The Past, Present, and Future of AI Art

AI art has a long history that is often overlooked

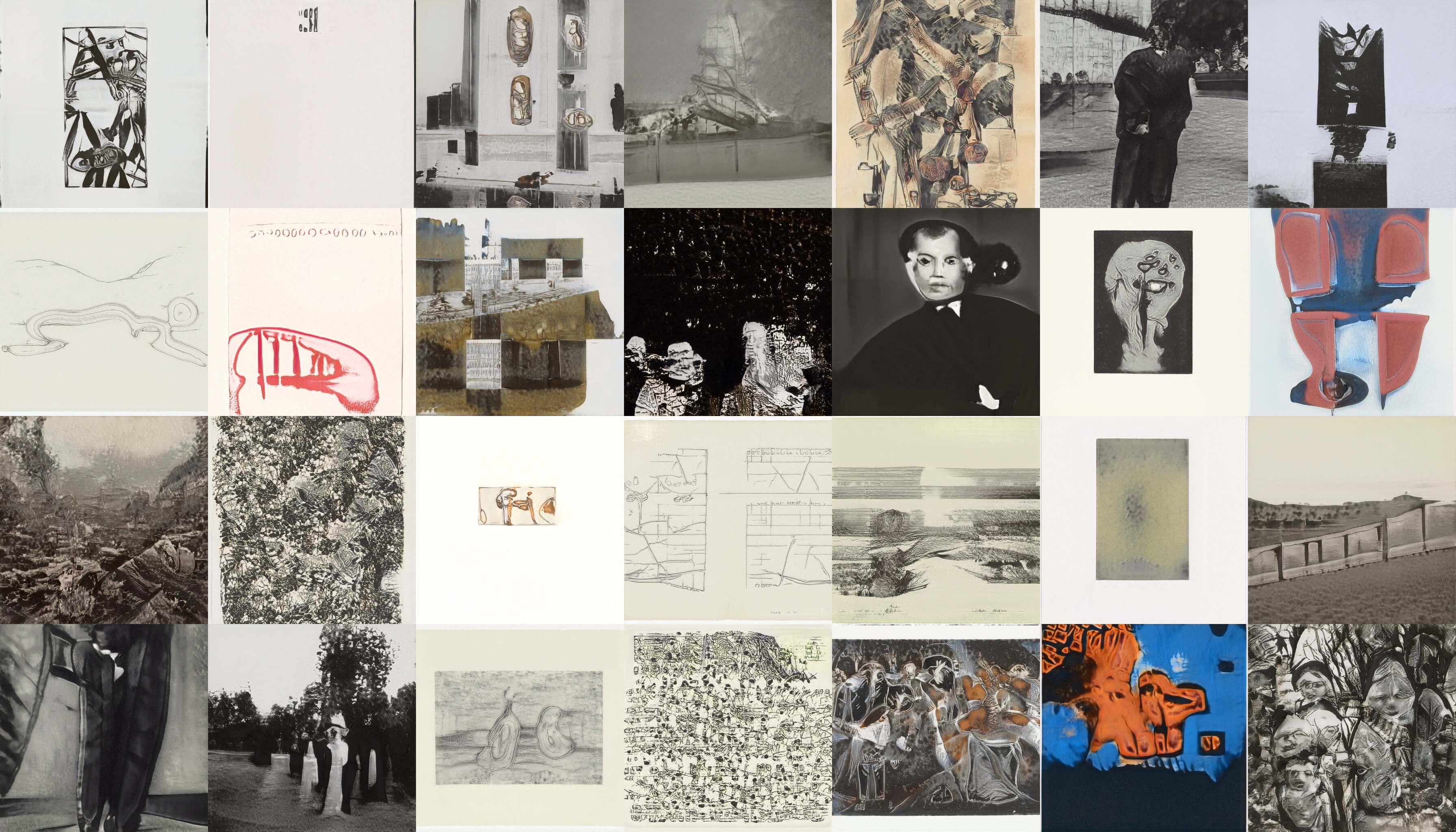

Image credit: GAN trained on 60,000 images from the MoMA (Museum of Modern Art), New York collection

“AI art”, or more precisely art created with neural networks, has recently started to receive broad media coverage in newspapers (New York Times), magazines (The Atlantic), and countless blogs. Combined with the ongoing general “AI hype” and multiple recent museum and gallery exhibitions, this coverage has produced the impression of a new star rising in the art world: that of machine-generated art. It has also led to the popularization of an ever-growing list of philosophical questions surrounding the use of computers for the creation of art.

This brief article provides a pragmatic evaluation of the new genre of AI art from the perspective of art history. It attempts to show that most of the philosophical questions commonly cited as unique issues of AI art have been addressed before with respect to previous iterations of generative art starting in the late 1950s. In other words: while AI art has certainly produced novel and interesting works, from an art historical perspective it is not the revolution as which it is portrayed. Thus, the future of AI art lies not so much in its use for “image making” but in its critical potential in the light of an increasingly industrialized use of artificial intelligence.

The past - computer art

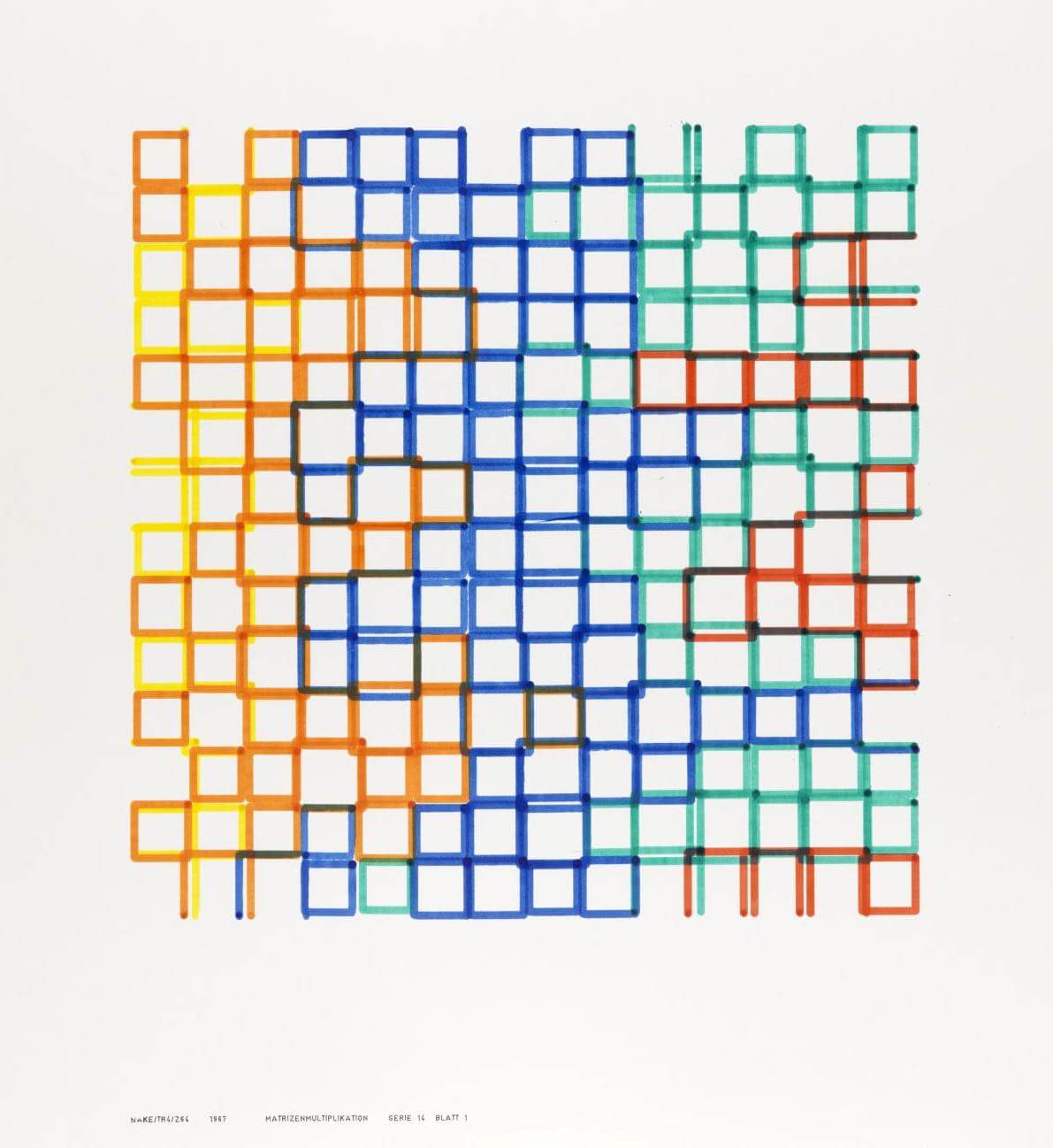

Artists have been using computers to create works since at least the late 1950s, when a group of engineers in Max Bense’s laboratory at the University of Stuttgart started experimenting with computer graphics. Artists like Frieder Nake, Georg Nees, Manfred Mohr, Vera Molnár, and many others explored the use of mainframe computers, plotters, and algorithms for the creation of visually interesting artifacts. What started (as Frieder Nake recalls) simply as an exercise to test some of the novel equipment in Bense’s lab, quickly became an art movement, with Max Bense providing a theoretical framework for it as the logical opposite of fascism1. The literally “calculated” aesthetic of computer art, according to Bense, intentionally avoids all appeal to emotion, and thus makes it immune political abuse.2

While there is certainly no unbroken fifty-year lineage from Frieder Nake’s early experiments with the ZUSE Graphomat plotter to the work of contemporary AI artists such as Helena Sarin one certainly informs the other. In other words, AI art becomes more interesting if we turn to early examples of computer art to understand it. We could go so far to say: early computer art provides the missing theoretical framework for contemporary AI art.

But why choose early computer art as a reference here, and not, for instance, photography, as proposed by Aaron Hertzmann, or film? On the surface, the current development of AI art seems to be similar to the historical development photography and film; they both started as mere “tech demos” (think of the famous steam railway film that supposedly made the audience leave the theater in terror), went through a phase of emulating more traditional media (painting and theater), and eventually became artistic media in their own right. Moreover, photography and film both have a long history as points of reference in the theoretical reflection of machine-facilitated art3. Finally, photography and film have long settled the issue of machine authorship (that I will discuss in detail below): “the owner or operator of the machine owns” the work created with it.

So, photography and film do have relevant lessons to draw for AI art. Computer art, however, is much more specifically and directly related to AI art in this way: like AI artists today, early computer artists were mainly concerned with multitudes of images. Early computer artists understood the algorithmic production of works as the creation of generative aesthetics (plural). Computer art pioneer Frieder Nake talks about this idea in a lucid 2010 interview:

Nake’s argument is simple: there are no masterpieces in computer art because computer art is not about the production of “pieces”. It is about the production of system designs, and about the beauty and coherence of these designs. In other words, it is the method, not the artifact, that is relevant for the aesthetic judgement of a work.4 While, over the course of fifty years, the tools to produce such systems have certainly changed, the idea of “generative aesthetics” has remained.

One of the first artistic applications of machine learning, Alexander Mordvintsev’s DeepDream (2015), for instance, is above everything else a system of visual transformation (technically based on feature visualization). While DeepDream has mostly been used in conjunction with ImageNet/ILSVRC-20125, and has thus produced an overwhelming amount of dogs, it is, as a system, not limited to any particular dataset. In fact, DeepDream could be used to find anything in anything. One could argue that some of the negative reception to DeepDream is a result of not bringing the system to its full potential by using different datasets, and presenting samples from the system as full works without reflecting on their generative nature. Of course, this problem is not unique to AI art but an issue with all of media art, and under market pressure, is bound to persist, as recently demonstrated again by the use of DeepDream as a fashion pattern machine.

If we take some of the most popular works labeled as AI art right now, for instance works by Anna Ridler, Sophia Crespo, Memo Atken, Mario Klingenmann, Gene Cogan, and others, it is immediately obvious that they are about sets of images, too: they are about GAN latent spaces filled to the brink with images, and about finding ways to explore these spaces in a meaningful way. From a more technical perspective, we could say that both early computer graphics and contemporary AI art operate with probability distributions and the exploration of these distributions6.

This is not to say that AI art has not contributed anything new to the history of art – just that the underlying philosophical questions of AI art are historical questions, rather than questions unique to the present moment in art. What, however, defines this present moment in the first place? And what concrete answers does contemporary AI art give to these historical, philosophical questions?

The present - three questions about where we are

Is the AI art gold rush here?

It has been recently proposed that the AI gold rush is finally here. In relation to the extreme media hype surrounding AI in general and neural-net based AI art in particular, however, the presence of AI art in the established art world so far is minimal. AI art, at the present moment, is very much an insider’s game, with a small number of protagonists driving a lot of the aesthetic and critical output. This is not necessarily a bad thing. After all, the very idea of contemporary art once implied independence from large institutions and the market. It is, however, a fact that is conveniently overlooked in popular descriptions of the state of AI art today.

Auctions

The “gold rush” idea, of course, refers mainly to the fact that works branded as “AI art” have recently been sold to collectors. In the most famous example, the french collective Obvious sold a mediocre, gold-framed latent space sample from Robbie Barrat’s portrait GAN for the quite astonishing price of $432.500 at Christie’s. A previous version had been sold to a private collector for a price of $10,000 some weeks prior. This created a massive outrage within the nascent AI art community. While the outrage over the attribution of the sold work is of course justified, it is also the case that both the price and number of works of AI art sold are not indicative of a “gold rush”. Buying AI art, at the moment, is mainly a publicity stunt. Christies got free PR certainly worth an order of magnitude more than the selling price of the french collective’s work it notoriously auctioned.

The Chelsea gallery that put on Ahmed Elgammal’s Faceless Portraits Transcending Time show has, with this, primarily put itself on the map by claiming to show the avant-avant-garde, as bluntly celebrated by the gallery’s owner, Philippe Hoerle-Guggenheim:

Some viewers interpret AI art’s promise as a threat. In his office, Hoerle-Guggenheim showed me a comment on an Instagram post for the show, complaining that the gallery is featuring art created by machines: “What a shame for an art gallery…instead of supporting human beings giving their vibrant vision of our world.” Given the general fears about robots taking human jobs, it’s understandable that some viewers would see an artificial intelligence taking over for visual artists, of all people, as a sacrificial canary. Hoerle-Guggenheim celebrates the criticism — it just demonstrates interest in the show.

Exhibitions

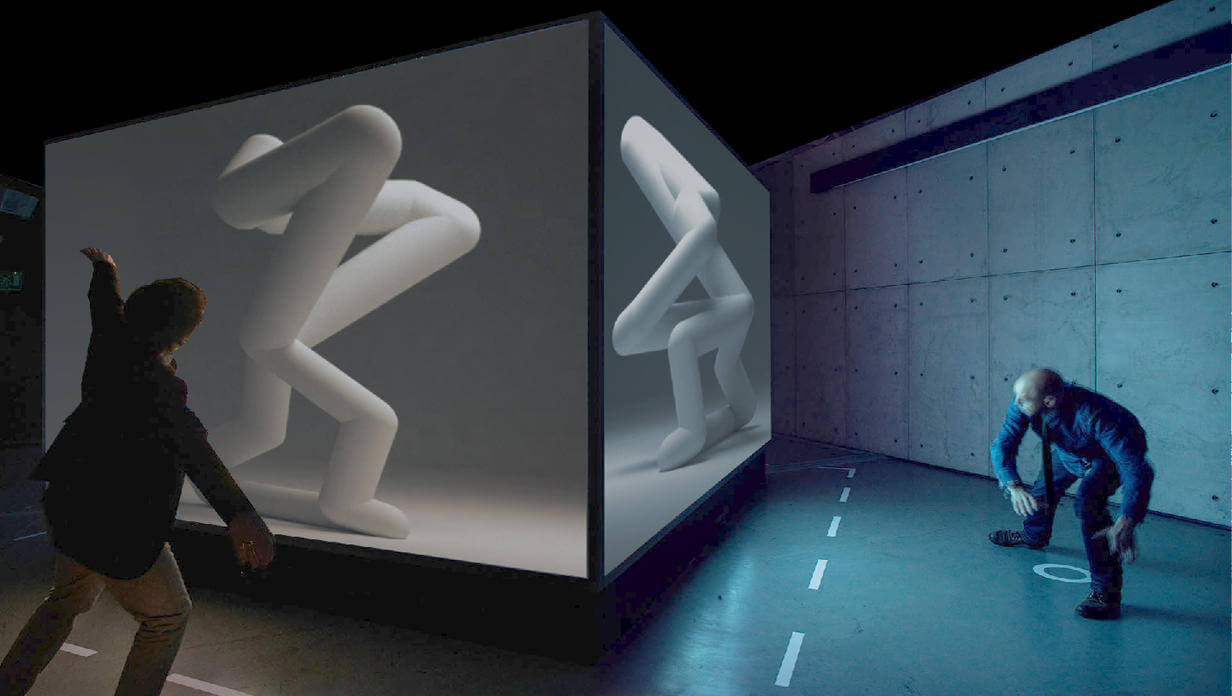

At the same time, AI art shows so far have been almost trade-show like exhibitions of works that use or even just talk about machine learning, broadly defined. The most recent example is the “AI: More Than Human” exhibition at the Barbican in London, which also happily mixes tech demos, purely decorative pieces like TeamLab’s work, and works of AI art.

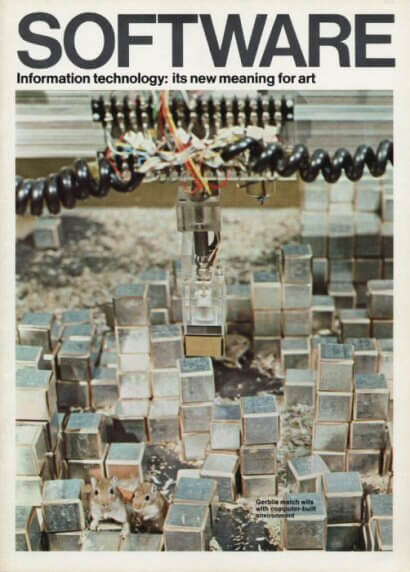

It helps to take another look into the history of computer art to understand this curatorial eclecticism. One of the first exhibitions of technologically informed art, the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition in London (1968), embraced the same non-concept of showing “everything technology”. Like the Barbican show, it claimed to have “discovered” the use of technology for art, despite much earlier examples (like the shows in Zagreb a year earlier and Stuttgart in 1965). Eventually, however, shows like Jack Burnham’s Software exhibitions at the Jewish Museum in New York (1970) began to focus on specific questions resulting from the use of technology, rather than putting it on display as a novelty.

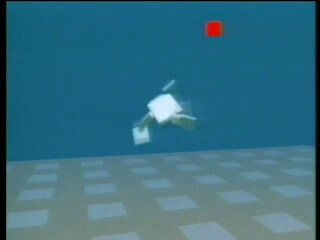

Moreover, historically, tech demos and works of art are points on a continuum that is often retrospectively adjusted. During the height of the so called second wave of media art in the 1990s, as part of a short-lived artificial life craze, explicit tech demos, like Karl Sim’s famous Evolved Virtual Creatures (1994) were part of many exhibitions. At the same time, artists like Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau published articles about their works, like A-Volve (1994) in technical journals, and gave talks at technical conferences like SIGGRAPH.

Both phenomena, the strange generality of AI art exhibitions, and the mix of artworks and tech demos, could thus be regarded as side effects of the art world’s slow adoption of a certain technology. Yet, this adoption is underway, just not branded as AI art, as some recent works by established artists show7.

Does AI art prove that machines can be artists?

In the discussions unfolding after the Christie’s scandal, the question of machine authorship very soon emerged and was gladly adopted by the media and exhibition makers. And indeed, the thought that machines could be artists, could even replace artists like they will replace all other jobs, is just too enticing to not discuss: after all, making art is often seen as the most human of all activities. Almost as popular as the question of whether machines can be artists is its inverse: the idea that AI will finally tell us “what makes us human”, as the Barbican exhibition puts it. Historically, the authorship question has always been the popular interpretation of art made with computers.

Frieder Nake offers a general critique of this line of thinking in regard to the computer art of the 1960s which could easily have been written about AI art:

Progress in the world of pictures today is the same as that in the world of fashionable clothes and cars […] It seems to me that “computer art” is nothing but one of the latest of these fashions, emerging from some accident, blossoming for a while, subject matter for shallow “philosophical” reasoning based on prejudice and misunderstanding as well as euphoric over-estimation, vanishing into nowhere giving room to the next fashion. [… ] Questions like “is a computer creative” or “is a computer an artist” or the like should not be considered serious questions, period. In the light of the problems we are facing at the end of the 20th century, those are irrelevant questions.”

If we think of the “accident” defining AI art as the discovery of GANs, or the development of DeepDream, then the rest of this passage seems eerily fitting.

Finally, if we go back even further, we can argue that the question of machines as artists is as old as computers are. In his famous 1950 paper Computing Machinery and Intelligence, Alan Turing writes about the question of machine creativity:

The view that machines cannot give rise to surprises is due, I believe, to a fallacy to which philosophers and mathematicians are particularly subject. This is the assumption that as soon as a fact is presented to a mind all consequences of that fact spring into the mind simultaneously with it. It is a very useful assumption under many circumstances, but one too easily forgets that it is false. A natural consequence of doing so is that one then assumes that there is no virtue in the mere working out of consequences from data and general principles.

In other words, in Turing’s view the question if machines can be creative is based on the false impression that creativity is independent of the working out of consequences. In Turing’s view, and paraphrasing Adorno, we could say that artists follow an intuitive logic, an intuitive process that nevertheless is as rule-bound as any rational process is. It is thus not the exception that machines are creative, but the norm, and the question “can machines be creative” arises from a flawed notion notion of creativity.

Exactly because it is flawed, the authorship question is almost never promoted by the AI artists themselves. Where it appears, as in the Christie’s auction scandal, it is a pragmatic result of the technological involvement of AI art and its embrace of open source culture: media art and computer art have traditionally not open sourced code/data, and have thus not run into similar problems.

Is AI art “proper” (contemporary) art?

Closely connected to the question of adoption in the art world is the question of critical reception. In a review of the Barbican show, Jonathan Jones wrote in the Guardian about Mario Klingemann’s piece Circuit Training:

It’s one of the most boring works of art I’ve ever experienced. The mutant faces are not meaningful or significant in any way. There’s clearly no more “intelligence” behind them than in a photocopier that accidentally produces “interesting” degradations.

If you watched the interview with Frieder Nake above, this view should sound eerily familiar to the “I don’t really like it!” of the late 1960s. One of the reasons, as pointed out above, is of course the difference of systems and artifacts: Klingemann’s work is certainly more than a mere collection of images that can be judged individually. Nevertheless, Jones’ critique (particularly using the photocopier analogy) aims at one specific issue of AI art: its mimetic quality.

Mimesis is an aesthetic concept that is as old as philosophical aesthetics itself. It describes the aesthetic process as the production of artifacts that mimic reality to a certain degree. Modern art has famously tried to emancipate itself from mimesis by experimenting with abstract images first, and then getting rid of images altogether (in conceptual art, for instance). Contemporary art is not about image making, and has not been about image making for a long time. While this might seem like an entirely flawed development, particularly to those who admire the accomplished craftsmanship of highly mimetic art (like, for instance, Gustave Caillebotte’s work below), it is in fact nothing more than art becoming critically aware that it is a part of a rapidly changing world after the end of the long 19th century.

In contrast, AI art, in the limited scope discussed here, has the problem that it is always essentially mimetic. After all, all of a neural network’s knowledge about the world comes from the data it processes. “Mimetic” here does not imply that, like (non-abstract) photography, AI art is bound to produce artifacts that can be clearly mapped in a one-to-one fashion to the real world. It is, however, limited to the scope of the dataset it operates on. Novelty only happens within this scope. To give a concrete example: a GAN trained on van Gogh painting will certainly produce interesting variations of van-Gogh-like images, but it will never produce an image that, let’s say, reflects on the art historical context of van Gogh’s aesthetics (impressionism). A neural network can never distance itself from the data it operates on, as this data is its entire world, not just one of many subsets of the world, as it is for the human observer.

This is also why the “novelty effect” of artistic demonstrations using machine learning often wears off so quickly. As Zach Lipton has said about MuseNet: it “is uninteresting in precisely the same way as every generic ‘we trained an LSTM to generate __’. I don’t think there is anything here that a musician should find interesting.” Pure mimesis, it turns out, is impressive, but has no lasting aesthetic value. It provides immediate gratification in the easy recognition of similitude, but this quickly wears off. In other words, purely mimetic AI art becomes kitsch fast.

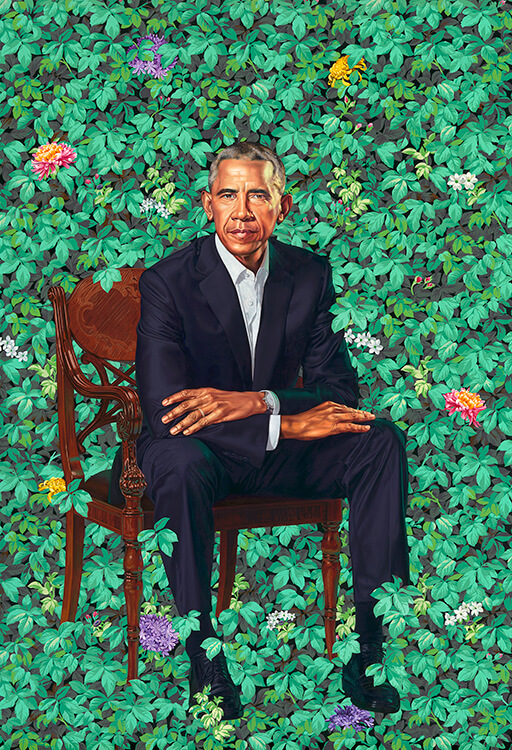

The prominent cases of AI art deals mentioned above fall into this category. Ahmed Elgammal’s pieces are even presented “in elaborate frames” to, “reinforce a connection to the cradle of European art”, as Hoerle-Guggenheim states. Obvious did the same. Both sold what are effectively glitchy versions of historical portraits, a style of work that has not been part of contemporary art for many decades now – except in its dedicated historical reframing of portraits, as in the work of Kehinde Wiley painting “classical, European” portraits of people of color who would never appear in a “European portrait” dataset.

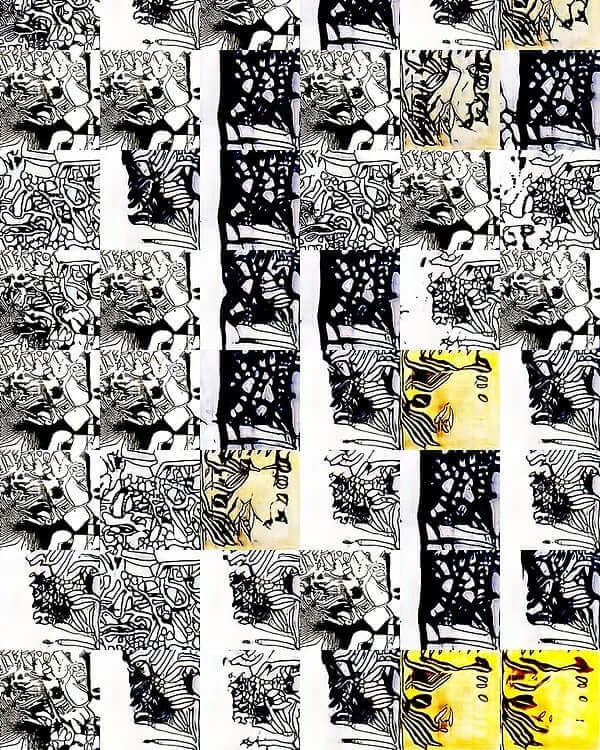

Artists working with AI have realized this, of course, and as a consequence often intentionally work at the mimetic limits of neural networks. The purely abstract GAN-paintings of Helena Sarin, for instance, show that some artists are well aware of these historic implications of their technology of choice. This awareness has a history in computer art itself: Harold Cohen’s Aaron drawing robot, for instance, a multi-decade exploration of pure imitation of style, is the most prominent example of work at the boundaries of the mimetic faculty of machines.

In the work of Helena Sarin we also find one possible cure for the mimetic disease: the hand-curation of datasets. As pointed out before, if DeepDream is future kitsch it is future kitsch because it has not been used to its full potential, i.e. outside of ImageNet/ILSVRC-2012. The more interesting/well-curated the datasets, the more interesting/complex the art. Faces will beget faces, ImageNet will beget dogs, but small, custom datasets (in combination with the right selection of techniques) will lead to interesting results - it is indeed (almost) all about the data at this point, as Sarin herself argued.

The future - the critical potential of AI art

Here’s a prognosis: As soon as GANs have become proper Photoshop filters, a thing we can expect from looking at the work of David Bau and others, the mimetic problem will disappear. At least it will stop being the focus of aesthetic explorations of artificial intelligence, much like art accessing the Internet is not presented as NetArt anymore.

Instead, artists will finally embrace the critical potential of AI art: to use AI to criticize itself, as a technology used in the real world. After all, the power of technologically informed art, as Walter Benjamin puts it in The Author as Producer, is that it can stand in the relationships of production, actively shaping the way a certain technology is used, rather than just providing aesthetic commentary from the sidelines. This future of AI art has already started: one of the most important articles on GAN-generated faces, How to recognize fake AI-generated images was written by an artist working with machine learning, Kyle McDonald.

In other words, AI art will be a driver of innovation but, exactly as proposed by Frieder Nake fifty years ago, not so much a driver of aesthetic innovation but of critical innovation. Just as abstraction is a critique of realism in painting, AI art will become a medium for the critique of “realist” AI, i.e. AI used under the assumption that it is a proper agent in the real world (like ImageNet is problematically assumed to be a valid and exhaustive sample of the real world).

Conclusion

These are exciting times, for science and art alike. We are not, however, in the middle of an artistic revolution, and even less so are artists in danger of being replaced by machines any time soon. It is often overlooked that (non-trivial) art progresses much like science does - by building on a history of invention and discovery, sometimes taking incremental steps, sometimes questioning and overthrowing paradigms. Time will tell if AI art ever becomes a revolution that will question the very way we produce art – but from the history of contemporary art in general, and from the history of computer art in particular, this seems unlikely to happen. Much more likely is the continuation of a process we already see today: the slow and steady recuperation of explicit “AI art” by contemporary art. Machine learning, in other words, will become just another set of tools. And with this, the philosophical speculations will vanish as well.

-

This is often overlooked in the discussion of early computer art, which, on the surface, appears to be as l’art pour l’art as it gets. ↩

-

For more context see this amazing TV discussion from 1970 (unfortunately only available in German), where the contemporary artist Joseph Beuys, one of the founders of the Fluxus art movement and one of the most influential proponents of a politically engaged art, confronts Max Bense. ↩

-

Walter Benjamin famously saw film as a liberating force, and as the only truly contemporary medium, a medium literally using the same advanced technical processes as the industrialized world it was used to record. ↩

-

This also connects both early computer art and contemporary AI art to conceptual art, where, according to Sol LeWitt’s famous quote, “the idea becomes a machine that makes the art”. ↩

-

ImageNet can be regarded as the most important image dataset in machine learning today. Originally created in 2009, it currently consists of over 14 million images of everyday objects, people, and animals, scraped from the Internet by Amazon Mechanical Turk laborers. Most commonly used, however, is a subset of this dataset create for the 2012 ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVCR) that consists of 1,000 classes with 1,500 images each. ↩

-

While early computer art relied on random number generators to produce variations of images, contemporary AI art often relies on artificial neural networks that have internalized the inherent probability distribution of an (image) dataset - the kind and likelihood of (visual) features. ↩

-

Such is the case in Pierre Huyghe’s recent exhibition that takes up the idea of using feature visualization for the analysis of human brain activity. ↩