When to Assume Neural Networks Can Solve a Problem

A pragmatic guide to the powers and limits of neural networks

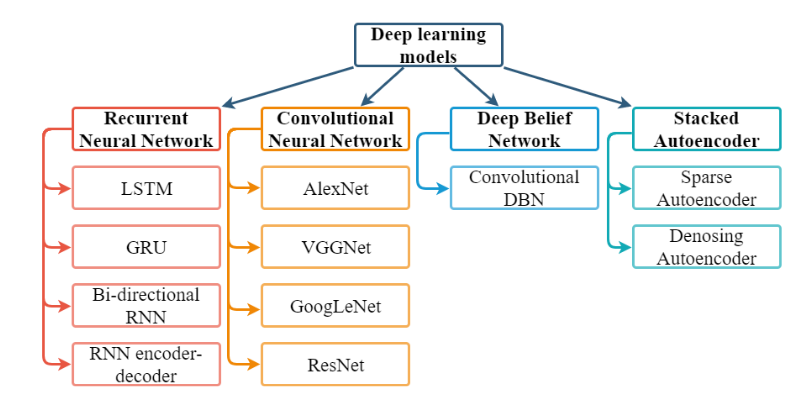

Image credit: Fig 2 in "A Survey on an Emerging Area Deep Learning for Smart City Data" by Chen et al.

This is a revised version of a blog post originally shared by the author on their blog

The question, “What are the problems we should assume can be solved with machine learning?”, or, to be even narrower and more focused on current developments, “What are the problems we should assume a neural network is able to solve?”, is one I haven’t seen addressed much.

There are theoretical frameworks such as PAC learning and AIXI, which at a glance seem to revolve around this, as they pertain to machine learning in general. Unfortunately, if actually applied in practice, these won’t yield any meaningful answers.

However, when someone asks me this question about a specific problem, I can often give a fairly reasonable and confident answer, provided I can take a look at the data.

This piece summarizes the heuristics I use to generate such answers. They are not precise or evidence-based, but I think they might be helpful, and perhaps a good starting point for further discussion on the subject.

1. A neural network can almost certainly solve a problem if another ML algorithm has already been used to solve it

Given a problem that can be solved by an existing ML technique, we can assume that a somewhat generic neural network, if allowed to be significantly larger, can also solve it.

For example, playing chess decently is such a problem that has already been solved. It can be done using small decision trees and a few very simple custom search heuristics (see, for example, here). Thus, we should assume that a fairly generic neural network, using significantly more parameters than the original DT based models, can also successfully tackle this problem.

Indeed, this seems to be the case; one can play chess using a fairly generic fully connected network without requiring any additional built-in heuristics or an architecture specialized for this purpose.

In fact, we can also take any “toy” dataset, such as those on UCI, find the best fitting classical ML model using a library like Sklearn, and train this fairly simple neural network that Sklearn provides. By setting the hidden layer size to be large enough, one will almost certainly match the performance regardless of the model one compares against.

All this being said, this heuristic doesn’t always hold because:

-

a) Depending on the architecture, a neural network could easily be unable to optimize a given problem. For instance, playing chess might be impossible for a convolutional network with a large window and step size, even if the network itself is very large. This shows the importance of choosing an appropriate architecture for the given problem.

-

b) Certain ML techniques have a lot of built-in heuristics that might be hard to learn for a neural network. The existing ML technique mustn’t have any critical heuristics built into it, or at least one must be able to incorporate the same heuristics into the neural network model.

As we are focusing mainly on generalizable neural network architectures (e.g. a fully connected network, which is what most people think of initially when they hear “neural network”), point (a) is not as relevant here.

To point (b), given that most heuristics are applied equally well to any model (even for something like chess), and the fact that size can sometimes be enough for the network to be able to just learn the heuristic, this first principle regarding neural networks generally holds every time.

This is a rather boring first rule, yet it’s worth stating as an initial point to build up from. While a counterexample doesn’t immediately spring to mind, there’s certainly the possibility that one will arise; for instance, perhaps in specific types of numeric projections. Though it’s not infallible, I have personally not found a way to disprove it empirically, which is a stronger guarantee than what can be said about the following three principles.

2. A neural network can almost certainly solve a problem very similar to ones already solved by neural nets

Let’s say you have a model for predicting the risk of a given creditor based on a few parameters; for instance, current balance, previous credit record, age, driver license status, criminal record, yearly income, length of employment, {various information about current economic climate}, number of children, marital status, porn websites visited in the last 60 days.

Now suppose that this model “solves” your problem, as in it predicts risk better than 80% of human analysts. Alas, GDPR rolls along and you can no longer legally spy on some of your customers’ internet history by buying that data. You now need to build a new model for those customers. Your inputs are now truncated after the customer’s online porn history is no longer available (or rather admittedly usable). Is it safe to assume you can still build a reasonable model to solve this problem?

The answer is almost certainly, “Yes; given our knowledge of the world, we can safely assume someone’s porn browsing history is not that relevant to their credit rating as some of those other parameters.” The problem in question is similar enough to its predecessor that this change will not impact the model’s capacity to solve it.

Now, consider another example: assume you know someone else is using a model, but their data is slightly different from yours.

You know of a US-based snake-focused pet shop that uses previous purchases to recommend products, and they’ve told you it’s done quite well for their bottom line. You run a UK-based parrot-focused pet shop. Can you trust their model or a similar one to solve your problem, if trained on your data?

Again, the right answer here is likely “yes”, because the data is similar enough. That’s why building a product recommendation algorithm was a hot topic 20 years ago, but nowadays, everyone and their mother can simply get a WordPress plugin for it and get close to Amazon’s performance.

Or, for a more serious example, let’s say you have a given algorithm for detecting breast cancer that — if trained on 100,000 images with follow-up checks to confirm the true diagnostics — performs better than an average radiologist.

Can you assume that, given the ability to make this model larger, you can build a model to detect cancer in other types of soft tissue, also better than a radiologist?

Once again, the answer is likely yes. The argument here is longer, however, because we aren’t as certain, primarily due to the lack of data. I’ve spent more or less a whole article arguing that the answer would still be yes.

In natural language processing (NLP), the exact same neural network architectures seem to be decent at performing translation or text generation in any language, as long as that language belongs to the Indo European family and there exists a significant corpus of data for it (i.e. equivalent to that used for training the extant models for English).

Modern NLP techniques seem to be able to tackle all language families, and they are doing so with less and less data. To some extent, however, the similarity of the data and the number of training examples are tightly linked to the ability of a model to quickly generalize to many languages.

We can also consider the problems of image recognition and object detection. For models that tackle these problems, the main bottleneck is large amounts of well-labeled data, not the contents of the image. Edge cases exist, but generally all types of objects and images from various domains can be recognized and classified if enough examples are fed into an architecture originally designed for a different image task (e.g. a convolutional residual network designed for Imagenet), especially when they are visually distinguishable to the human eye. We discuss this point in the next section.

Moreover, given a network trained on Imagenet, we can keep the initial weights and biases (essentially what the network “has learned”) instead of starting from scratch, and it will be able to “learn” on different datasets much faster from that starting point. This is a common practice that manifests in transfer learning and domain adaptation.

3. A neural network can solve problems that a human can solve if these problems are “small” in data and require little-to-no context.

Let’s say that we have 20-by-20-pixel, black-and-white images of two objects that have never been seen before; they are “obviously different”, but are not known to us. It’s reasonable to assume that, given a large amount of training examples, humans would be reasonably good at distinguishing the two types.

It is also reasonable to assume that, given a large number of examples , that almost any neural network of millions of parameters would ace this problem like a human.

You can visualize this in terms of the amount of information that needs to be learned. In this case, for each training example, we have 400 pixels of 255 intensity values each, so it’s reasonable to assume that every possible pattern could be accounted for with a few million parameters in our equation.

But what “small” in data means here is the crux of this definition. In short, how to define “small” is a function of:

- The granularity of the answer (output). For instance, 1,000 classes vs 10 classes, or an integer range from 0 to 1,000 as opposed to one from 0 to 100,000. In this case, we have 2.

- The size of the input. In this case, we have 400, since we have a 20x20 image.

Take a classic image classification task like MNIST. Although a few minor improvements have been made, the state-of-the-art for MNIST hasn’t progressed much. The last 8 years have yielded an improvement from ~98.5% to ~99.4%, both of which are well within the usual “human error range”. Compare that task to something much bigger in terms of input and output size, such as ImageNet, where the last 8 years have seen a jump from 50% to almost 90%.

Indeed, even with pre-CNN techniques, MNIST is basically solvable. However, even having defined “simple” as a function of the above, we don’t have the formula for the actual function. I believe this is much harder, but we can come up with a “cheap” answer that works for most cases:

- A given task can be considered small when other tasks of equal or larger input and output size have already been solved via machine learning with more than one architecture on a single GPU.

This might sound like a silly heuristic, but it holds surprisingly well for most “easy” machine learning problems.

Now, what does “little to no context” mean? This is a harder one, but we can rely on examples with “large” and “small” amounts of context.

-

Predicting the stock market likely requires a large amount of context. One has to be able to dig deeper into the companies to invest in; check on market fundamentals, recent earning calls, the C-suite’s history; understand the company’s product; maybe get some information from its employees and customers; and if possible, get insider information about upcoming sales and mergers, etc. One can try to predict the stock market based purely on indicators about the stock market, but this is not the way most humans are solving the problem.

-

On the other hand, predicting the yield of a given printing machine based on temperature and humidity in the environment could be solved via context, at least to some extent. An engineer working on the machine might know that certain components behave differently in certain conditions. In practice, however, an engineer would basically let the printer run, change the conditions, look at the yield, and then come up with an equation. So, given that data, a machine learning algorithm likely could also come up with an equally good solution, or even a better one.

In this sense, an ML algorithm would likely produce results similar to a mathematician in solving the equation, since the context would essentially be non-existent for the human.

There are certainly some limits to this lack of reliance on context. Unless we test our machine at 4,000 C, the algorithm has no way of knowing that the yield will be 0 because the machine will melt; an engineer might suspect that.

So, this 3rd principle can be stated as “a generic neural network can probably solve a problem if:

-

A human can solve it

-

Tasks with similarly sized outputs and inputs have already been solved by an equally sized network

-

Most of the relevant contextual data a human would require are included in the input data of our algorithm.”

4. A neural network might be able to solve a problem when we are reasonably sure that a) it’s deterministic, b) we provide any relevant context as part of the input data, and c) the data is reasonably small.

Here, I’ll come back to one of my favorite examples — protein folding. This is one of the few problems in science where data is readily available, where interpretation and meaning are not confounded by large amounts of theoretical baggage, and where the size of a datapoint is “small” enough based on our previous definition. The problem can be boiled down to:

-

Around 2,000 input features (amino acids in the tertiary structure), though this means our domain will only cover 99.x% of proteins rather than literally all of them.

-

Circa 18,000 corresponding output features (number of atom positions in the tertiary structure, a.k.a. the shape, needing to be predicted to have the structure).

This is one example. Like most NLP problems, where “size” becomes very subjective, we could easily argue one-hot-encoding is required for this type of input; then, the size suddenly becomes 40,000 (there are 20 proteinogenic amino acids that can be encoded by DNA) or 42,000 (if you care about selenoproteins and 44,000 if you care about niche proteins that don’t appear in eukaryotes).

It could also be argued that the input and output sizes are much smaller, since in most cases the proteins are much smaller, and so we can mask and discard most of the inputs and outputs for most cases. Still, there are plenty of tasks that go from a, say, 255-by-255-pixel image to generate another 255-by-255-pixel image (style alternation, resolution enhancement, style transfer, contour mapping, and so on). Thus, based on this, I’d posit that the protein folding data is reasonably small and has been for the last few years.

Indeed, resolution enhancement via neural networks and protein folding via neural networks came at around the same time (with every similar architecture, mind you). But I digress; I’m mistaking a correlation for the causal process that supposedly generated it. Then again, that’s the basis of most self-styled “science” nowadays, so what is one sin against the scientific method added to the pile?

Based on my own fooling around with the problem, it seems that even a very simple model, simpler than something like the VGGs, can learn something ”meaningful” about protein folding. It can make guesses better than random and often enough come within 1% of the actual position of the atoms, if given enough (135 million) parameters and half a day of training on an RTX2080. I can’t be sure about the exact accuracy, since the exact evaluation criterion here is pretty hard to find, understand, and implement for those who aren’t domain experts. Or perhaps I am just daft, which is a strong possibility.

To my knowledge, the first widely successful protein folding network AlphaFold, whilst using some domain-specific heuristics, did most of the heavy lifting using a residual CNN, an architecture designed for image classification, a task that is seemingly as distantly related to protein folding as it gets. That is not to say any architecture could have tackled this problem as well. It rather means we needn’t build a whole new technique to approach this type of problem. It’s the kind of problem a neural network can solve, even though it might require a bit of looking around for the exact network that can do it.

The other important thing here is that the problem seems to be deterministic. Namely:

- a) We know peptides can be folded into proteins, in the kind of inert environment that most of our models assume, since that’s what we’ve always observed them to do.

- b) We know that amino acids are one component that can fully describe a peptide.

- c) Since we assume the environment is always the same and we assume the folding process itself doesn’t alter it much, the problem is not a function of the environment (note, obviously in the case of in vitro folding, as in vivo the problem becomes much harder).

The issue arises when thinking about(b); that is to say, we know that the universe can deterministically fold peptides; we know amino acids are enough to accurately describe a peptide. However, the universe doesn’t work with “amino acids”, it works with trillions of interactions between much smaller particles.

So, while the problem is deterministic and self-contained, there’s no guarantee that learning to fold proteins doesn’t entail learning a complete model of particle physics that is able to break down each amino acid into smaller functional components. A few million parameters wouldn’t be enough for that task.

This is what makes this 4th most generic principle the most difficult to apply.

Some other examples here are things like predictive maintenance, where machine learning models are being actively used to tackle problems humans can’t, and at any rate not without mathematical models. For these types of problems, there are strong reasons to assume, based on the existing data, that the problems are partially (even mostly) deterministic.

In conclusion

I’ve attempted to provide a few simple heuristics for answering the question, “When should we expect that a neural network can solve a problem?”. This set of principles aims to serve as a general, practical guide for newcomers to the field, or for those who don’t plan to be too involved in ML itself, but have some datasets they wish to work with.

As a recap, these are the takeaway principles we can use to determine when neural networks can be used to solve a given problem.

-

[Near-certainty] If other ML models already solved the problem.

-

[Very high probability] If a similar problem has already been solved by an ML algorithm and the differences between that and the target problem don’t seem significant.

-

[High probability] If the inputs and outputs are small enough to be comparable in size to those of other working ML models AND if we know a human can solve the problem with little context besides the inputs and outputs.

-

[Reasonable probability] If the inputs and outputs are small enough to be comparable in size to those of other working ML models AND we have a high certainty about the deterministic nature of the problem (that is to say, about the inputs being sufficient to infer the outputs).

Coming up with these kinds of rules doesn’t provide an exact degree of certainty, and these rules are also derived from empirical observations. However, I believe they can indeed be applied to real-world problems. In fact, these are to some extent the rules I do apply to real-world problems; for instance, when a customer or friend asks me whether a given problem is “doable”. These four rules are also pretty close to those I’ve noticed other people use when thinking about what problems can be tackled with neural networks. But keep in mind that they are just heuristics, or guidelines, and so aren’t set in stone.