Rights and Regulation: The Future of Generative AI Under the First Amendment

The Supreme Court may soon be willing to grant First Amendment rights to generative AI, which is likely to add to the existing difficulties of passing AI regulation.

Image credit: Archer Amon/Last Week in AI

Overview

- The rise of generative AI and increasing calls for regulation have led a growing number of people to assert that enforcing ethical norms in AIsystem development amounts to “AI censorship”.

- The legitimacy of these claims is weakened as they often fail to take into account the full picture involving AI and freedom of speech, where unregulated technologies contribute to political repression both at home and abroad. Rather than branding all regulation as censorious, it is crucial to understand the legal dynamics surrounding AI speech, and craft policy models that balance the need for ethical AI with the need for free expression.

- By extending speech protections to unconventional forms of expression and applying them to nonhuman speakers, legal precedent largely implies that the Supreme Court may soon be willing to grant First Amendment rights to generative AI, which is likely to add to the existing difficulties of passing AI regulation.

- A variety of legal models are available to target the different concerns that come with generative AI, while also protecting freedom of speech. Several come from examining the parallels between technology regulation and more established areas of law, while others offer new paradigms for understanding the unique nature of AI. We offer five models in particular, each designed for different goals and strategies.

Problem: People are worried about AI censorship.

Beginning in February, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments for Gonzalez v. Google, a case which has the potential to largely redefine the scope of Section 230, the law which provides immunity for online platforms from being held accountable for user-generated content. In a recent meeting, Senate Judiciary Committee members expressed a strong desire to push for stronger platform regulation through a rewrite of the law, and similar cases involving digital platforms and speech rights await consideration from the court, which may come later this year.

While the implications of these cases are massive on their own, the explosive popularity of large language models has generated new questions around how digital speech regulation may impact the development of AI. In the Court’s Gonzalez v. Google arguments, Justice Gorsuch appeared to imply a limit on First Amendment protections extending to generative AI: “Artificial intelligence generates poetry… And that is not protected. Let’s assume that’s right.” Yet when OpenAI’s new GPT-4 model can now outperform 90% of human bar exam takers, this simple assumption may easily be called into question. A multitude of scholars have argued that free speech protections ought to extend to AI, and major First Amendment institutes now argue that laws against deepfake images count as censorship, implying that the line between protected and unprotected algorithmic speech is far from settled.

Concerns over left-wing bias in new AI models have raised a similar (though predominantly unfounded) panic that AI ethicists are imposing a new doctrine of censorship. A December 2022 tweet from tech pundit Marc Andreesen captures just how far this interpretation has been stretched, with the Mosaic co-founder claiming: “AI regulation, AI ethics, AI safety, AI censorship - they’re the same thing.” As discussions around AI become more mainstream, it’s likely that claims of censorship will be raised as a way to delegitimize AI ethics and oppose calls for regulation.

There’s one glaring problem with this claim: it isn’t really about censorship.

Perspective: The risks of protecting AI

It’s one thing to argue against rushing into untested regulations, or to express concerns over the politicization of AI. Yet the attempt to decry AI ethics as a whole raises questions of if these complaints are truly in good faith. Those most concerned about censorship should recognize that better standards for AI development are urgently needed to prevent further suppression of voices. There are numerous examples of AI reinforcing censorship when not properly imbued with ethical standards. Algorithms are known to reflect the political bias of the data they are trained on: For example, sentiment analysis models trained on different national versions of Wikipedia establish different associations for concepts like “democracy” and “surveillance”. As a result, this makes AI vulnerable to being exploited by censorious regimes.

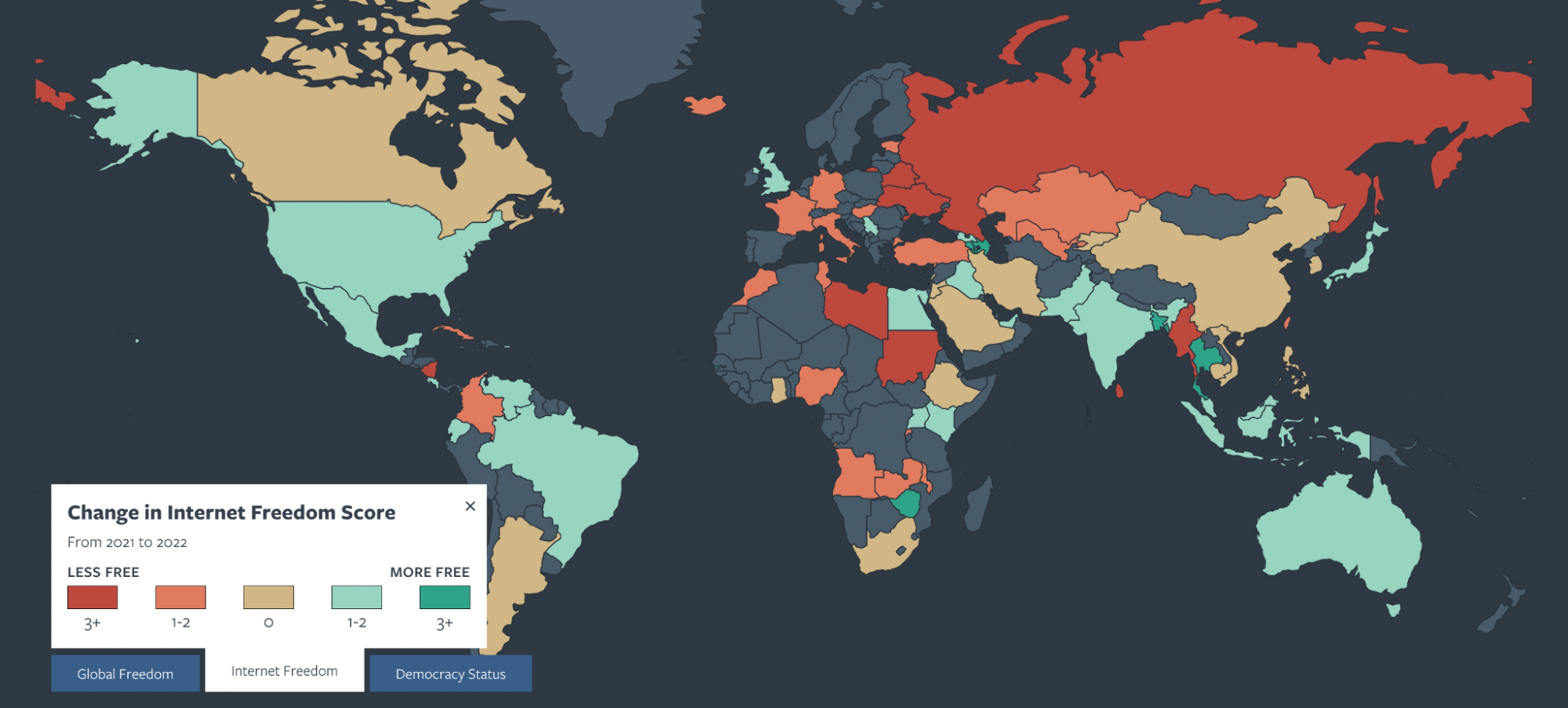

In recent years, a new term has emerged to describe the use of technologies for political surveillance and repression domestically and abroad: “digital authoritarianism”. AI has been used by governments to filter and block websites related to opposition movements and activism, while manipulating social media bots to manufacture artificial support for government leaders, distorting genuine public opinion. Similar threats of AI suppressing speech can be found in democratic nations, with technology providing a new opportunity to massively amplify falsehoods and bury the truth.

Major tech players are often directly implicated in the undemocratic use of AI: In 2020, US companies supplied internet-blocking technologies to Belarus that substantially influenced the nation’s election. Today, Facebook and its parent company Meta face lawsuits for contributing to human rights violations in Myanmar and Ethiopia, along with allegations of supporting censorship in Vietnam. Democratic nations have largely failed to propose a viable model of AI governance, empowering authoritarian actors to exploit this technology. Without adequate regulation, the rapid growth of generative AI is likely to reinforce these problems, as large language models can be weaponized to drown out genuine reporting or facilitate harassment campaigns against journalists. The rapid speed at which AI can be used to create and spread information poses a unique risk in this context when compared to human speakers, as actors may strategically deploy algorithms to maximize engagement, while going largely under the radar due to a lack of traditional legitimacy and accountability.

If censorship were the principal concern, then the silencing of reporters and political dissidents should be at the forefront of the AI discussion. People would be clamoring to pass legislation combating digital authoritarianism, which includes increasing transparency measures for social media companies, establishing clear standards for testing AI platforms, restricting the spread of AI surveillance tools, and more. Yet for much of the anti-regulation crowd, censorship only seems to matter when it’s major tech companies at risk of being censored.

It’s one thing for people to make sensational tweets, but the decision to bring up censorship could have far-reaching consequences for the future of AI regulation, implying that AI-generated content is protected under the First Amendment. Without proper limits, extending constitutional protection to generative AI would give AI companies a broad shield to evade accountability for the harms caused by their models, and the First Amendment defense could be invoked to justify AI-powered harassment and propaganda campaigns. With bias prevalent in up to 38.6% of data used to train many AI models, deepfakes causing growing political havoc worldwide, and numerous other risks posed by large language models,the idea of extending speech rights to them should be scrutinized thoroughly.

Currently, the government is slow to regulate these technologies, though executive agencies appear to be warming up to the idea. But if claims of censorship become too widespread, they could halt action further and insulate the ongoing AI arms race from any number of legislative measures. Many analysts now predict that the year’s largest developments in tech policy will occur in the judicial rather than legislative realm, making it crucial to understand and address the concerns around algorithmic speech before these cases reach their final verdict.

This report thus aims to provide a foundational understanding of generative AI’s future under the First Amendment by examining several key questions around protection and regulation. First, what is the legal case for extending speech rights to the works of AI? Next, how much merit do these claims of censorship hold? Finally, what regulatory options are most likely to remain viable in the event that AI speech gains legal protection?

Whether intentional or not, the censorship concern poses a new challenge for AI ethicists: to demonstrate to the public not only the necessity of regulation, but also the legality of it. Only by understanding and responding to these concerns can we maintain the field’s legitimacy through the age of criticism that is set to come.

Principle: Legal considerations applied to AI

The first step towards understanding how AI could be protected under the First Amendment is to examine the role of AI in the current legal system. Just as people have struggled to agree on a simple definition for what counts as AI, the field of AI law is not easily defined. AI has applications to a variety of fields, including copyright, antitrust law, anti-discrimination law, privacy and security, business law, and more. The list of legal issues which relate to technology is constantly evolving, and questions around tech law can get muddled with other arguments, an issue which some believe is affecting the Gonzalez v Google case.

To establish a clear focus, this report specifically looks at how AI outputs could be protected as speech under the First Amendment. This primarily applies to generative AI, as computer-generated text, images, and other content more closely parallels human expression. However, these protections may also extend to algorithms used for content recommendation and moderation by social media platforms, Netflix, and more. As such, it is necessary to consider the broader legal status of AI speech along with its specific applications.

There is also the issue of how to separate the actions of AI developers from the actions of the algorithms themselves. Different systems are created with different levels of human interference and oversight, and there are a variety of forms that legal recognition for AI-generated speech could take. The works of generative AI could be protected as an extension of the programmer’s speech rights, or as a unique form of expression. In light of these nuances, it is helpful to conceptualize this discussion around AI systems, which involve a variety of steps taken by a variety of actors, including clients, developers, computer programs, and human users. Regulations may thus target different steps along the AI project cycle, from data collection to model design and deployment.

To understand the legal considerations surrounding AI speech and censorship, this report begins with a broad overview of how First Amendment law works as a whole, before examining some of the more unique legal questions which apply to AI, and the history of court cases which provide a roadmap for applying free speech law to AI.

Why is speech protected?

In justifying the right to freedom of speech, legal scholars and justices have primarily referred back to three theories, each with a different primary focus. The most basic theory is the liberty model, which emphasizes an individual’s right to express their opinion as a form of self-realization. The speaker is the most important consideration in this theory, and speech “not chosen by the speaker” or attributable to their values (such as commercial speech) is susceptible to restraint. While this model focuses on the value of speech for the individual, many prevalent theories emphasize the broader societal role of speech protection. The ‘ chilling effect ‘ theory focuses on preventing self-censorship, highlighting how broad or unclear regulations may deter speech beyond what is restricted. The ’ marketplace of ideas ‘ theory takes a further step in focusing on the public listener more than the speaker, and gives the strongest justification for protecting AI-generated speech. Regardless of how it is produced, all speech has the potential to provoke thought and have an effect on the listener. As such, it should be protected so that a listener has access to all viewpoints. The Supreme Court has upheld this principle numerous times, arguing that open public discourse naturally produces competition between ideas where the truth will rise to the top as poor ideas are tested and filtered out.

How is it determined what regulations on speech are allowed?

1. Content-based regulations are hard to defend in court.

Broadly speaking, laws which may infringe on speech freedoms are held to a certain level of scrutiny depending on whether they are content-based or content-neutral. Restrictions which categorize and prohibit speech based on its subject matter or viewpoint are subject to strict scrutiny, which is extremely difficult to overcome: In order to be constitutional, a regulation must use the least restrictive means to promote a compelling government interest, a standard which numerous laws have failed in the past. In 2004, Ashcroft v. ACLU ruled to invalidate the Child Online Protection Act, which would have prohibited content harmful to minors from being posted on the web for commercial purposes. While the government had a compelling interest in promoting child safety, the court determined that less restrictive alternatives were available and similarly effective, such as promoting the development and use of content-filtering software. The prohibition was ended, prompting the government to consider and implement two alternative measures: a prohibition on misleading domain names, and a minors-safe ‘dot-Kids’ domain.” While the field of internet law has grown considerably since 2004, it is not difficult to see how the same basis of standards may apply to regulation of harmful AI-generated content.

2. Content neutral regulations are more acceptable, but must be designed carefully.

Content-neutral regulations are divided into two main categories, each subject to intermediate scrutiny. The first category concerns regulations on the time, place, and manner of speech (TPM regulations). For example, a city may require a permit for using a megaphone or wish to implement a buffer zone around healthcare facilities such as abortion clinics. For these regulations to be upheld, they must be “justified without reference to the content of the regulated speech,… narrowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest, and… leave open ample alternative channels for communication of the information”.

The second category concerns regulations on expressive conduct rather than pure speech, which are subject to the O’Brien test. Derived from a court case involving the burning of draft cards, the O’Brien test allows for certain regulations which may incidentally limit speech A regulation is permissible if it furthers an important government interest unrelated to the suppression of free expression, and prohibits no more speech than strictly necessary. Speech may be left unprotected as it crosses the line into conduct: For example, distributing a computer virus is different from publishing a website. Certain categories of speech are also generally exempt from protection: obscenity, fighting words, defamation, child pornography, perjury, blackmail, incitement to imminent lawless action, legitimate threats, or solicitations of criminal activity.

3. The principle of prior restraint: You can’t restrict speech before it’s said.

In any circumstance, unprotected speech may be punishable after the fact, but speech typically can not be restricted prior to its release (For example, a law requiring a newspaper to approve articles with the government before publication would be unconstitutional ). Some argue that content filtration systems constitute a prior restraint by blocking speech before it goes live (although the censoring agency is typically not the government). Similar concerns are relevant in regulating the deployment of AI — to what extent could requiring programmers to go through extra procedures to ensure the safety of their algorithms constitute a prior restraint? Drawing the line between accountability measures and unfair restraints will require a nuanced discussion of the circumstances surrounding AI development.

How can we understand algorithmic speech?

Technological advancement has surfaced new models of thinking about speech and censorship which are helpful in discussing how concepts of speech and censorship may apply to AI.

While the First Amendment is designed to protect speech in public forums, it is becoming increasingly difficult to “impose a rigid distinction between public and private power to understand digital speech today”. Digital infrastructure providers are private companies, but they play a unique role separate from both conventional editorial organizations and public forums. In today’s pluralist model of speech and regulation, speech is filtered and controlled not only by governments, but by private infrastructure. Digital networks may simultaneously empower and stifle free speech, and the government takes on a complex role of regulating these intermediary providers rather than direct speakers. The digital age incentivizes platforms to create their own systems of private governance and content moderation, while government pressure on social media companies raises concerns of “ censorship by proxy. New technologies have created a “ hybrid media system “ which may require its own set of legal considerations: many social media platforms play a variety of roles, from news to entertainment and political assembly. Attempts to compare algorithmically-run platforms to traditionally-curated media like magazines or cable news can only go so far, as today’s media cuts across a variety of distinctions.

Much discussion concerns the impact of algorithms for filtering and amplifying speech, but more considerations become relevant when AI creates speech of its own. In these circumstances, is it the AI’s speech or the programmer’s speech that is subject to protection? Because AI lacks agency in the traditional sense, scholars have typically viewed algorithms as representing the agency of their creator. Yet this raises a host of other questions: Is the programmer responsible for everything an AI produces? If it generates harmful or illicit content, can we hold them responsible as we would a direct speaker? What happens when a system is created by a large team of people?

In determining whether AI is entitled to speech rights, the autonomy of the speaker may not be as important as the autonomy of the listener. Focusing on speaker autonomy requires identifying specific characteristics unique to humans, and proving that those qualities are important to free speech protections (an increasingly difficult job as technological progress advances). Yet human listeners and readers of AI speech also have the autonomy to develop their own beliefs and “determine if the speaker is right, wrong, useful, useless, or a badly programmed bot”. Similar to the marketplace of ideas theory, the concept of reader response criticism posits that the reader should be at the center of efforts to protect speech. Even randomly generated words or pictures can be ascribed meaning without intending to send a certain message, which proves the value of expression is at least to some degree separate from autonomous intention.

How do existing legal precedents and norms extend to AI?

The idea of affording First Amendment rights to AI is not merely a theoretical one. Years of legal precedent suggest that the Supreme Court would be poised to extend the First Amendment to encompass AI-driven activity. Recent cases have refuted many objections that may stand in the way of applying speech rights to AI, such as concerns over its clarity of message, interactive nature, and ever-evolving technological features. At the same time, lower court decisions have largely absolved algorithmically powered search engines from liability, a verdict that may soon cover chatbots and image generators as well.

The following table summarizes the main legal developments which could provide a rationale for extending free speech protections to AI. A more extensive list of lower court rulings pertaining to AI can be found here. While a few recent decisions have begun to indicate that certain aspects of AI may not be protected by the First Amendment, a substantial reversal in precedent would be needed to defend many common regulations in the case of a First Amendment controversy.

Table 1: Legal Precedents for Protecting AI Speech

| CASE | BACKGROUND AND PRINCIPLES ESTABLISHED | IMPLICATIONS FOR AI |

|---|---|---|

| Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. Federal Communications Commission Supreme Court, 1994 (Turner I), 1997 (Turner II) | Background As a result of ‘must-carry’ laws, “Federal legislation requires cable television companies to devote a portion of their channels to local programming.” The court ruled 5-4 in favor of the FCC. Principles Turner I: Cable providers are First Amendment speakers, even though they don’t directly generate the content being shared. Turner II: ‘Must-carry’ laws are content-neutral regulations, as they only have to do with the number of channels a company has to offer. |

A message only needs to meet minimal conditions to be seen as communication, which allows algorithmically-powered search engines or generative AI to be classified as speakers. However, content-neutral regulations on AI may still be viable. For example, a provision requiring internet platforms to reserve space for human-generated content could be seen as a permissible regulation similar to ‘must-carry’ laws. |

| Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston, Inc. Supreme Court, 1995 | Background Organizers of a St. Patrick’s day parade in Boston denied the Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston (GLIB) from participating in the annual parade. The question arose of if the parade — a public event organized by a private group — had the right to control the message being sent, or if excluding GLIB constituted a violation of anti-discrimination laws. The court ruled unanimously in favor of the Veterans’ Council organizing the parade. Principles Speech protections can be given to activities lacking a clear, coherent message, such as parades: “A narrow, succinctly articulable message is not a condition of constitutional protection, which if confined to expressions conveying a ‘particularized message,’ would never reach the unquestionably shielded painting of Jackson Pollock, music of Arnold Schoenberg, or Jabberwocky verse of Lewis Carroll.” |

Algorithmically-generated speech contains a certain degree of randomness, and the code for an AI system may not contain a clear intentional message. The ruling establishes, however, that this does not rule it out from obtaining First Amendment protection. While an AI may lack a clear message as a whole, the speech it creates may still be protected. Similarly, the fact that AI systems are often created by large teams rather than an individual “speaker” does not leave them free from protection, as a large parade gathering can still be justified as protected speech. |

| Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission Supreme Court, 2010 | Background Nonprofit corporation Citizens United argued the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 to be unconstitutional, seeking to distribute a film critical of Hillary Clinton, which the act prevented them from doing. The BCRA, designed as an anti-corruption measure, prohibited corporations from using their money for “electioneering communications” within 30 days of a primary election (or 60 days of a general election). The court ruled 5-4 in favor of Citizens United. Principles First Amendment protection can apply to corporate political spending. Three main aspects of the court’s decision are particularly relevant here: First, the Supreme Court expressed a desire to give the benefit of the doubt to protecting speech: “Rapid changes in technology—and the creative dynamic inherent in the concept of free expression—counsel against upholding a law that restricts political speech in certain media or by certain speakers.” Second, it rejected the distortion argument that corporate spending would distort public discourse, taking a narrow view of corruption. Third, this decision afforded corporations the same speech rights as individual people, with Justice Scalia arguing “the \ [First] Amendment is written in terms of ‘speech,’ not speakers. Its text offers no foothold for excluding any category of speaker, from single individuals to partnerships of individuals, to unincorporated associations of individuals, to incorporated associations of individuals.” |

In extending speech protections to non-human entities such as corporations, Citizens United established a precedent that could easily be used to further extend those protections to AI. The “speech, not speakers” argument combined with the reluctance to censor new technology suggest that the court would be likely to afford similar rights to AI. In the case of Citizens United, the court argued that corporate influence would not have a detrimental impact on democracy reasoning that “the public would be able to see who was paying for ads and ‘give proper weight to different speakers and messages.’” Yet in practice, the source of political funds has remained largely obscured due to the growing influence of super PACs and dark money. Generative AI stands to have an even larger distortionary effect on public discourse and culture, as it is able to produce content at far greater speeds than even large corporations. It also has the potential to exacerbate corporate influence as the costs of running advanced language models increases. Special watermark tools and bot identification laws may allow people to differentiate AI from human-generated content, but still face issues in their implementation, and may not fully solve the distortion problem. There are still barriers in the way of applying Citizens United to AI speech. Corporations are still composed of individual humans making decisions, a factor which likely influenced the Court’s decision. Even Justice Scalia’s listed categories of speakers fail to encompass autonomous systems. The unique circumstances raised by AI may suggest a more nuanced and limited application of Citizens United: “the Court may determine that an AI is eligible for free speech protection only if it contains some form of human input or presence.” |

| Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association Supreme Court, 2011 | Background A trade association of video game merchants questioned the constitutionality of a California law prohibiting the sale of violent video games to minors. The court ruled 7-2 in favor of the Entertainment Merchants Association. Principles Free speech principles should remain constant even in the face of new technological developments: “Whatever the challenges of applying the Constitution to ever-advancing technology, ‘the basic principles of freedom of speech and the press, like the First Amendment’s command, do not vary’ when a new and different medium for communication appears.” Furthermore, the interactive nature of video games does not leave them free from protection. |

Even as technological developments change what speech means in practice, the Court has largely taken the strategy of extending existing speech protections to new forms of expression without majorly revising its concepts of speech freedom under the First Amendment. Artificial intelligence represents a further technological advancement which may call for rethinking traditional ideas of speech, and it is up to the Court to determine how these “basic principles” will be interpreted as these advancements progress further. Generative AI also frequently exhibits an interactive quality as do video games, which is shown not to rule it exempt from First Amendment coverage. |

| Zhang v. Baidu.Com Inc. United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, 2014 | Background Advocates for democracy in China claimed that Chinese search engine Baidu unlawfully censored pro-democracy content from appearing in US search results. The district court ruled in favor of the defendant, Baidu. Principles Search engine results are a form of protected speech which may be largely exempt from regulation: “search engines inevitably make editorial judgments about what information… to include in the results and how and where to display that information” in a way similar to other protected editorial media. |

By arguing that search engine bots produce speech, the case sets a standard that, if affirmed by other courts, could easily be applied to other algorithms such as chatbots. In fact, the case has already been cited as a precedent in multiple relevant cases involving regulation of search results and social media algorithms. The Supreme Court may eventually set a different standard, but as established in past cases, this is unlikely given the court’s current attitude surrounding free speech and new technology. |

| Heffernan v. City of Paterson Supreme Court, 2016 | Background Heffernan, a city police officer, was demoted after a misunderstanding led his employer to believe he was supporting a mayoral candidate the department opposed. Heffernan argued his First Amendment rights had been violated despite not having actually exercised his right to free speech. The court ruled 6-2 in favor of Heffernan. Principles Free speech is largely about preventing excessive government control. Attempting to suppress speech is seen as harmful even when the actual speech in question does not exist: “the Court still sanctioned the government… because of its speech-suppressing motive even though the employee had not engaged in protected speech.” |

This case upholds a negative interpretation of the First Amendment, which focuses on preventing government suppression, as opposed to the positive interpretation of uplifting and promoting speech. Whether the Court chooses to prioritize positive or negative freedoms substantially impacts how they may view AI in the future. Under the concept of positive freedom, AI ought to be regulated more to empower human speakers and ensure their voices are heard. Otherwise, the prevalence of bots may become a threat to human freedom. Under the concept of negative freedom, however, limiting AI speech may be seen as an unjustified restriction and an overreach of government power. If First Amendment rights apply to speech that does not exist, the Court may strike down regulations of possible technology even when the AI in question hasn’t yet been developed. |

| E-Ventures Worldwide, LLC v. Google Inc. United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida, 2016 | Background SEO provider e-ventures claimed Google had removed its websites from search results with the intention of hurting its competitor. Google, who claimed the websites were spam, argued that its search results were pure “opinions” and “editorial judgements” protected under the First Amendment, leading e-ventures to bring forth a lawsuit alleging false commercial speech and unfair trade practices The district court ruled in favor of Google. Principles The court determined that the Communications Decency Act did not exempt Google from liability for false commercial speech and unfair trade practices when removing its competitor’s content. However, Google’s actions were determined to be protected speech as it was “akin to a publisher, whose judgments about what to publish and what not to publish are absolutely protected by the First Amendment.” |

While this case fulfilled an important role in establishing the limits of where the Communications Decency Act may exempt a provider from liability, it also worked to effectively give search engines complete control over their content, making regulation all but impossible. It is uncertain how this ruling might apply to generative AI, which functions with more complexity and autonomy than conventional search engines. While Google’s search engine contains over 200 ranking factors, ChatGPT’s 175 billion parameters may be even harder to find publisher-like judgements reflected in. However, the ruling largely indicates that results produced by algorithms are no less protected by the First Amendment than those which are purely human-generated. |

In the status quo, legal precedent suggests that the First Amendment freedom of speech applies in large part to AI-generated content. The principal issue, however, isn’t just whether AI really has speech rights, but whether those rights will be used to excuse injustice and shield AI companies from accountability. With these concerns in mind, some scholars argue that the extension of speech protections to fully nonhuman actors demonstrates that the idea of free speech has perhaps gone too far, or needs substantial reworking for the modern age.

PITFALLS: Barriers to regulation

Without sufficient limiting principles in place, the dangers posed by unregulated AI may call for legal scholars to rethink the First Amendment’s role in the technological age, or draw an arbitrary line to exclude AI from its coverage. Yet beyond the established legal challenges, there are a few additional factors which make the harms of AI particularly difficult for governments to address.

Good regulation can be difficult.

AI systems have wide-ranging impacts across a variety of sectors, such as healthcare, education, security, economics, and ecology, to name a few. When innovations such as large language models are repurposed for a variety of uses, it may be difficult to understand the technology’s systemic impacts from one case alone. While some have advocated for more centralization in mitigating technology’s potential for harm, effective crafting AI regulations often requires nuanced technical expertise and sector-specific knowledge. Different regulations may need to be developed for different use cases of AI, and new innovations develop much faster than legislation can be made. To add to the problem, many congresspeople are alarmingly uninformed about technology, and competition against actors like China leads to concerns that regulation would simply slow down progress.

Bad regulation can be dangerous.

Poorly designed regulation or misguided legal arguments could have unintentional consequences. For one, unclear regulation risks leaving other areas of speech unprotected. Automation exists on a continuum, and it’s hard to determine when something becomes automated enough to change traditional ideas of speech protection. Take the example of a person setting up a physical bulletin board to display articles concerning certain words. While their opinion on the articles may not be clear, the process of displaying them indicates a judgment about what is deserving of public attention. If they move to create a virtual bulletin board, and then later automate the collection of articles through a program, does it ever stop being protected speech? Arguably not. Today’s algorithms are trained with enough data that a clear judgment of what is deserving of attention may not be as obvious. Yet if AI regulation is not clear and well-defined, it could leave forms of expression such as bulletin boards or magazines vulnerable to censorship. At the same time, weak legislation could afford undue protection to harmful technologies such as deepfakes. Regulations must be narrow enough to target the threats posed by AI without containing ambiguity that could be used to suppress protected speech. Too much state control of AI could reinforce the issues of authoritarianism that the field of tech ethics is meant to fight. On a global level, increasingly restrictive policies could create a “race to the bottom” in which standards are set by the most censorious regime, as the globalized nature of digital technologies makes it possible for countries to extend their censorship efforts beyond their own borders.

Between the dangers posed by excessive regulation and the challenges of navigating around the First Amendment, people’s reluctance to address the harms caused by AI is not fully unfounded. Yet there are a myriad of policy options to consider, from modifying the technology itself to establishing legal frameworks for accountability and transparency. To hastily generalize them all as censorship ignores the ways in which unregulated AI can itself repress citizens and silence voices in the political sphere. Overhyping AI without regard to its consequences will not be enough to preserve freedom in the digital age, as this powerful technology falls further into the hands of undemocratic or profit-seeking actors. Instead of dismissing AI ethics as a whole, free speech advocates can play a productive role in shaping the conversation around AI alignment. Political figures need nuanced suggestions to create an effective system of AI governance while respecting the principles of speech freedom and autonomy. The following section attempts to provide a justification in line with existing precedent for partially limiting the freedoms afforded to AI, while illustrating a variety of policy models worthy of consideration.

POLICY: Options for constitutional AI regulation

In outlining the pathways that would allow AI speech to be protected under the First Amendment, several legal scholars have made the disclaimer that while these principles would logically extend to AI-generated outputs, doing so in practice would be harmful. Recognizing AI as a full speaker may prevent basic measures such as bot identification laws from going into effect, severely limiting the regulatory options available. These scholars are right to focus on the policy implications that any legal ruling around AI would have: these discussions need to be framed as a matter of functional policy, rather than appealing to rights-based arguments. Focusing on rights would frame the discussion around AI speech as a system of individual duties and effects, where a specific individual has a right to claim. Yet the impacts of AI are hard to reduce to “binary interpersonal relations”: a variety of actors and effects are involved, and traditional conceptions of rights may not be suited to include nonhuman entities. Focusing more on policy impacts is likely to prevent people from anthropomorphizing generative AI.

However, it is not enough to warn of the harms that come with protecting chatbot speech. What matters first and foremost is designing a plan of action that will allow for limitations on AI speech to pass judicial review. With this understanding, our next step is to develop a rudimentary framework that encourages constructive dialogue among technologists, scholars, citizens, and policymakers regarding the freedoms and limitations afforded to generative AI. This list of proposals is not exhaustive, and further exploration into the harms and benefits of each is necessary. Yet bringing these ideas to light is essential: The panic around “AI censorship” today indicates a lack of imagination in public discourse. To get past these blanket claims, we must offer clear suggestions of how to reconcile AI regulation with legal principles.

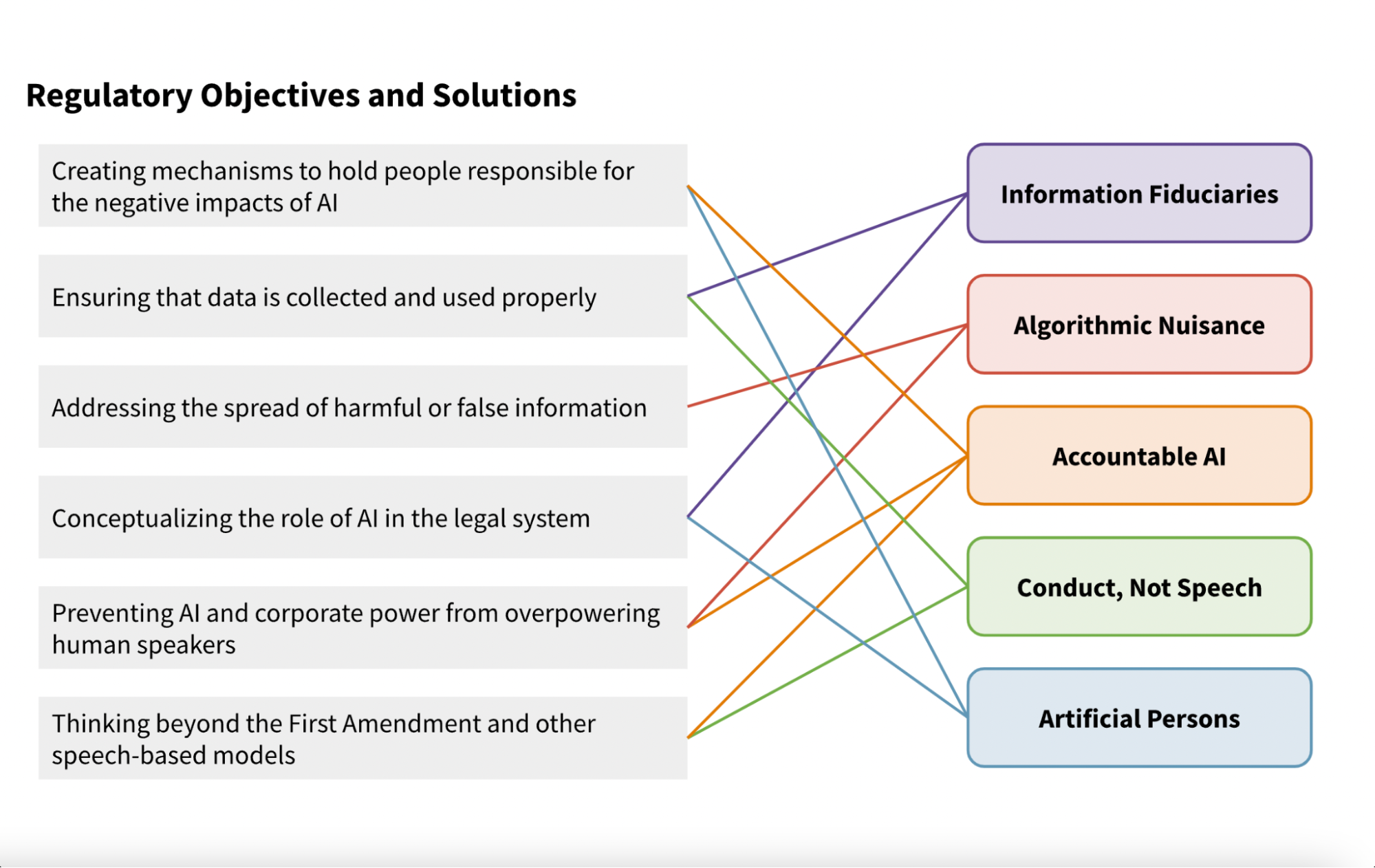

What legal models and justifications could be used to regulate generative AI?

Legal scholars and AI policy researchers have surfaced a variety of proposals which may offer a new opportunity to legislate and adjudicate matters surrounding AI. Some are extensions of established models, while others aim to offer a new paradigm for thinking about AI under the law. This report highlights five of these ideas, though many more are certain to exist.

1. The “information fiduciary” model — Regulate AI’s obligation to users in a way similar to other professional duties.

Unique models of speech regulation and guidance have been developed for certain professional roles: for example, a doctor must protect patient privacy, and a lawyer must faithfully represent their client. People in these professions are designated as “information fiduciaries”: they have a certain responsibility to protect and wisely handle the information that is given to them by a client. As a result of the special relationship between the client and provider and the complexity of the work undertaken, these expectations are necessary to ensure the professional in question acts in good faith.

Recently, legal scholars have proposed that this concept of a fiduciary relationship (where one entity acts on behalf of another) might be applied to digital platforms, particularly those that handle user data. Generative AI technologies often act on behalf of one or more individuals, from the developer creating the code to the users supplying prompt requests. Furthermore, they are frequently trained on data which is sensitive in one way or another (take the example of AI image generators trained on copyrighted artwork). The OpenAI charter even appears to recognize the applicability of this concept, stating “our primary fiduciary duty is to humanity.”

While the limits of this fiduciary relationship may not be as clear as in the case of a doctor or lawyer, it provides a useful framework for justifying AI regulation under the First Amendment. Just as an attorney should not misrepresent their client in court, an image-generation model creating a harmful deepfake may be seen as misrepresenting the individual(s) whose images it was trained on. A text generator like ChatGPT spewing misinformation could be viewed similarly to a doctor misleading a patient (a comparison which becomes especially relevant as large language models get adapted to the medical sector). Regulation using this concept would be in line with a listener-based model of speech regulation, emphasizing a user’s right to receive fair and trustworthy information. Existing First Amendment doctrine also notes that speech protections are not extended to “actors who handle, transform, or process information, but whose relationship with speech or information is ultimately functional”, which may provide further justification for limiting the First Amendment protection of certain algorithms (though this remains a difficult task under Section 230 ).

2. Preventing “algorithmic nuisance” — Limit AI’s ability to amplify speech through time/place/manner regulations modeled after public nuisance law.

One unique characteristic of AI and other digital technologies like social media is the ability to amplify certain viewpoints. AI produces writing at much faster speeds than humans, and with bots already accounting for at least a quarter of activity on platforms like Twitter, it’s not hard to imagine a future in which the internet is overrun by algorithmically generated content. To address these circumstances, content-neutral regulations could attempt to limit AI’s ability to amplify speech. Limits on speech amplification are commonly allowed under the First Amendment as TPM restrictions, like requiring a permit to use a megaphone. They also relate to the concept of public nuisance: a subsection of tort law which has increasingly been extended to cover a variety of unconventional damages.

While the argument that speech regulation can prevent distortion of the public sphere was rejected in Citizens United, it may hold merit in the case of generative AI: text or images are more clearly understood than political spending in the context of speech rules, and the idea of “algorithmic nuisance” may build upon existing cybertort law. Algorithmic nuisance refers to the idea that the data collected and manipulated by algorithms has an outsized and often nonconsensual impact on people’s personal lives, like when Big Data algorithms are used to screen job applications, influence credit scores, and more. The effects of these algorithms are cumulative and longstanding, bearing similarity to traditional forms of nuisance like pollution. Along with protecting individuals, nuisance law fulfills the economic function of preventing companies from “externaliz [ing] the costs of their operations onto strangers.” When generative AI technologies limit public access to organically created content, they too leverage a broad social cost that may be remedied through nuisance law. By appealing to a public right to receive information, legal professionals and regulators could develop new interpretations of nuisance law to specifically target the issues posed by content production algorithms.

3. “Accountable AI” — Empower individuals to resist AI by establishing clear pathways for legal action and creating better requirements for transparency.

The debate around generative AI will continue to be shaped by public norms and understanding. In the absence of a strong legal framework, it is this public that plays a substantial role in informing or resisting the development of new technology. Basic conceptions of free speech, like the marketplace of ideas theory, similarly revolve around the idea that public discourse and group efforts will shape the development of intellectual thought and the progression of ideas. As such, it is the role of law to empower individuals to understand and critically engage with AI systems. Law has always worked to facilitate or prevent citizen action, from providing clear language for bringing forth lawsuits to establishing clear processes for redress and remedies. This may include leveraging orders through injunctions or clearly defining monetary damages that can be sought. A more potent example is algorithmic disgorgement, an enforcement tool established by a Federal Trade Commission settlement last year that calls for the full destruction of improperly obtained data and models built with it.

In the case of AI and digital technology more broadly, new laws are needed to promote standards of transparency, agency, and due process. By developing standard metrics for auditing and benchmarking these technologies, jurists can clearly establish when malpractice has occurred, and regulators can take a more informed approach in developing new laws. These standards should be developed to seek transparency both in the use of fundamental models and the outcomes created by AI.

States should also explore specific legal frameworks and dispute resolution mechanisms for handling cases involving AI. The Algorithmic Accountability Act, introduced in the US Senate in 2022, provides a good starting point for improving transparency. The landmark bill “requires companies to assess the impacts of the automated systems they use and sell, creates new transparency about when and how automated systems are used, and empowers consumers to make informed choices about the automation of critical decisions”, along with improving the capability of the FTC to enforce these provisions.

4. “Conduct, not speech” — Target data collection rather than expression of it, regulating more of the actual resources used to make the AI.

The outputs of generative AI models share many characteristics associated with traditional speech, affording them a certain level of protection under the First Amendment in the status quo. Yet the development and use of these technologies involves a variety of activities beyond producing speech: data collection, labeling, system design, advertising, and often commercialization. Many of these activities cross the line into conduct rather than pure speech. Specifically targeting these non-speech actions may provide a safeguard against some of AI’s most odious potential harms, while reducing the viability of First Amendment concerns.

The doctrine of prior restraint mentioned earlier prohibits governments from taking measures to restrict speech or other expression before the activity in question actually occurs. For example, they cannot require that the contents of any publication receive government approval before being released. Even with this principle, it remains possible for certain activities to be restricted even if their end goal is to produce speech.

Wiretapping and other forms of surveillance are largely restricted by federal and state laws, even when doing so may advance journalistic interests. Similarly, freedom of speech may afford someone the ability to talk about a company, but not to steal or leak trade secrets in the process. Despite the difficulty in enforcing anti-piracy laws, it remains a crime to illegally download a copyrighted movie, even if one’s ultimate objective is to write and publish a review of it.

Content warning: the following paragraph talks about pornography and sexual violence. To skip past the discussion of this subject, move to the paragraph afterwards, beginning with “Recent lower-court cases…”

Even if the First Amendment is extended to protect AI-generated work, some of the technology’s most odious potential harms may be fought by targeting the collection of data rather than the publication of it. This concept applies especially well to image-generation software. Take the example of pornographic deepfakes, which account for an estimated 90-95% of deepfake content on the internet. The current legal system largely views these image manipulations in a separate category from other nonconsensually shared images, despite the fact that they induce the same traumatic harms to those targeted. While a few states have passed laws to officially criminalize the use of this technology, other scholars have made the argument that explicit deepfakes are likely protected under the First Amendment, as dystopian as it may be. There is a plausible risk that future perpetrators may try to use a First Amendment defense to argue for the legality of such acts. If this worst-case scenario comes into play, the most effective approach may be to criminalize the AI’s collection and distribution of these images, beyond focusing on the manipulation of the image as speech.

Recent lower-court cases offer hope that the First Amendment will not give unrestricted protection to biometric data collection and surveillance, a landmark step in working to maintain user privacy and dignity in the age of artificial intelligence. ACLU v. Clearview AI, a case argued in an Illinois state court last year, demonstrates that First Amendment protections will not fully allow tech companies to violate certain privacy standards. The court in question refused to dismiss the lawsuit brought against Clearview under the Illinois Biometric Privacy Act (BIPA), despite the company having claimed that its actions were protected under the First Amendment. The lawsuit accused Clearview of violating BIPA’s requirement that companies notify and obtain the consent of any state resident whose data they collect. Clearview — whose faceprint records include over 3 billion images and have been shared with a variety of actors including government and law enforcement — argued that its business practices were protected under the First Amendment, likening its data collection and analysis to search engines, which are largely protected. The court, however, did not buy this argument, rejecting the motion to dismiss the lawsuit.

The case was resolved with a legal settlement which marks one of the most significant recent court actions for protecting individual data privacy, and is likely to have national precedent impacts. The settlement permanently bans Clearview from selling its enormous faceprint database to any entity in the nation, with limited exceptions. It establishes a five-year prohibition on Clearview granting access to any government entity in Illinois, designating that its activities are not covered under BIPA’s exceptions. Furthermore, it requires Clearview to maintain and advertise an opt-out request form on its website, and continue taking measures to filter out the data of Illinois residents.

The settlement reached in ACLU v. Clearview is a major success, and its achievement may encourage other states to adopt similar privacy laws. While this case specifically targets a classifier model rather than a generative one, legislation like the BIPA could likely be used to prevent other commercial uses of sensitive data without subject consent, thus providing an avenue to fight against deepfakes and other harmful applications of AI. By focusing on system inputs rather than the works generated, litigators can shift the battle to focus on physical harms rather than speech harms and interests.

5. “Artificial persons” — Establish stronger accountability requirements by granting AI systems a limited degree of legal status.

As much as they may be anthropomorphized in popular dialogue, AI systems are not people. Yet the concept of personhood before the law may provide another way to reconcile the changes brought by AI with existing legal structures. To start, understand that legal personhood is not the same as natural personhood: corporations are a prime example of a non-human entity that is treated as a legal person, allowing for them to sue and be sued, enter into contracts, and own property. Legal personhood has also been proposed for animals, the natural environment, marine vessels, celestial bodies, and most recently, artificial intelligence systems. While the exact structure varies from one case to another, the basic idea is that legal personhood allows for an entity to be conceptualized more clearly in the eyes of the law, which could mean ascribing certain duties or protections to it.

One option is dependent legal personhood, which is typically granted to children. Similar to AI systems, children make active decisions, but are also entrusted to the care of a parent or legal guardian. Extending dependent legal personhood status to AI would allow for a way to attribute responsibility to those in charge when AI commits certain harms. The German law concept of Teilrechtsfähigkeit provides one example of partial legal subjectivity which may be afforded to AI or intelligent agents like animals. Laws can also take into account the unique circumstances of AI as an inanimate entity: while an AI can not be conventionally ‘punished’, it may be “physically disabled, barred from future participation in certain economic transactions, deregistered, or have its assets seized.”

There are some notable issues with extending legal personhood to AI, both in terms of technical difficulty and concerns that it might backfire, allowing companies to evade accountability by granting an exaggerated level of agency to the AI. Still, a nuanced application of the concept could resolve many of the current deficiencies in existing law while tailoring these policies specifically to the needs of AI. The key idea is that scholars and advocates should work to delineate what this legal status looks like and use it as a proactive tool before others attempt to exploit it as a defense.

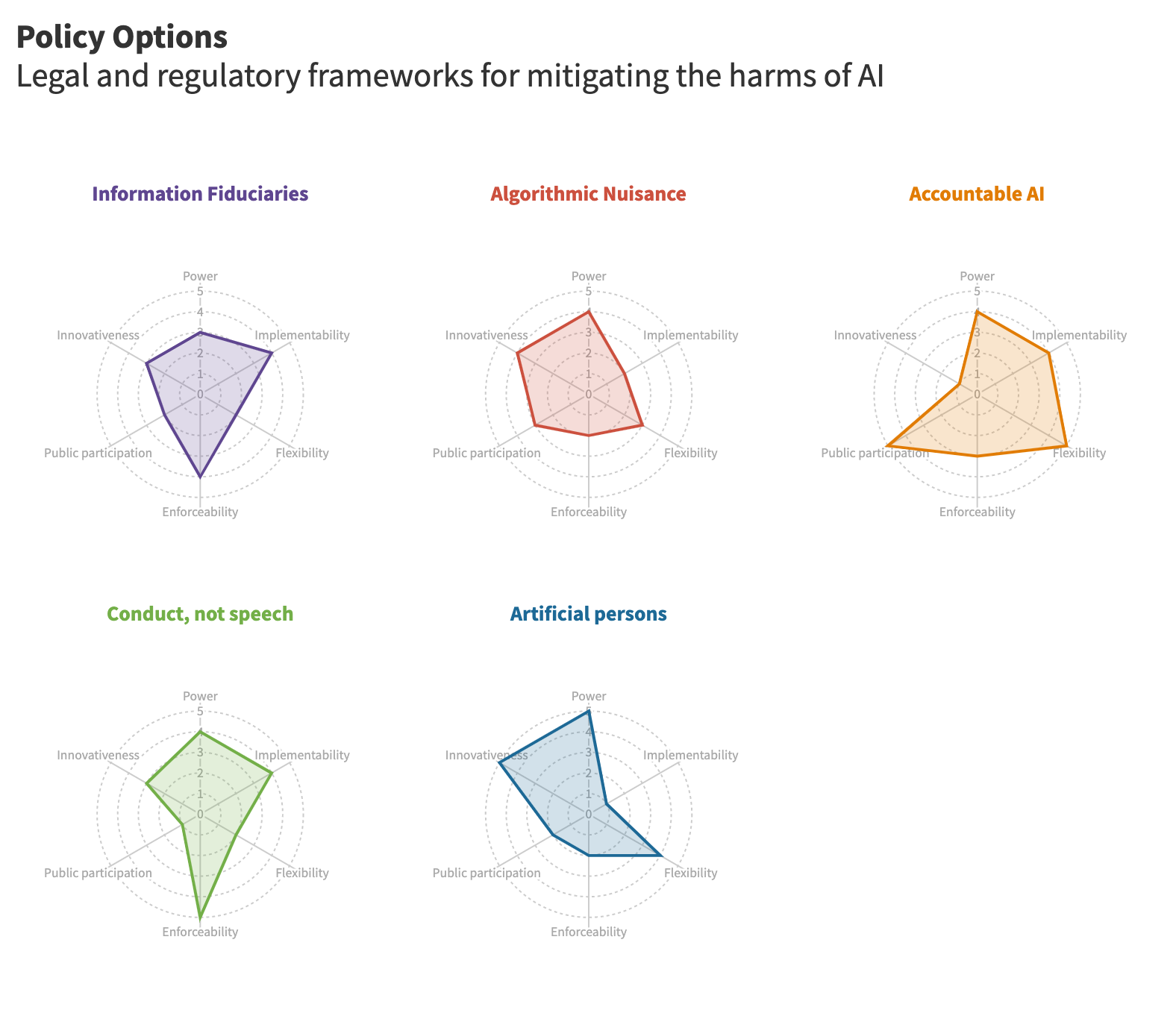

Each of these policies will come with its own set of considerations, and the effectiveness of each largely depends on the details of how it is designed and implemented. This chart is designed to offer a simple visualization of the potential strengths and weaknesses of each model, based on initial predictions and assessment of the current regulatory landscape.

In conclusion

With the capabilities of generative AI expanding further every day, these policies may not be a full solution to the questions of the future. The battle over AI’s First Amendment privileges largely waits to be fought in court, and these decisions may change the tech policy landscape in ways that none of us are prepared for.

Yet behind the outcries over AI censorship and regulation today are a few key truths: Free speech law will become increasingly relevant to the growth of generative AI. Legal precedent may allow the First Amendment to protect AI-generated speech, or justices will draw a line in the sand. Affording constitutional protection to AI will not come without its harms — by limiting the options available for regulating these technologies, it may suppress the voices of human speakers both domestically and around the globe. Either way, regulating AI speech is no easy task, and several considerations must be taken into account, both for speech freedom and other purposes. In light of these challenges and concerns, new policy models can work to reconceptualize how AI is seen under the law, and how its harms can be prevented while uplifting freedom for all.

Offering these proposals is only the first step. Passing them as law or arguing them in court is a different battle, and it is one that each of us can contribute to. The private sector can take steps to design AI systems with harm reduction in mind, and set internal standards of transparency, fairness, and accountability. Robust corporate governance models can inspire a healthier atmosphere for AI development and reduce the need for arduous legal battles. AI ethicists can develop creative policies for guiding the development of generative AI, and work with policymakers to put them into action. Meanwhile, those who are skeptical of AI ethics can identify which specific policies they oppose, and offer alternative solutions of their own. Scholars and community members can shine light on these discussions, expand on these ideas and offer new perspectives to them.

At a time when robots can be exploited for authoritarian agendas, weaponized against journalists, or used to silence marginalized voices, AI ethics is not antithetical to the free expression of ideas. Instead, it is an indispensable tool for safeguarding them. If we wish to create a healthy environment for AI development and adoption, we cannot demonize the field of AI regulation in the name of free speech — Rather, we must work to create new modes of technology governance in line with it.