AI Coverage Best Practices, According to AI Researchers

AI researchers often bemoan low quality coverage of their field; here are their recommendations.

Interest in Artificial Intelligence (AI) has skyrocketed in recent years, both among the media and the general public. At the same time, media coverage of AI has wildly varied in quality – at one end, tabloid and clickbait media outlets have produced outrageously inaccurate portrayals of AI that reflect science fiction more than reality. At the other end, news outlets such as The New York Times or Wired have had specialized reporters such as Cade Metz and Tom Simonite who consistently write well-researched and accurate portrayals of AI. But, even responsible media coverage can inadvertently (and often unintentionally) propagate subtle misconceptions of AI through choice of wording, imagery, or analogy.

As AI researchers, we are both invested and sensitive to how AI is portrayed in the media. In this article, we suggest a list of best practices for media coverage of AI, some of which may not be obvious to people without a technical background in AI. In being a set of best practices, this list will not be representative of what even we as researchers always do, but rather principles to keep in mind and try to stick to (and ignore as needbe according to good judgement). The list is inspired both by our own observations, and the observations of the AI researchers we surveyed online and at the Stanford AI Lab. We hope it will be useful to journalists, researchers, and anyone who reads or writes about AI.

- Do: Be careful with what “AI” is

- Don’t: imply autonomy where there is none

- Do: make clear what role humans have to play

- Don’t: state programs “learn” without appropriate caveats

- Do: emphasize the narrowness of today’s AI-powered programs

- Do: avoid comparisons to pop culture depictions of AI

- Don’t: cite opinions of famous smart people who don’t work on AI

- Do: make clear what the task is, precisely

- Do: call out limitations

- Don’t: ignore the failures

- Do: present advancements in context

- Conclusion

Do: Be careful with what “AI” is

First and foremost, we would like to emphasize being careful with what “AI” actually means. Let’s get the obvious out of the way: present day AI systems have almost nothing to do with The Terminator or similar science fiction concepts, and AI researchers are almost universally annoyed to see stories with badly chosen stock photos implying that is the case.

So, what then is AI? AI researcher Julian Togelius addresses this question well in his blog post “Some advice for journalists writing about artificial intelligence”:

Keep in mind: There is no such thing as “an artificial intelligence”. AI is a collection of methods and ideas for building software that can do some of the things that humans can do with their brains. Researchers and developers develop new AI methods (and use existing AI methods) to build software (and sometimes also hardware) that can do something impressive, such as playing a game or drawing pictures of cats.

Though this may seem like an uncontroversial point, much AI coverage gets this wrong in multiple ways, and so we will unpack each way independently in the recommendations that follow.

Don’t: imply autonomy where there is none

Dear world (CC @businessinsider, @Hamilbug): stop saying "an AI". AI's an aspirational term, not a thing you build. What Amazon actually built is a "machine learning system", or even more plainly "predictive model". Using "an AI" grabs clicks but misleads https://t.co/0kdTLBsrHJ

— Zachary Lipton (@zacharylipton) October 11, 2018

One implication of the above definition is that it is misleading to say, for example, “An Artificial Intelligence Developed Its Own Non-Human Language”, since AI is not a single entity but rather a set of techniques and ideas. A correct usage is, for example, “Scientists develop a traffic monitoring system based on artificial intelligence”. As Veteran roboticist and AI researcher Rodney Brooks similarly states in his “7 Deadly Sins of Predicting the Future of AI”:

Some people refer to “an AI”, as though all AI is about being an autonomous agent. I think that is confusing, and just as the natives of San Francisco do not refer to their city as “Frisco”, no serious researchers in AI refer to “an AI”.

This may seem like a nit-picky point, but it’s part of a broader truth that is important to understand: today’s AI systems have close to no autonomy whatsoever in what they do. In saying “An artificial Intelligence” there is the linguistic implication of “An intelligence” and therefore an autonomous agent. This is not at all what AI-powered applications are today. Rather, they are just that: software applications, developed with the aid of AI algorithms but otherwise no different than the browser you are currently using to read this article – software that takes in input and produces output as specified by a human programmer. As one responder to our survey noted:

Systems are complex and their actions are difficult to interpret. There is research done in that field, but there is still a long way to go. But as with any other technology we use it as soon as it kind of works, even if there are well-known risks (like nuclear power) and uncertainties. The term AI attributes unexpected system behavior (i.e. a Tesla car suddenly stops with no apparent reason) to a *conscious decision* of “The AI” instead of a not-yet understood behavior of a complex technical system.

…

Bottom line: The term AI suggests that misbehavior of “AI” systems is a *conscious decision* of “The AI”, when instead the problem is that humans use technical tools which they built but do not yet fully understand and control, just like any other technology.

The last point here really gets to the bottom of the problem, as another responder also pointed out:

Anthropomorphism. Examples would be things like “IBM taught its AI to diagnose diseases” instead of “IBM wrote a computer program to diagnose diseases”. There is no single “IBM AI” that is being taught to play Jeopardy and also to diagnose diseases. They are just writing a bunch of different programs. Furthermore, although the technique of “Machine Learning” includes the word “learning”, using the word “taught” makes it sound like the computer is learning the way people do. But ML is very different from human learning. A better phrasing would be, “IBM ran a machine learning algorithm on a large database of medical records to create a system that can diagnose diseases”.

Do: make clear what role humans have to play

The above point about AI-powered systems having no real autonomy has a major and often overlooked implication: humans have a huge role to play in getting them to work. Headlines often say things such as “X’s AI Taught Itself How to Y”, which implies humans ‘merely’ got the AI algorithm together and let it run; when in fact, a huge amount of human thinking and effort always goes into making progress on new challenging applications of AI. For example, the recent story about OpenAI getting a robot hand to solve a rubik’s cube (when given the steps to get it to a solved state) was covered with a headline such as “This robotic hand learned to solve a Rubik’s Cube on its own — just like a human”, despite the project involving a huge amount of human effort as we made clear in our coverage.

Julian Togelius once again has points relevant to this one in his blog post:

Keep in mind: Much of “artificial intelligence” is actually human ingenuity. There’s a reason why researchers and developers specialize in applications of AI to specific domains, such as robotics, games or translation: when building a system to solve a problem, lots of knowledge about the actual problem (“domain knowledge”) is included in the system. This might take the role of providing special inputs to the system, using specially prepared training data, hand-coding parts of the system or even reformulating the problem so as to make it easier.

Recommendation: A good way of understanding which part of an “AI solution” are automatic and which are due to niftily encoded human domain knowledge is to ask how this system would work on a slightly different problem.

Don’t: state programs “learn” without appropriate caveats

One response to the above point may be to argue that many of today’s most prominent and powerful AI techniques stem from “Machine Learning” (a subfield within AI as a whole, with “Deep Learning” being a subset of Machine Learning), so if there is “learning” involved isn’t it fair to imply some degree of autonomy or agency? In short, we don’t think so. Rather, it is even more important to make clear the distinctions between the specific AI algorithms being used and human-like learning.

Using a word such as “learning” may invoke the idea of an intelligent autonomous agent, when the truth is that applying Machine Learning algorithms today mostly involves curating datasets of input and output data pairs and optimizing a program to map such inputs to their appropriate outputs. The program has no choice in the dataset, in its own structure, or when or how it is run. Thus, saying a program “learned” something without emphasizing this has almost nothing to do with how humans learn and involved no autonomy on the program’s part could significantly mislead readers. In general, as one responder to our survey suggested:

Be careful with vocabulary that is intuitive, as our intuitions about human learning and behaviour are a poor fit for AI systems (an issue that is not helped by the way some terms are used in the AI literature).

It’s true that we AI researchers are often the ones who make us of intuitive, but misleading, word choices in the first place. But, at least AI researchers are cynical enough not to take such words at face value; those without insight into the inner workings of modern day AI might imagine these words to mean much more profound things than they do. Comparisons to human learning or development should therefore be avoided even more. Rodney Brooks likewise highlights this in his blog post:

Words matter, but whenever we use a word to describe something about an AI system, where that can also be applied to humans, we find people overestimating what it means. So far most words that apply to humans when used for machines, are only a microscopically narrow conceit of what the word means when applied to humans.

Here are some of the verbs that have been applied to machines, and for which machines are totally unlike humans in their capabilities:

anticipate, beat, classify, describe, estimate, explain, hallucinate, hear, imagine, intend, learn, model, plan, play, recognize, read, reason, reflect, see, understand, walk, write

For all these words there have been research papers describing a narrow sliver of the rich meanings that these words imply when applied to humans. Unfortunately the use of these words suggests that there is much more there there than is there.

This leads people to misinterpret and then overestimate the capabilities of today’s Artificial Intelligence.

Do: emphasize the narrowness of today’s AI-powered programs

A corollary to the above point is that most of today’s Machine Learning-based programs can be characterized as doing just one sort of thing: mapping one type of input to another type of output. This is an example of “narrow AI”, meaning AI-powered systems that can only do one task as opposed to a wide variety of tasks. Another issue with saying “an intelligence” with respect to an AI-powered program is that as humans we are generally surrounded by examples of “general intelligence” – other humans – and so may assume the same of the program. Avoiding that misunderstanding is crucial, and it is another reason to use terms such as “AI-based program” or “AI-powered software” to call forth the right sorts of associations in readers without expertise in AI.

"Generalized AI is worth thinking about because it stretches our imaginations and it gets us to think about our core values and issues of choice and free will that actually do have significant applications for specialized AI." - @BarackObama pic.twitter.com/VFhJsMXuIq

— Lex Fridman (@lexfridman) March 21, 2018

This point is also made well by Julian Togelius in his blog post:

… you can safely assume that the same system cannot both play games and draw pictures of cats. In fact, no AI-based system that I’ve ever heard of can do more than a few different tasks. Even when the same researchers develop systems for different tasks based on the same idea, they will build different software systems. When journalists write that “Company X’s AI could already drive a car, but it can now also write a poem”, they obscure the fact that these are different systems and make it seem like there are machines with general intelligence out there. There are not.

And by Rodney Brooks:

Here is what goes wrong. People hear that some robot or some AI system has performed some task. They then take the generalization from that performance to a general competence that a person performing that same task could be expected to have. And they apply that generalization to the robot or AI system.

Today’s robots and AI systems are incredibly narrow in what they can do. Human style generalizations just do not apply. People who do make these generalizations get things very, very wrong.

Do: avoid comparisons to pop culture depictions of AI

Despite today’s uses of AI all falling into the “narrow AI” categorization, by far most pop culture depictions of AI focus on more human-like general AI. After all, it’s boring to focus on a computer program executing it’s human-written instructions, and fun to consider the implications of computer programs that have human-level or greater intelligence. It’s certainly okay for artists to ponder the implications of general AI, but because of this discrepancy between pop culture AI and real world AI, we would recommend generally avoiding comparisons between the two (unless the comparison is to point out how they strongly contrast).

Don’t: cite opinions of famous smart people who don’t work on AI

One especially complicated aspect of covering AI, as opposed to other technical subjects, is the long history of pondering about it in Science Fiction. While interesting, such speculations are also completely disconnected from the present day reality of AI, and say little about it. The same is true of the concern many famous smart people (Steven Hawking, Bill Gates, Elon Musk, etc.) have expressed about the threat of superhuman AI to humanity: these perspectives are speculations that are completely disconnected from anything factual about present day AI. As Rodney Brooks has said:

“TC: You’re writing a book on AI, so I have to ask you: Elon Musk expressed again this past weekend that AI is an existential threat. Agree? Disagree?”

“RB: There are quite a few people out there who’ve said that AI is an existential threat: Stephen Hawking, astronomer Royal Martin Rees, who has written a book about it, and they share a common thread, in that: they don’t work in AI themselves. For those who do work in AI, we know how hard it is to get anything to actually work through product level.”

Nevertheless, these speculations have drawn much coverage in articles such as Stephen Hawking Fears A.I. May Replace Humans, and He’s Not Alone and Henry Kissinger Warns That AI Will Fundamentally Alter Human Consciousness (the latter of which we covered in “Examining Henry Kissinger’s Uninformed Comments on AI”). Although it may seem like such coverage does no harm, it may lead people to think such an AI apocalypse is an actual possibility, and to misunderstand or ignore the very real concerns about present day AI. This was recently expressed by neuroscientist Anthony Zador and AI expert Yann LeCun:

“they [speculations about supertintelligent malevolent AI] distract from the more mundane but far more likely risks posed by the technology in the near future, as well as from its most exciting benefits.”

Of course, this does not mean only AI researchers should only ever get to comment about the state of AI. Public figures such as Barack Obama and Gary Kasparov are good examples of ‘famous smart people’ whose comments on AI are grounded in fact and accurate. But, as a general rule (which are all these best practices are, and all are subject to being overriden by good judgement) such comments have tended to confuse moreso than clarify about the state of present day AI, and so we advise caution when citing the opinions of non AI researchers.

Do: make clear what the task is, precisely

The above set of recommendations have to do with one’s broad understanding of AI, and our next set of recommendations will discuss the more specific details that one needs to pay careful attention to and ideally let the reader know when covering AI.

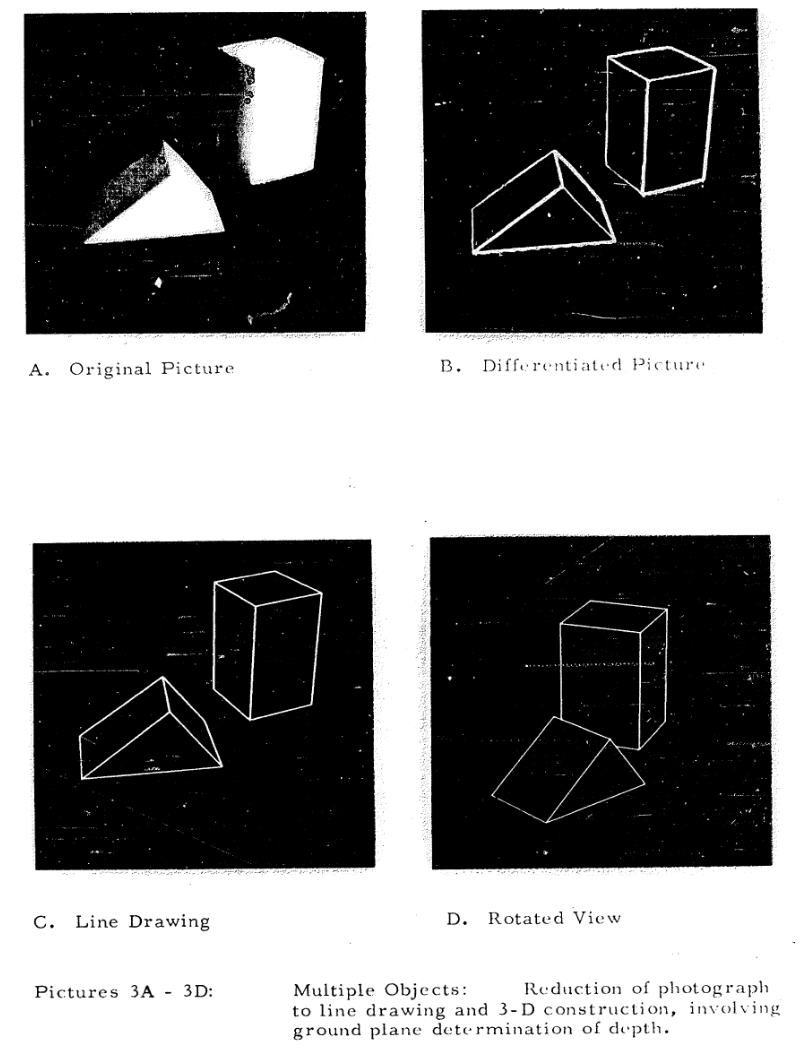

Many of the subfields of Machine Learning (the subfield of AI that leads to most media coverage these days), such as Computer Vision or Natural Language Processing, involve attempting to replicate some aspect of human intelligence. Since it has turned out that replicating human-level intelligence is incredibly difficult, AI researchers have for decades been tackling these tasks in an incremental approach, by defining ever more ambitious tasks relating to human intelligence to address. For example, in the earliest days of computer vision one task was converting 2D images of 3D shapes to a programmatic representation of these 3D shapes that could be rotated and manipulated with a computer:

This is a useful task to solve, but it would obviously be incorrect to characterize solutions to it as being able to, for instance, create a programmatic representation of any object from a 2D image as opposed to just simple 3D shapes. The same broad point applies to today’s AI developments: though the broad problem being addressed may be something as straightforward as “text summarization”, the details of the solution matter – how long can the text being summarized be? Is the solution only good for one kind of text? Does it maintain the factual content of the text being summarized? And so on – the details really matter. As responders to our survey said:

Be very, very specific about the problem that’s being solved for. eh “can write a novel” vs “can write two coherent sentences in a row” vs “can write a factually true news articles”

“Superhuman performance” should be explained carefully i.e. on what metric and what human? How narrow is the task? How much data/compute did the model use?”

AI researchers and authors Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis also emphasize this point in “Six questions to ask yourself when reading about AI”:

“So whenever you hear about a supposed success in AI, here’s a list of six questions you should ask:

“1. Stripping away the rhetoric, what did the AI system actually do here? (Does a “reading system” really read, or does it just highlight relevant bits of text?)”

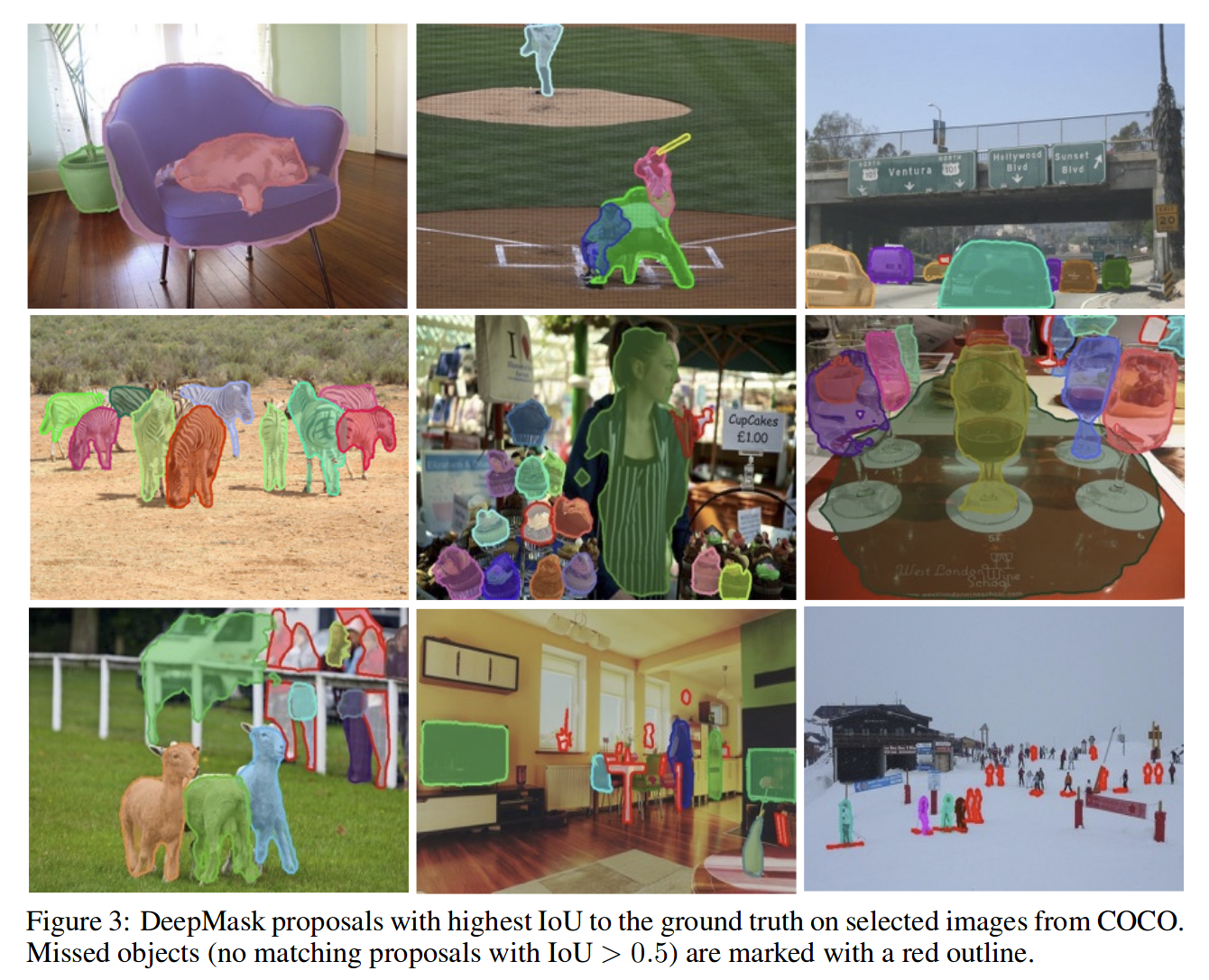

With regards to demonstrations of Machine Learning algorithms, one concrete action to take besides just correctly describing the precise details of the task is to also provide examples from the dataset the algorithm is trained on and outputs it provides for various inputs. This is very often done in Machine Learning papers, precisely to get across an idea of the type of inputs the trained program can work for and its qualitative performance:

Good AI journalism: ask probing questions about the data used for training to help others understand potential weaknesses of the model outputs.

— L Quera (@Surreabral) August 17, 2019

Problem to be avoided: accepting accuracy/quality metrics without enough info on training inputs or test sets.

Do: call out limitations

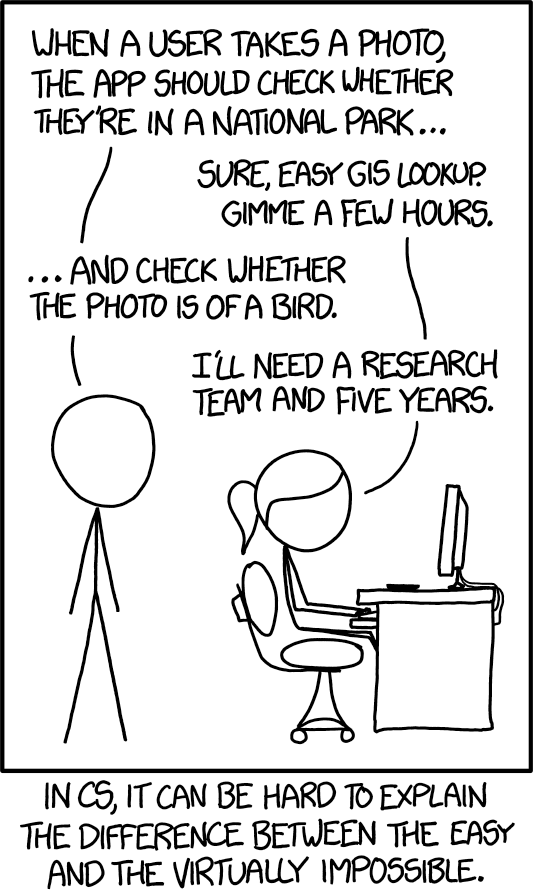

A corollary to being clear about what the task is, is being clear about what it is not. The difficulty of solving related tasks in Computer Science may not be apparent to those without experience with it, as conveyed well in this XKCD comic:

So, it may not be obvious to readers that a program that can play Go, such as AlphaGo, cannot also play Chess, or do anything else. So, specify what the problem is, as well as what it is not, as once again conveyed by Julian Togelius in his blog post:

Recommendation: Don’t use the term “an AI” or “an artificial intelligence”. Always ask what the limitations of a system is. Ask if it really is the same neural network that can play both Space Invaders and Montezuma’s Revenge (hint: it isn’t).

“Six questions to ask yourself when reading about AI” also suggests several relevant questions to this point:

“2. How general is the result? (For example, does an alleged reading task measure all aspects of reading, or just a tiny slice of it? If it was trained on fiction, can it read the news?)”

…

“6. How robust is the system? Could it work just as well with other data sets, without massive amounts of retraining? (For example, would a driverless car system that was trained during the day be able to drive at night, or in the snow, or if there was a detour sign not listed on its map?)”

Don’t: ignore the failures

Even for narrow tasks, AI systems invariably don’t have perfect performance. It is important to point this out, but also to be careful about how these errors are justified; portraying these failures as unpredictable or mysterious may further the impression of agency on the part of the system, giving readers the wrong idea. Rather, failures are due to a not-yet understood behavior of a complex system, and it’s caused by humans who failed to design a sufficiently robust system, used flawed data, or otherwise lead to the system’s failure. Acknowledging the decisions of people (AI engineers) and how that shapes the system a lot (it’s not just decisions made by “the AI”) is important for accurately portraying how AI is used today. As stated in response to our survey:

“Understand how problems/patterns in the data can affect the system, and that datasets are usually too small / incomplete / not exactly what you need for the task, and this is what causes a lot of shortcomings”

Do: present advancements in context

A worrying pattern we’ve seen with coverage of new AI results is presenting them and their implications as if they are the first of their kind. For instance, when Google presented new work on making out who is speaking in a crowded room, many articles pointed out that this was “spooky” while failing to mention the result was an incremental advance on decades of research on the problem. While it is useful to cover new ideas and their implications, presenting them like this may lead to more concern than is warranted. Again, quoting Togelius:

Keep in mind: AI is an old field, and few ideas are truly new. The current, awesome but a tad over-hyped, advances in deep learning have their roots in neural network research from the 1980s and 1990s, and that research in turn was based on ideas and experiments from all the way back in the 1940s. In many cases, cutting edge research consists of minor variations and improvements on methods that were devised before the researchers doing these advances were born. Backpropagation, the algorithm powering most of today’s deep learning, is several decades old and was invented independently by multiple individuals. … Recommendations: When writing stories about exciting new developments, also consult an AI researcher that is old, or at least middle aged. Someone who was doing AI research before it was cool, or perhaps even before it was uncool, and so has seen a full cycle of AI hype. Chances are that person can tell you about which old idea this new advance is a (slight?) improvement on.

A related point is to avoid vague statements such as “techniques like this may soon enable home robots,” which obscure rather than clarify the implications of new research. The same holds for concerns related to research; covering possible present day misuses is preferable to warnings of vague future consequences. In general, any new paper will present a small amount of progress towards the grand challenges of AI, and this should be presented clearly.

Conclusion

We hope this set of recommended best practices presents some non obvious pitfalls when it comes to reporting on AI. Of course, suggestions that apply to coverage of any topic (talking to a variety of sources, being skeptical of the perspectives of those with a financial stake in the topic, avoid clickbait, etc.) also apply to AI, and AI researchers are often annoyed to find them not being followed:

2. clickbait titles/pictures: they are probably the fastest way to get traffic but fast doesn’t mean good. Concise and descriptive > catchy and inaccurate. Be a responsible journalist/blogger/presenter, even if it costs you getting less attention in short run.

— Amir Zamir (@zamir_ar) August 18, 2019

As AI researchers we are understandably very invested in the topic, and we wish it to be communicated to the public as accurately as possible. We hope this article can help with that, and we encourage any journalists with ideas on how we can further help to reach out to us.

Thank you to Abigail See and Jacky Liang for help editing this, and to many others for contributing their thoughts.