrain their workers, but they will need to modify the shareholder paradigm which acts solely to maximize shareholder profit. By taking responsibility for the interests of employees and bringing technological developments in concert with workplace skills development, companies can prepare workers for the inevitable changes in work. On the other hand, public investments in the three venues discussed earlier (community colleges, apprenticeship programs, and sectoral training programs) can aid people who have not yet joined the workforce, those in between jobs, and workers who need additional resources for retraining.

The change from shareholder values will be crucial and represents a major paradigm shift in how American companies treat workers–companies like Amazon will have to re-examine where workers’ interests fit in with their priorities. However, as the Work of the Future report points out, the reasons for this are not unchangeable. Because U.S. fiscal policies currently subsidize investment in physical capital such as real estate, there is little incentive for companies to treat their employees as stakeholders. A policy shift towards subsidizing investment in human capital holds the promise of incentivizing companies to invest more in retraining their workers effectively. In general, improvements in existing upskilling programs can be effectively motivated by changes in policy towards a system that more highly values human capital.

Upskilling indeed has promise as an effective countermeasure to automation-induced job insecurity and market changes. A combination of public- and private-sector efforts have the potential to provide numerous means for workers to re-train and educate themselves in order to continue workforce participation. However, this comes with a number of caveats: if appropriate policies and programs are not adopted, the U.S. risks losing out on both helping its workers prepare for economic changes and reaping the benefits of continued technological progress. The U.S. should prioritize policies with the following goals in mind:

- Providing incentives to invest in human capital

- Providing incentives to distribute benefits of retraining and education investment to workers of all skill levels

- Increasing public-sector efforts to effectively re-train and upskill workers in addition to existing private-sector programs

- Involving workers/unions more effectively in the retraining process, listening to and acting on their stated needs and feedback

- Providing safety nets and paths to finding new jobs for laid off workers

We believe this multi-pronged approach presents an effective approach in helping workers transition during an era of fast-paced workplace changes enabled by powerful automation. Countries like Sweden, Austria, and Germany can serve as effective role models, and many studies also advise a broad approach. These include reports from the MIT Future of Work Task Force, the Aspen Institute, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, and McKinsey. If both public and private groups in the U.S. heed advice and consider adopting different fiscal and policy approaches, there is a real chance that the prospects for workers in our country will look far more exciting than concerning.