Evil Software Du Jour: Google's Cocktail Party Algorithm

Recent privacy concerns over work from Google showcased how easy it is for media to immediately jump to unlikely worst-case outcomes

Last month’s coverage of speech-processing research from Google revealed a trend of excessive caution paid to innocuous tech developments.

What Happened

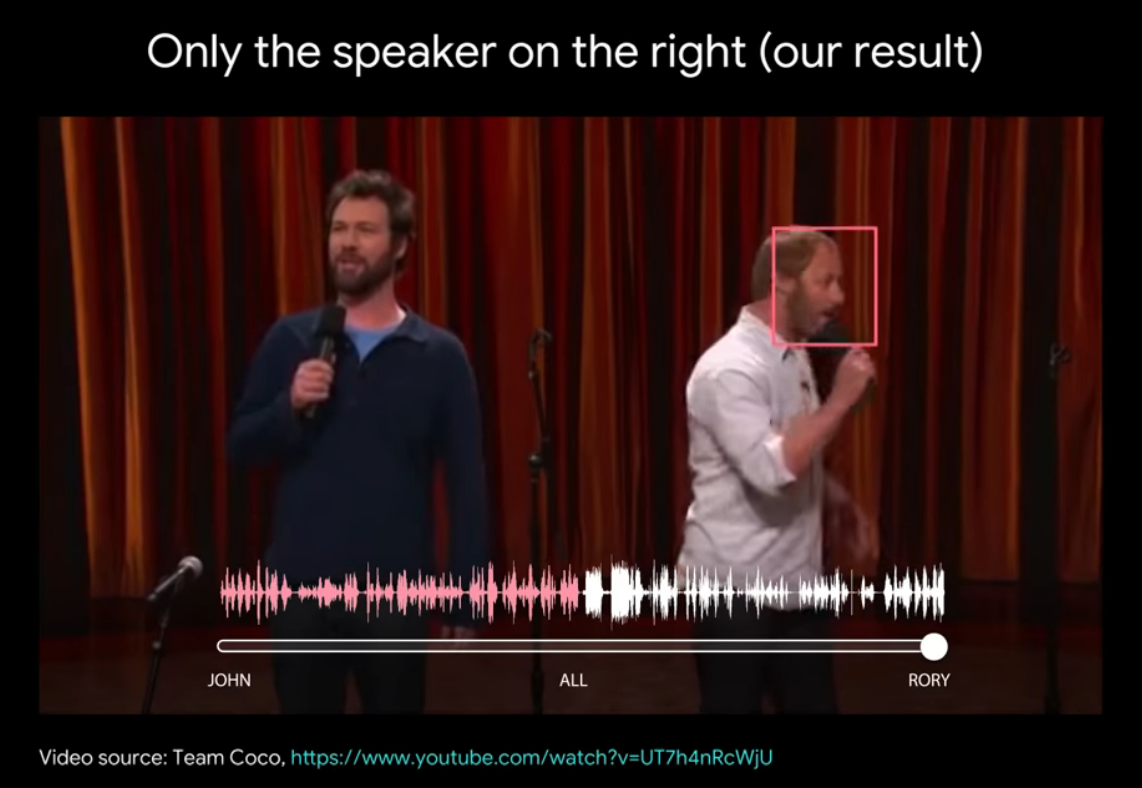

In April, Google AI researchers introduced a new method for processing a video clip of two people talking over each other to produce a text transcript of what was said by each person. Prior work in the field of automatic speech recognition has focused on consuming spoken audio signals or video input of speakers’ mouths to produce a transcript of what was spoken. Google’s approach combines both audio and video to not only to isolate speech signals from multiple simultaneous speakers but also to attribute each speech signal to its speaker. The authors titled their work “Looking to Listen at the Cocktail Party” in reference to the cocktail party effect – the human ability to selectively listen to just one voice while filtering out many other simultaneous sound sources.

The authors offer closed captioning as an example of the applicability of the tech and conclude by stating that they are “exploring opportunities for incorporating it into various Google products.”

The Reactions

Ars Technica quickly construed Google’s new technique as a Big Brother-esque surveillance tool in an article titled “Google works out a fascinating, slightly scary way for AI to isolate voices in a crowd”

The privacy ramifications of this kind of tech seem just as obvious as the potential use cases. Google’s voice isolation is far from bulletproof in the examples above, but with some more fine-tuning, it could make for a powerful eavesdropping and surveillance tool in the wrong hands.

Ars wasn’t the only publication to imply that readers should be frightened of this development:

The privacy implications of something like this are honestly pretty serious. If performance can be improved, a system like this could even be able to pick a single voice out from a crowd on the street.

Imagine the technology advancing enough to the point where it’s able to pinpoint a specific voice from a bustling street in an urban city such as New York? Combined with security cameras, Google’s new tech serves yet another fuel for panic over security.

[Google’s speech separation] does sound spooky, considering how much of Google’s technology is already used by military and intelligence for surveillance.

The coverage is formulaic: each publication offers a basic explanation of what this technology is and how it could be used, followed by a discretionary footnote about privacy ramifications.

Our Perspective

In 1983, Sony’s Betamovie gave the average consumer the ability to capture their lives in stunning Betamax with autofocus. And of course, 35 years later, most Americans own a pocket-sized device that can do all this and more.

So, when compared to simply watching recorded videos, how might this method enable novel, enhanced surveillance?

Understanding Speech

One way bad actors may have gained new tools to surveil others is if this method is better than humans at understanding speech in a recorded video.

For humans, speech recognition (understanding spoken words from audio alone) is usually easy, while lipreading (understanding spoken words from just seeing but not hearing the speaker) is very difficult. What’s important to note, however, is that the kind of lipreading that usually comes to mind isn’t what this new technique is doing. The authors of the paper suggest in the first sentence of their introduction that this is very much an effort to emulate a skill that humans already have:

Humans are remarkably capable of focusing their auditory attention on a single sound source within a noisy environment, while deemphasizing (“muting”) all other voices and sounds.

Crucially, the authors then suggest that humans are considerably better at recognizing speech when they can see the speaker’s face. The bottom line emerges: this new technology is an effort to make machines able to do something humans can do by recreating the conditions that humans require to do it the most effectively. And though the results are impressive, the tech is nowhere near humans’ prowess at this task.

How Novel Is this, Really?

Even if the technology isn’t a drastic improvement over humans’ ability to understand speech from video, we may still be concerned about automation. Could this technology be used to automatically parse large volumes of recorded video for sensitive information?

While it’s true that automation enables that kind of processing, this is far from the first-ever automatic speech processing method.

Early automatic speech recognition has existed since the 1960’s, and speech separation approaches have been proposed and implemented with varying degrees of success over the past two decades (2004, 2007, 2011, 2014). And in 2016, researchers at The University of Oxford achieved “sentence-level” lipreading: lip reading that can contextualize and predict whole sentences just from video, far surpassing prior work that could only recognize individual words.

This isn’t even the first method for automatic speech recognition using combined video and audio inputs, either. In 2007, IEEE published a study whose authors purported to achieve significantly better speech recognition than with audio alone by adding video signals to their processing. They make no promise of separating overlapping speech signals, but the work shows that similar systems, with similar use-cases, existed before Google’s.

The authors do note their algorithm is quantitatively superior to this prior work, but how significant is that improvement? It’s hard to say, but a likely guess is that the transcripts produced by prior methods would not be significantly less clear than those produced by this method. It’s actually pretty difficult to cook up a use case specific to Google’s speech separation that wasn’t possible prior to its creation. It would probably involve mass-processing on a large volume of video recordings against a database of human faces.

But now we’re just describing the computer scene from Minority Report.

And What About Alexa?

It is also important to note that all the above is not ready to be used as an off-the-shelf spying tool; it’s research, and so only really usable by AI experts. Meanwhile, high-quality speech recognition products that could be used to spy on all of us are being bought by the millions every year: Alexa and Google Home, to name a couple. As these commercial products demonstrate, precise speech recognition is achievable with audio signals alone; video is just the ‘cherry on top.’ In fact, the authors’ own paper shows this as well:

And as if that’s not enough, there is free open source software that could be used by any programmer with no expertise in AI to transcribe speech from audio recorded with any microphone whatsoever. And if that’s not enough, there are even tutorials online on how to combine that software with some hackable mini computers and cheap ‘microphone arrays’ (the key technology enabling Alexa’s and Google Home’s reliable speech recognition) to create one’s very own Google Home spy machine:

So… if one were to spy on people with AI, this latest development from Google hardly seems like the tool they would go with first. After all, it’s just research - why use it when there is already commercialized, production-quality technology available?

But What If…?

Android Police and Tech Times additionally specify a hypothetical surveillance use-case that is contingent on further improvements to the tech: if significantly improved, could this tech pick out the speech of unwary targets from a distance?

Well, without a strictly defined limitation on time or resources, the answer is probably yes. At that point, however, the discussion has shifted from an analysis of the threats posed by this technology to a rejection of all developments in speech processing.

A Note On Media Accountability

As each article hedged on the fear that this technology could be used for surveillance, the lasting impression of the coverage was that the technology is a privacy threat.

At the end of the day, this is just AI research. Though some research is legitimately worrying, it is not always intrinsically scary nor can it always be assumed to benefit those with nefarious intentions the most. As tech reporting becomes saturated with articles that predict scary outcomes from innocuous developments, it becomes more and more difficult for readers to know or care about what kinds of developments are actually threatening - “the boy who cried wolf, AI edition”. Reporters must learn to differentiate between legitimately worrying technology and simple tools that can be misused, and always contextualize new research with what has come before it.

TLDR

Google AI’s development is a relatively minor contribution to the tapestry of speech recognition research, not a privacy-shattering new concept. If we were to concoct a hypothetical situation in which Google’s technology offers a significantly greater threat than previous methods, that situation would need to involve:

- Video recording without consent

- Multiple concurrent speech signals

- Unobstructed view of the speaker’s mouth

- A large volume of data meeting all of the above criteria

There are plenty of existing technologies that let people spy on each other. In-home assistants like Google Home and Alexa can even be modified explicitly for surveillance purposes – no video signal required. This speech separation method, meanwhile, is unlikely to threaten anyone’s privacy.