AI Strategies of U.S., China, and Canada in Global Governance, Fairness, and Safety

Constructing a set of three evaluative criteria for national AI strategy, and using them to consider US, Chinese, and Canadian policy

With a number of developed countries prioritizing research and development in AI, both these nations and AI research institutes are focusing on whether these policies are indeed well-considered. There is plenty of information both covering and generally evaluating the AI policies of different nations, such as the US and China. In this editorial, we add to this conversation by evaluating national AI strategies against a clear set of recommendations. In particular, we will look at a few AI policy recommendations from groups like the Future of Humanity Institute (FHI), and use these guidelines to evaluate different national AI policies.

The FHI and similar groups, such as MIRI and AI safety groups within DeepMind and OpenAI are primarily focused on mitigating existential risk, particularly in regard to advanced AI. Many of these groups have access to excellent technical researchers, and they therefore boast a strong understanding of the potential problems we may encounter as AI continues to develop. We believe that these recommendations, which span topics much wider than those in R&D, can be used to develop a coherent and useful common framework with which to evaluate different national strategies. This comprehensive evaluation will allow us to understand the broad consequences of these policies and give well-considered recommendations on potential changes. At the same time, in order to be useful the evaluation needs to be specific and concrete enough to have actionable recommendations, so we hone in on three areas of focus:

- Given the potential for AI to have transformative effects on many sectors of society, it is vitally important to ensure that research and development of AI technology is both safe and regulated enough to avoid catastrophic consequences.

- Further, the potential for AI systems to amplify already existing assumptions and biases that have proven to be problematic should also be taken into account–we should do our best to make sure that the use of these systems respects fairness, ethics, and human rights. In particular, the FHI points out that “AI has the potential to have profound social justice implications if it enables divergent access, disparate systemic impacts, or the exasperation of discrimination and inequalities” (FHI).

- Lastly, the potential for AI development to create competitiveness and race conditions also needs to be considered in national strategies. That is to say, while healthy competitiveness can indeed aid the development of AI, countries should be careful to avoid allowing this to run the risk of arms races and speedy development that pays no attention to the impacts of developing AI.

In this article, we evaluate the national strategies of the United States, China, and Canada along these three lines. We’ll look at more countries in the future, but a great deal of media attention has been foisted upon the US and China in particular (such as with Kai Fu Lee’s book AI Superpowers), and Canada boasts some of the most important contributions to AI research in recent history. First, we’ll provide descriptions of the three criteria. Then, we’ll go on to describe each country’s policy and evaluate how well we believe it fulfills each criterion. In particular, we think the recent US AI bill presents some promising strategies for developing safe and effective AI, while China’s government-pushed strategy seems optimized for massive growth in the AI sector, but it appears to have less concrete work towards risk mitigation. We believe that among the three, Canada’s policies on AI may present a particularly good model for countries hoping to develop both safe and effective AI.

Criteria

1. Global Governance - Nations should cooperate on the development and the standardization of AI.

The first criterion, and arguably the most important because it will likely have the potential to impact all the others, states that global governance–i.e. internationally recognized, overseen, and agreed upon standards followed by all nations in AI development–and international cooperation is vital to guide the safe and beneficial development of AI while avoiding unwanted situations like race conditions and security threats. Dangerous race conditions indicate situations where otherwise healthy competition to develop systems like AI may result in unforeseen and unwanted goals, such as the development of AI-powered weapons in both military and cyber contexts.

2. Fairness - AI should be developed and deployed in a way that minimizes bias and benefits everyone.

The second criterion recommends that groups engaged in the development of AI pay attention to how AI applications can amplify existing biases, such as those based on race, gender, and ability. AI bias research and mitigation should go beyond purely technical approaches and draw upon different disciplines, such as philosophy and psychology. Further, information about participation of different groups, especially marginalized ones, within AI R&D should be made open, and genuinely inclusive workplaces should become a sought-after goal. Finally, strong accountability and oversight mechanisms should be put into place along with ethical codes for steering the AI field.

3. Safety - AI systems should only be used if they have well-understood and accepted risks and safety guarantees.

The final criterion centers on questions of AI safety–in particular, we find it important to evaluate how much priority and research national strategies allot to problems like misaligned values between AI and humans that can cause AI to pose a threat to individuals and institutions. Important questions to be considered include whether AI systems are given enough time to be tested for safety and unintended consequences, whether value alignment is considered, and how much priority national strategies give to safety and controllability of AI systems.

Evaluation

United States

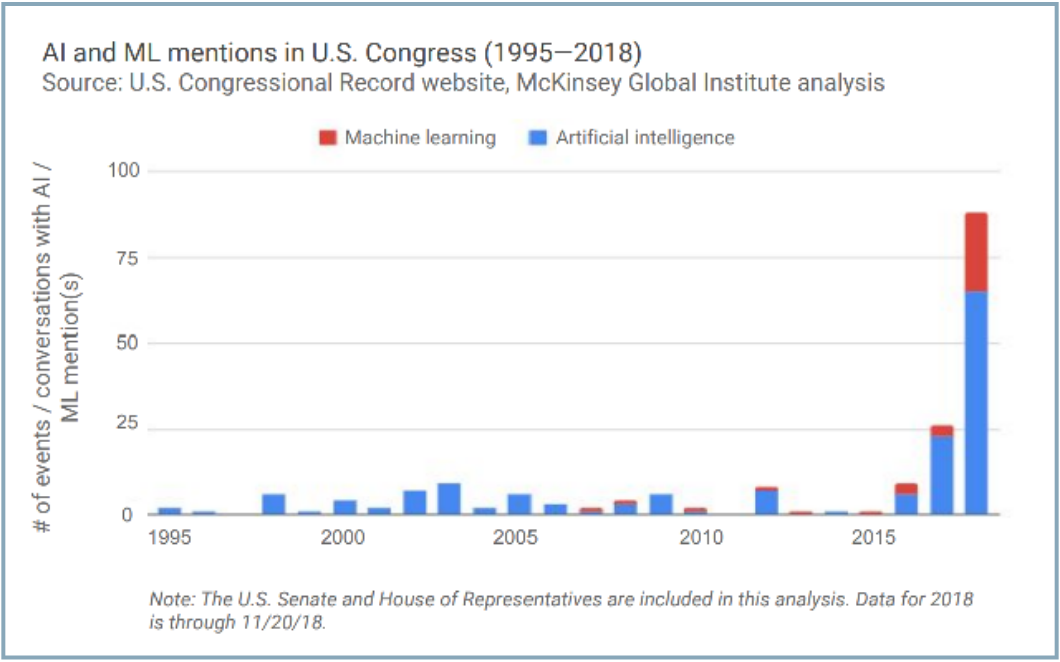

While the Obama administration produced a document on AI policy towards the end of his tenure, the Trump administration released its own Executive Order on maintaining American leadership in Artificial Intelligence. Trump’s order does seem to take these three criteria into account, but as we will see, some subtle issues do remain. The Executive Order calls on officials in charge of management, budget, economics, and domestic policy, to issue a memorandum that will inform regulatory and non-regulatory approaches, i.e. policies more focused on development than risk mitigation, regarding AI. It also asks officials to consider ways to reduce barriers and promote the use of AI technologies while “protecting civil liberties, privacy, American values, and United States economic and national security.” While the Executive Order isn’t law, it sets out clear deadlines for a few of the actions contained within, and it is the clearest statement the White House has made on AI. In addition, a recent bipartisan AI investment bill includes a number of components that would help the US in developing effective and accountable AI. Besides $22 billion for investment in research, the bill calls for the development of standards to evaluate AI algorithms, as well as significant efforts for public education on both the technical and societal aspects of AI.

With regard to the first criterion, the recent AI bill manifests an improvement over the earlier Executive Order, but it appears to fall short in some aspects. In Trump’s Executive Order, security rhetoric such as “protecting our critical AI technologies from acquisition by strategic competitors and adversarial nations” may prove troubling in regards to AI governance and race conditions. If nations preempt threats in AI development and view each other as competitors and adversaries, existing risks of conflict from such discourse may be amplified further by the presence of AI systems. In line with the administration’s agenda, America-centric rhetoric pervades the Executive Order. While the new bill calls for increasing investment in AI research, development, and education, it contains only a small number of statements with regard to global cooperation. It calls for the evaluation of international opportunities w/r/t/ AI R&D and the coordination of engagement with international standards bodies to “ensure United States leadership in the development of global technical standards.” However, it is likely that global governance and standards will have to go beyond purely technical considerations to sufficiently oversee and mitigate AI risks.

Given how outspoken US researchers and firms have been on issues of fairness and bias in technology more generally, it is unsurprising that the US plan scores well on the second criterion of addressing AI bias and fairness. In particular, the recent Senate Bill stresses that special effort should be made to draw contributions in AI from underrepresented communities. The Bill advocates “identifying and minimizing inappropriate bias in data sets, algorithms, and other aspects of artificial intelligence” and says it will assure that R&D and applications efforts with regard to AI will “create measurable benefits for all individuals in the United States, including members of disadvantaged and underrepresented groups” (Senate Bill). Further, the Bill supports the creation of an interagency committee, involving the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, NASA, the Department of Defense, and the National Institute of Health, among others. With these commitments in hand as well as one of creating multi-disciplinary centers for AI research and education, the US government appears well-poised to both adopt a multi-disciplinary approach to AI research and development and foster inclusion in both the creation and impact of AI.

With respect to the third criterion, even if there were little consideration from the government, the presence of groups such as MIRI and OpenAI in the United States means that there is enough interest among prominent AI researchers in safety problems, and this will likely require the government to consider these problems seriously should it hope to cooperate effectively with AI researchers. Fortunately, politicians do appear to be on board–the Senate Bill’s mandates include “supporting efforts to create metrics to assess safety, security, and reliability of applications of science and technology with respect to artificial intelligence” (Senate Bill). The Bill also specifies that meetings of US officials on the topic of AI should include the topics of algorithm accountability, explainability, and trustworthiness–these are listed as educational priorities along with societal and ethical implications for the use of AI and other related topics.

China

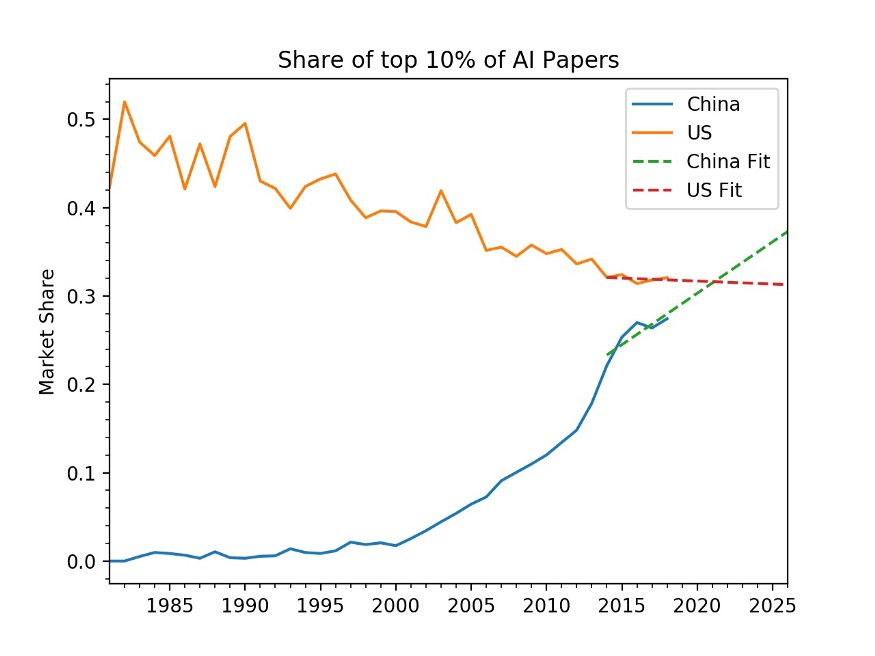

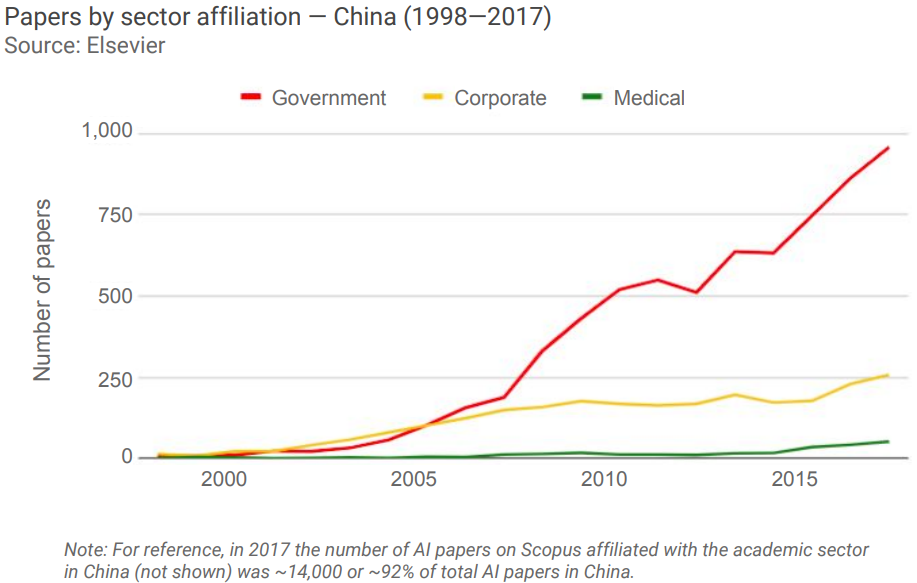

China has laid out their AI strategy In a remarkably different format from the US’s, in a lengthy development plan (AIDP). Of note in their strategies are goals to construct a first-mover advantage, utilize the particular advantages of socialism to consolidate resources for the oversight of AI development, accelerate commercialization of AI for the purpose of market dominance while keeping the government involved in R&D oversight, and advocate for open-source development. As detailed in VC Kai-Fu Lee’s work AI Superpowers, China’s government has already propelled the country’s development in AI R&D by encouraging AI research through both funding and increasing manpower by attracting talent (i.e. Baidu’s hiring of Qi Lu from Microsoft), promoting education in AI, and shifting existing industry forces in tech towards AI. Further, intentional lack of regulation on data use allows apps like WeChat, China’s “everything” app used for everything from texting to payments, to collect far more data on consumers and citizens than apps from many other countries are able to – any and all of this information is then shared with the government in Beijing. There has been a recent push towards consumer data protection, but the massive amount of data and increased surveillance have already done their job in helping provide plenty of data for AI to be integrated into daily consumer life . Further, even a data protection regime in China will not “undermine the government’s ability to maintain control” even in its quest to gain consumer trust (Slate). This government-supported push towards AI R&D, coupled with China’s lack of data regulations and unique startup culture that cares less for Intellectual Property, has allowed it to make great strides in finding ways to apply AI to daily life. Kai Fu Lee drives home the point about IP well: “Chinese companies are first and foremost market-driven… It doesn’t matter where an idea came from or who came up with it. All that matters is whether you can execute it and make financial profit” (Lee). As a result, lack of enforcement on IP has been conducive to companies attempting to find ways to exploit and improve upon each others’ technology. When it comes to finding ways to apply AI for purposes like consumer goods, this model has a great number of benefits because companies are forced to compete in making their AI-powered products high-performance and competitively priced.

While China’s plans and statements boast an interest in taking leadership on global governance for AI, they lack specificity and detailed ideas for implementation that will be important should China actually take a central role in such matters. The AIDP expresses strong interest in concentrating top AI talent and research in China, using the government’s involvement somewhat differently from the other countries. However, its sentiment and current implementation involve aggressive expansion of military use of AI. This has indeed been practiced in “collaborations between defense and academic institutions in China,” and in particular a lab launched by Tsinghua University aims to create “a platform for the dual-use of emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence” (Future of Life). The recent Beijing AI Principles (BAIP) published by prominent Chinese AI researchers (not the government) do appear to represent a step in the right direction, discussing guidelines for proper, safe, and equitable AI development in regard to R&D, use, and governance. While many of the principles are agreeable with taglines such as “Do Good”, “Be Responsible”, and “Be Ethical”, the BAIP has received criticism for its lack of doing “enough to address actual real world development and use cases” (TechNode). Indeed, many of the statements in the document are quite general, such as the first which states that AI should be developed to “benefit all humankind and the environment” and that “[h]uman privacy, dignity, freedom, autonomy, and rights should be sufficiently respected.” While the publication of BAIP is significant, it does little in the way of making specific policy suggestions and concrete plans for how the principles would be observed. This is pertinent because the principles are not in themselves anything groundbreaking–most other countries and AI researchers around the world would agree with the principles laid out in the BAIP, and it follows a long list of declarations on AI principles from other influential organizations (see DeepMind, OpenAI, the UK’s House of Lords, Google, and the OECD).

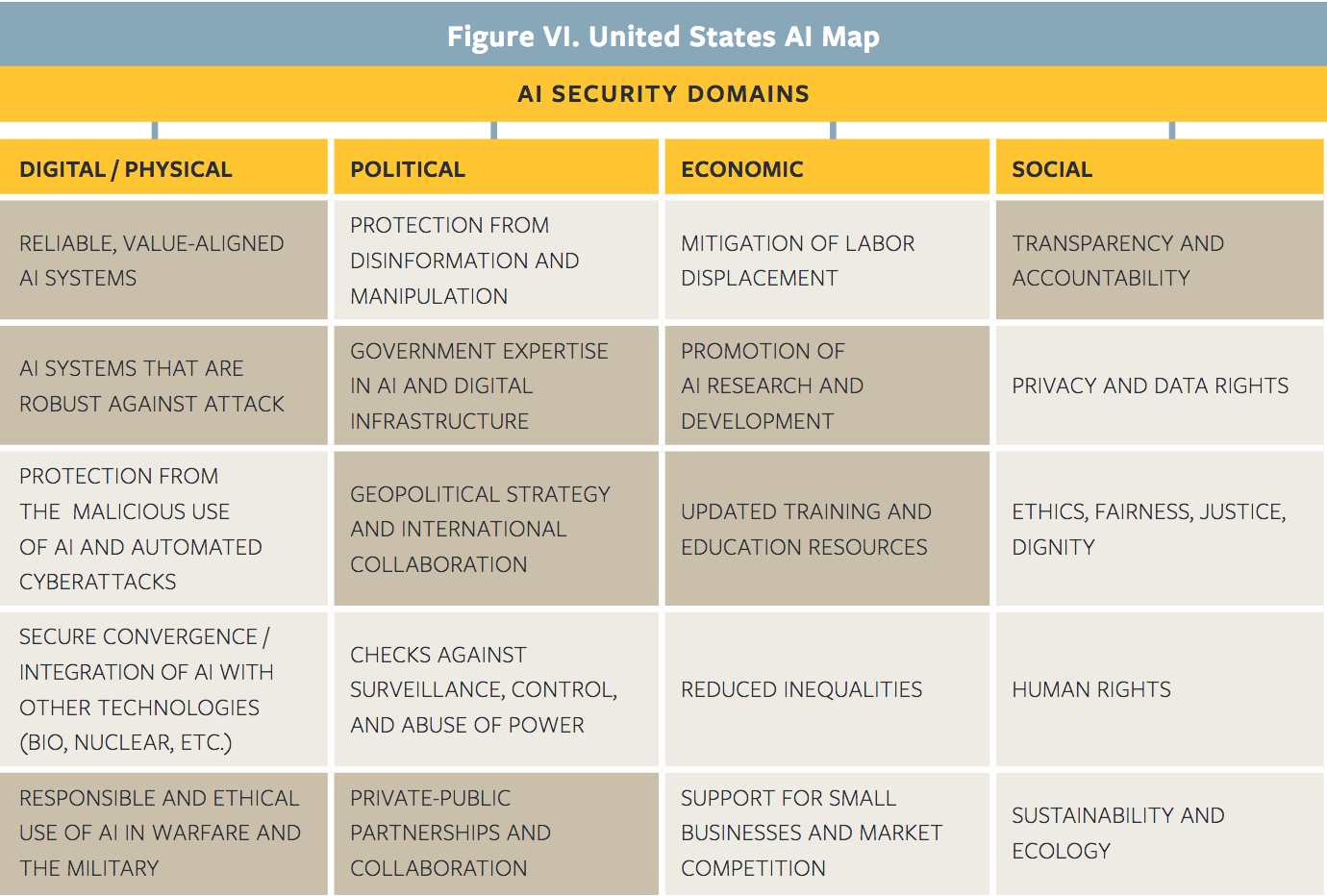

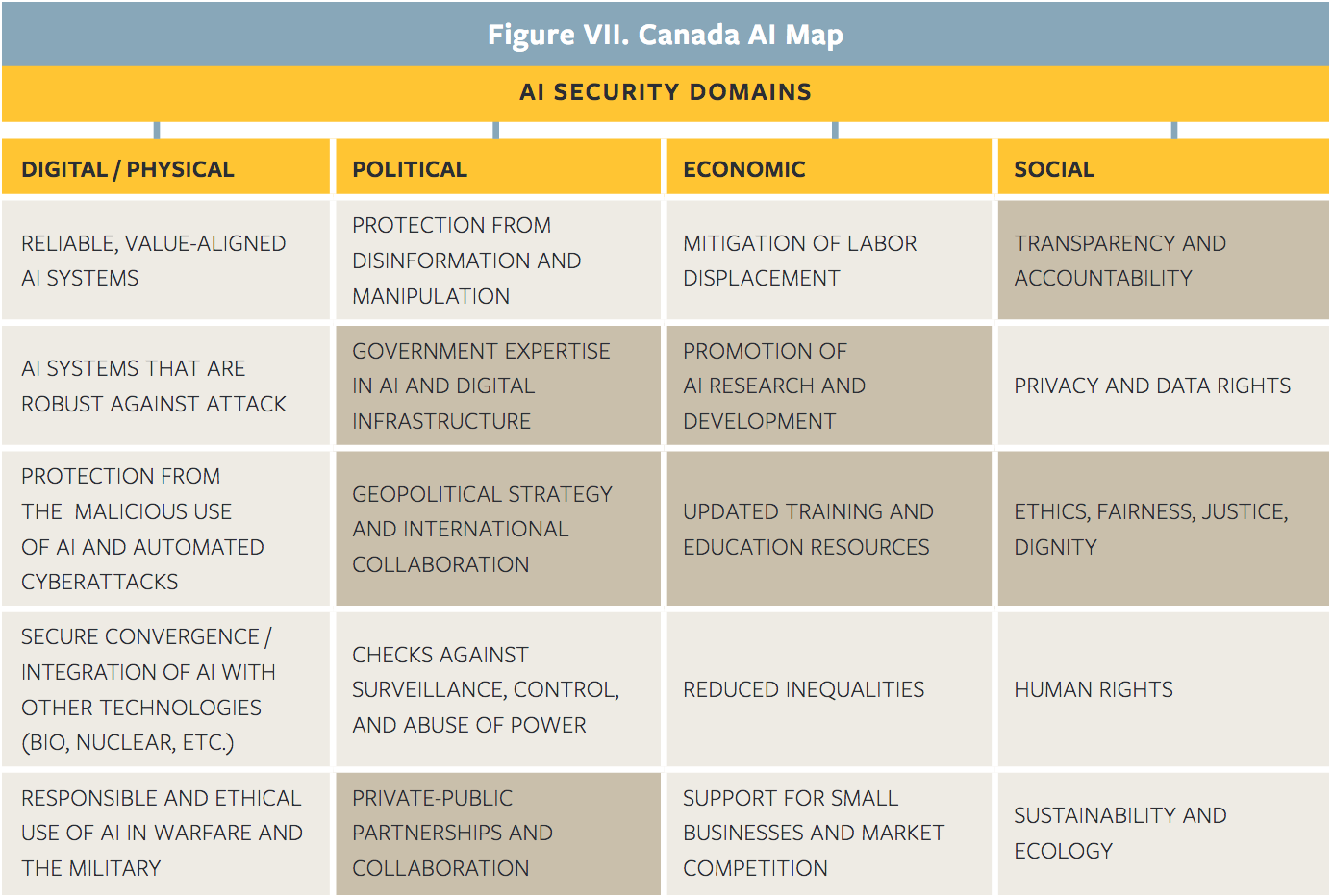

While the BAIP makes the point that addressing AI bias and fairness is important, China does not have much in the way of concrete policies in this area, suggesting there isn’t much emphasis on bias and fairness issues. Beyond information itself, having as much diversity in representation both in creating and evaluating AI systems will be important in mitigating potential bias. China’s lack of focus here is also noted in The Center for Long-term Cybersecurity’s (CLTC’s) paper that identifies sixteen topics falling under AI security domains (i.e. digital/physical, political, economic, and social) and identifies where different countries place policy priorities among the sixteen options. It is of note that areas that are not a focus for China include “checks against surveillance, control and abuse of power”, “reduced inequalities”, “human rights”, and “protection from disinformation and manipulation”. Further, while China’s interests and thoughts as expressed in the AIDP and BAIP have a component of wanting to “do good” with AI in them, there is a large gap between the sentiment and taking concrete action towards mitigating abusive and manipulative uses of AI systems.

AI safety and security issues indeed appear to be on Beijing’s radar, but their current approach to standards-setting in this area may pose some issues as a result of an aggressively inserting their voice and only taking input from a homogeneous set of actors on national AI policy. While there don’t appear to be detailed policy guidelines on AI safety and security from the Chinese government, a major government-affiliated think tank released an expansive white paper on AI and security last year that “offers a multidimensional assessment of security and safety risks and potential ways to respond to them related to AI” (New America). The AIDP and the BAIP show how issues about AI safety, security, and ethics have gained traction in the Chinese AI research community. One article notes that given the potential for Chinese-developed AI algorithms to “have effects on users outside of China, China’s government aims to advance global efforts to set standards around ethical and social issues related to AI algorithm development” (New America). It also points out how China’s drive to help set AI standards has some motivation in economic gains, commercial competitiveness, and the international prestige of “having a seat at the table” in settings such as global governance and the creation of international AI standards. While this attention is indeed a positive step for China, major civil society groups of the kind that are well-represented in discussions in the US and Canada (such as ordinances that allow for civic oversight when AI-based systems are deployed (Open Global Rights)) are unfortunately absent from the table in leadership and participation in discussions around AI safety and standards in China. Rather, private sector actors appear to be dominating the conversation. While China is indeed recognizing the need for standards and safety, there is some worry that “China’s assertive approach to standards-setting will result in technological lock-in and stifle competition” (New America).

Canada

Canada’s Pan-Canadian AI Strategy makes a commitment to work in partnership with three newly-established AI institutes–the Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute, Mila, and the Vector Institute– to achieve four main goals:

- To increase the number of AI researchers and graduates

- To interconnect the three new AI institutes

- To develop global thought leadership on economic, legal, policy, and ethical implications of AI advances

- To support a national AI research community.

While Canada’s AI strategy boasts less specific plans than the other two countries’, it does have a strong sense of purpose and strongly support cooperation between government and AI researchers.

Separately from its general strategy focused on Canada’s leadership in AI R&D, Canada has paid attention to the social impacts of AI systems which have the potential to make society-influencing decisions and greatly impact the lives of many people. Canada’s University of Montreal has put forth a document detailing principles for the responsible use of AI called the Montreal Declaration, “forged on the basis of vast consensus” of public opinions and jointly created by philosophers, sociologists, jurists, and AI researchers (The Conversation). Of the ten principles laid out, those of note in our evaluation are the principles of well-being, respect for autonomy, protection of privacy and intimacy, democratic participation, equity, diversity and inclusion, and prudence. The Declaration represents a commitment by Canada to proactively manage the societal impact of AI, and Canada’s new Advisory Council on Artificial Intelligence, created by the Canadian government and composed of leading researchers, academics, and business executives, represents a concrete step towards this. The council will not autonomously make policy decisions and does not have the purview to fund academic research, but it advises the Canadian government on building Canada’s strength in AI and promoting economic growth while also “promoting a human-centric approach to AI, grounded in human rights, transparency, and openness… [to] increase trust and accountability in AI while protecting [their] democratic values, processes, and institutions” (Newswire). Since no council members are Canadian politicians, the council’s opinions will be independent of the government’s views and policies. The group will not operate quite like a think tank, but reflect on various topics pertinent to AI policy in a series of meetings.

Should Canada’s plans for AI development be followed, its efforts will likely be the most successful on the fronts of global governance and conflict avoidance. While Canada does have an interest in becoming a leader in AI, its aspirations are couched in non-confrontational language like “enhance Canada’s international profile” and pursue “socioeconomic benefits for Canada.” This sheds some light on Canada’s views with regard to international competition in AI and may signal that Canada does not view AI leadership and status as a zero-sum game. Canada’s expected results also includes “increas[ing] collaboration across geographic areas of excellence in AI research.” Further, Canada and France’s recent announcement of an International Panel on AI demonstrates concrete commitment to global cooperation on AI efforts.

In its own effort to lead the way, Canada has made concrete progress towards considerations of mitigating bias in AI and promoting fairness and ethics. The nation has already hosted a joint symposium with the UK on Ethics in AI. The symposium’s workshops focused not only on ideas and concepts about ethics, but discussed concrete topics such as existing solutions for mitigating problems, challenges to implementing ethical AI in practice, and ethical AI best-practices. Further, Canada’s Advisory Council on AI is chaired by outspoken proponents of ethical practices in developing AI. An article from Borealis AI, whose Head is a co-chair of the committee, outlines six concrete steps towards confronting bias in AI and includes actual measures that have already taken, such as the AI for Good Summer Lab which seeks to diversify the industry by providing seven weeks of training for undergraduate women in AI.

While Canada appears to do well on our other two criteria, the national strategy unfortunately does not address AI safety very much head-on. This does not indicate any negative intentions on Canada’s part, but rather that Canada’s AI policy priorities simply lie elsewhere. The CLTC’s paper notes that while Canada’s policy covers the political, economic, and social dimensions, it does not include considerations such as reliable and value-aligned AI systems, AI systems that are robust against attack, and protection from malicious use. However, given the array of strong proponents of research in Canada and the high probability that it will pay attention to standards and ideas coming from the global AI community, there is little doubt that should Canada choose to participate in AI safety efforts, it will do far more good than harm.

Conclusion

While each of the three countries we have considered have very different approaches to AI in both R&D and governance/standards efforts, each does possess its own strengths. The US’s and China’s national strategies address a wide range of topics with different approaches. While Canada’s focus is a bit narrower than the other two, it appears to be doing an exceptional job of promoting policies and forward-looking plans that will likely help in efforts to mitigate potential negative impacts of the forward push in AI. While no single country’s policy is perfect in any way, we hope that with enough global governance, inclusion of underrepresented groups and nations, and responsible consideration from all types of countries all around the world, we can work towards ensuring that we have a robust plan and policy as new technology continues to impact our daily lives.

Further Reading

Deciphering China’s AI Dream, Jeffrey Ding, March 2018 China’s Current Capabilities, Policies, and Industrial Ecosystem in AI, Jeffrey Ding, U.S. Congress Testimony, June 2019 Technology, Trade, and Military-Civil Fusion, Helen Toner, U.S. Congress Testimony, June 2019